Picture two people, waking up on an average morning.

Picture two people, waking up on an average morning.

Person A eats breakfast, brushes his teeth, and goes to work. Person B starts to make a cup of coffee on her hot plate (can’t remember the last time she had regular electricity) but suddenly the room shakes—enemy air forces have arrived and they’re bombing. Person A clears some early work from his inbox and decides he’s got time to run out to Starbucks to grab a pumpkin spice latte. Person B shoves her few belongings aside in a rush to her computer, frantically entering in the commands to wipe it clean as a near miss blows out all the windows. A has an important question for a co-worker across the hall, but they’re on a conference call so he sends a terse e-mail instead and spends the rest of the morning waiting impatiently for them to notice it and get back to him. B didn’t have time to tell her superiors she was bugging out, so she sneaks around the CCTV cameras to an alley with a good view of the nearest drop point (luckily, there’s a restaurant dumpster nearby and she’s able to scoop up a few handfuls of leftover eggs) to wait for her contact to happen by. A comes back from lunch to find his computer frozen, so he spends most of the afternoon standing over the IT guy’s shoulder and falling behind on his work. B dozes off around hour five of watching the drop but it starts to snow and the cold wakes her up and shitshitshit, there are fresh footprints—she missed her contact.

I don’t have to ask which of these scenarios more resembles your life; unless you live in Syria or the Crimean Peninsula, it’s almost certainly A. My question is, what would your government have to do for you to willingly give up A in favor of B?

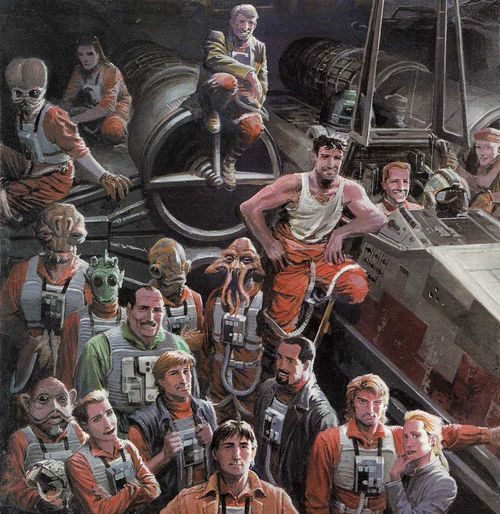

The Expanded Universe of the nineties was all about putting Star Wars fans into the shoes of the rebels, but at the same time, it never really talked about the implications of that—before Shadows of the Empire in 1996, it barely even seemed interested in what the actual Galactic Civil War was like before the Alliance’s ostensible victory at Endor, and even Shadows was more interested (of course) in Luke and Leia than in telling a war story. That was equally true for most of the post-Endor content, and while the war against the Empire technically lasted another fifteen years, most of the time we were seeing it from the perspective of generals, admirals, diplomats, and Jedi. The one major exception (give or take a smattering of West End Games short stories) was the X-Wing series, but while that was a refreshing (and fun as hell) look at the lives of “average” New Republic forces, you couldn’t really call it morally complex—at least no more than the Big Three stories were. The New Republic was by then an establishment of its own, and the closest thing to a sympathetic Imperial in Michael Stackpole’s roster was Soontir Fel, and it’s to the EU’s detriment that he didn’t really have a role in the novels until long after the war had ended.

Even the handful of ex-Imperial characters were rarely if ever glimpsed prior to their defections; there was a flashback here and a cameo there, but we got to know people like Hobbie and Tycho Celchu (and, well, Biggs) as rebels first and foremost, and what they thought about the Empire at the time they were actively serving it didn’t really enter the equation. Joining “the academy” was just something you did—Luke was going to, after all—and anyway, they’re heroes now! Everyone made the right call in the end!

And when you talk about “the heroes” in popular fiction, and certainly in Star Wars, you’re talking about “us”. The New Republic of the EU was made up of audience surrogate after audience surrogate, and naturally it felt good to identify with these people—they were heroes. But for all the Tychos and Hobbies (and Maras, for that matter) who we understood intellectually had once been “bad guys”, we almost never had to see them that way. You could be charitable and say this was reasonable given its focal time period after the movies, but the EU just wasn’t interested in talking about why people had joined the Empire, and when they joined the Rebellion it was depicted as self-evidently, ipso facto, the right thing—because they had won, and wasn’t the galaxy better now?

And when you talk about “the heroes” in popular fiction, and certainly in Star Wars, you’re talking about “us”. The New Republic of the EU was made up of audience surrogate after audience surrogate, and naturally it felt good to identify with these people—they were heroes. But for all the Tychos and Hobbies (and Maras, for that matter) who we understood intellectually had once been “bad guys”, we almost never had to see them that way. You could be charitable and say this was reasonable given its focal time period after the movies, but the EU just wasn’t interested in talking about why people had joined the Empire, and when they joined the Rebellion it was depicted as self-evidently, ipso facto, the right thing—because they had won, and wasn’t the galaxy better now?

The new canon, though—again, largely just because of the realities of the available eras—is building its new New Republic from the ground up. (Fair warning, by the way: I’m going to be discussing a variety of recent spoilers here, from Lost Stars up to this week’s Servants of the Empire finale) We still only have the barest outlines of what the post-Endor governing apparatus looks like, but we have a crapload of protagonists who could yet make up that government. And while there are a handful of true believers like Hera in the mix, they’re more the exception than the rule. Instead, the new canon is all about people who bought in to the Empire, at least for a little while. It’s not just common, it’s basically the theme.

But for every individual who wised up and left the Empire behind, there’s someone who stuck around. For every Thane, there’s a Ciena. For every Zare Leonis, there’s a Chiron. Except that’s not quite correct—for every Zare there would’ve been hundreds of Chirons. One of the things the canon Empire has done best is to show the systems that slowly drain a good person of their individuality and moral center as they rise through the ranks, and while there’s bound to be the occasional Ciena—someone competent who sees the Empire’s evil with clear eyes but convinces themselves it’s better than the alternative—it’s reasonable to believe that the bulk of the command structure is malevolent in a familiar sense, because the more of a dick you are to begin with, the more you’ll thrive within the Empire’s methods.

That’s the command structure, though; the grunts are another story. As we see in Servants of the Empire, the stormtroopers are the first to sacrifice their individuality in the name of the Empire’s mission, but being bludgeoned into obedience is hardly the same as being evil. Yeah, they signed up for it at some point, but remember: so did Biggs and Tycho. The Empire didn’t have a draft; by and large, the average stormtrooper or TIE pilot is just someone who wanted to bring peace to the galaxy, or who needed a direction in life, or in Thane’s case, just wanted to fly cool shit. The Empire’s true evil was in its ability to corrupt these people bit by bit, in doses so tiny most hardly noticed; but corrupted though they were, they were still just people.

So, the Empire wasn’t really that bad because it was made up of average people? No, that it was made up of average people is the worst thing about it. But the stormtroopers weren’t really that average, if only by virtue of being in the military. Even the actual assholes like Aresko and Grint were extraordinary in that regard, if not in a moral sense. The real face of the Empire was Joe Q. Antilles, the civilian who stood by and did nothing, blithely accepting the happy stories Imperial propaganda fed them, because they were too wrapped up in the petty concerns of their day jobs to get involved. Remember Person A, the one we all identified with? That’s the Empire.

Who, then, are the rebels? We’re not living under an evil, tyrannical government, so we have no reason to rebel—but that doesn’t mean we wouldn’t if things were worse, right? True enough, but while you and I may not think so, I promise you there are people in cabins right now, using hot plates and practicing evacuation strategies, waiting for the day the government comes for them. Sure, those people are nuts, but try telling them we’re not living under the Empire.

But it’s not fair to say the only true rebels are the bearded survivalist types; statistically, if our government really did start going bad, plenty of people would be quick to see it and turn against it. So if we’re going to define the spectrum of “realistic” rebelliousness among Imperial citizens, let’s start with good ol’ Tycho Celchu. Tycho’s a swell guy, but as an Alderaanian, he was also a privileged Core Worlder; it’s reasonable to believe he grew up thinking the galaxy was happy and  friendly and full of cute animals, and never had cause to think otherwise until the day he was talking to his family on the comm and suddenly the line went dead. “Alderaan, destroyed?!” he asks. “Celchu out!”

friendly and full of cute animals, and never had cause to think otherwise until the day he was talking to his family on the comm and suddenly the line went dead. “Alderaan, destroyed?!” he asks. “Celchu out!”

For the opposite end of the scale, we’ve got a much, much newer (and canon-er) Alderaanian in the form of Nash Windrider. Nash literally had to sit there and watch Alderaan blow up right in front of him, but instead of leaving the Empire, his support for it shot up to fanatical levels. The only way he could process what had happened without going mad was to lay the blame squarely at the Rebellion’s feet, and to channel every bit of the emotions roiling inside of him into seeing them defeated. Perhaps you think this is silly and illogical, but I hate to break it to you: it is completely not. People are amazing at rationalizing all kinds of bullshit in the name of their peace of mind, and you can never quite tell how they’re going to do so—for instance, as recently as 2011, an opinion poll found that fifteen percent of respondents in the United States, in defiance of all accepted knowledge, still believed that Saddam Hussein was “directly” involved in the 9/11 attacks. These people aren’t evil, and they’re not even stupid, necessarily: they’re just constitutionally incapable of dealing with the reality of what happened. There’s your Nash Windrider.

In an even more recent development, the preview excerpt of Battlefront: Twilight Company includes a revealing scene where the protagonists are preparing to abandon a planet to an impending Imperial surge, and on their way out they stage an unofficial “open recruit” along the local populace in an attempt to replenish their numbers:

“The genuine recruits were a motley assortment of young and old, pampered and desperate. Namir paced among them, watching their eyes, and passed his assessments on to the recruiting officer.

‘Just keep an eye out,’ Namir said. ‘You have to be a special kind of crazy to jump aboard a sinking ship.'”

Namir’s being glib, of course, but not that glib. Leaving a comfortable life behind to join an illegitimate army and rebel violently against the very makeup of one’s society is not a rational act—and no shortage of real-life examples tell us that it’s definitely not a common one; a “rebel” almost by definition is an extraordinary person. In the GFFA’s case, where the thing being rebelled against is unambiguously evil, it’s something that deserves our respect and reverence. Pick a person off the street, meanwhile, and on the Windrider/Celchu Scale, they’re probably somewhere safely in the middle. That doesn’t make them bad, it makes them normal—and I think if there’s one lesson to be found in the new canon so far, it’s that Star Wars fans shouldn’t be too comfortable in our certainty that we’re better than that.

Great article. Between stuff like Lost Stars and Aftermath, the new canon has done a great job at showing what life is like for normal people in the GFFA, and the sacrifice you make to be in the rebellion. Hoping to see that continue!