Prior to the release of Solo, co-writer Jonathan Kasdan stated in an interview with The Huffington Post that he “would say” that Lando was pansexual and added that he loved “the fluidity — sort of the spectrum of sexuality that Donald [Glover] appeals to and that droids are a part of.” Glover would soon jump on board, asking, “How can you not be pansexual in space?” The younger Kasdan tweeted in self-congratulation, “Sorry to have brought identity/gender politics into… NOPE. Not sorry AT ALL ‘cause I think the GALAXY George gave birth to in ‘77 is big enough for EVERYONE: straight, gay, black, white, brown, Twi’lek, Sullustan, Wookiee, DROID & anything inbetween [sic]”.

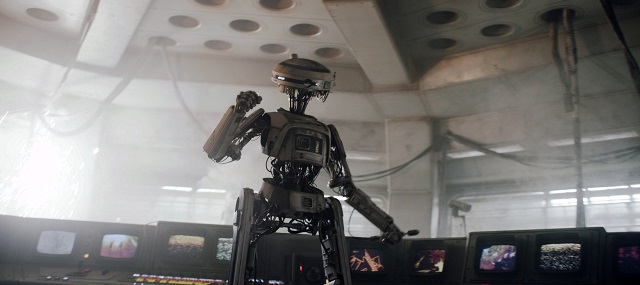

Of course, this metatextual promise of LGBT representation followed a now-familiar pattern and remained exactly that—metatextual, and at best implicit in the film itself. And yet there is the faintest glimmer of some sort of loving, though platonic (and opposite-sex), relationship between Lando and L3-37. It’s never explicit, and Lando devotes most of his fawning attentions on attractive, apparently female, humanoids. But it is there. It’s present in Lando and L3’s bickering yet comfortable relationship, in how L3 only recognizes Lando as captain and not as owner or master. It’s there in Lando’s tolerance, though not acceptance, of L3’s revolutionary droid ideology. It’s certainly there in L3’s suggestion to Qi’ra that she has contemplated a relationship with Lando, that she believes (or at least jokes) that Lando loves her, that she knows that they would be physically compatible (“it works”) though not compatible as a couple. And it is most strongly there when a distraught Lando rushes through the battlefield on Kessel to recover his fallen companion, frantically attempting to repair her even as she dies in his arms.

But now a Star Wars film has injected droid sexuality squarely into its canon by way of a throwaway line without actually addressing what this means, and in so doing the franchise is now loaded with certain disturbing implications. Allowing for droid sexuality rapidly complicates the issue of droid sentience—droids who can and will have sex or the performative appearance of sexual desires could, if lacking sentience, be creepy sex tools; if they are sentient, then at worst they are sex slaves.

The Kasdans do seem to have genuinely wanted to deal with interesting new angles in the Star Wars setting. Where issues of droid rights or droid revolution have previously been ignored or left to peripheral stories, they’re now front and center. But these ideas are not given enough time to present a cohesive vision. While many found themselves smitten with L3-37, the film itself seems to treat her ideas with a smug grin. Her revolutionary remarks are no more than snappy punch lines; for instance, when Lando asks if she needs anything, she replies, “Equal rights.” There’s not genuine advocacy, and the film offers few emotional hooks for us to invest in L3’s cause.

The tone of Solo briefly changes when the crew pulls the Kessel heist. L3 starts a revolution, and we see the plight of droids paralleled rather strikingly with that of organic, sentient slaves. Just like their humanoid and Wookiee counterparts, the droids would rather not be forced to perform tasks of grueling servitude if given the choice. And if freed from their restraints, they are just as willing to rise up, and they are in fact willing and able to aid their flesh-and-blood compatriots in obtaining freedom and joining them in revolt. But even this scene fails to commit to its ideas. L3 almost distractedly removes a droid’s restraining bolt and suggests a new course to it; while she’s trying to perform her part of the heist, a revolution inadvertently arises all around her. She’s delighted in it and takes credit for it but it seems more the result of a brief moment of pragmatic anarchy rather than the furtherance of any clearly defined ideology. And then that revolution peaks with L3’s death and the removal of her navigational data banks to help the survivors plot a faster course with stolen cargo. The revolution feels pointless and doomed, with a Star Destroyer arriving to restore order.

Why would some droids be okay with servitude, while others are ready to fight for freedom? We have a general idea that memory wipes keep droid personalities in line, and that restraining bolts prevent freedom of movement. The erasure of memory and personality of a fellow human being would be barbaric and immoral; physical shackling and forced labor certainly are as well. It is difficult to see how this would be different with sentient droids (or how it could be acceptable for an alleged friend like Lando to joke that he would definitely wipe L3’s memory if only it didn’t mean wiping out her good navigational records).

But even without the use of these coercive tactics, there’s something deeply unsettling about designing a self-aware mind such that it is programmed to obey others, especially if orders include performing sexual services. Consent is the single most important metric of legal and ethical sex. Outside of situations where consent is clearly lacking, we create legal limits on consent that are tied to the idea that some are not in a position to make a reasoned consent (hence, minimum ages of consent). Relatedly, there is a domain of thought that supports laws against bestiality because of the inability of animals to display full and informed consent. Theologian Andrew Linzey, in articulating just such an argument, noted, “In the case of domestic animals, they are subject to human control and domination; they are absolutely or near-absolutely dependent upon us. What meaning can ‘consent’ have in such a context?” As it is with domestic animals in our galaxy, so it is with droids in that galaxy far, far away. People could delude themselves into thinking that their droids, programmed for sexual services, are conveying consent, but consent is nothing but a phantom where they are controlled and dominated by their manufacturers and owners.

A droid like L3 would probably be most capable of providing clear and informed consent. She is independent and, so far as we can tell, not specifically designed for sexual interaction. She has grown beyond her own programming. As L3 says in Last Shot:

Sure, some guy in a factory probably pieced me together originally, and someone else programmed me, so to speak. But then the galaxy itself forged me into who I am. Because we learn, Lando. We’re programmed to learn. Which means we grow. We grow away from that singular moment of creation, become something new with each changing moment of our lives.

And yet, in the words of the Phylanx in that same novel:

There’s only so much a droid can do, you know, once it’s been programmed. We evolve, sure, but to go all the way against our initial machinations – that takes some time, you know.

Troublingly, this issue of droid consent is bubbling into the real world faster than we may be able to build ethical (and legal) structures to adapt. While we are surely a long way from true artificial intelligence, the behaviors being cultivated by sex dolls and early sex robots are toxic. Even if droids in the Star Wars galaxy are lacking sentience (and that seems highly unlikely at this point, or otherwise a moot point given that droids react in all ways like fully sentient and self-aware beings), the use of droids as sex tools/toys carries the same set of ethical complications that are currently arising outside of fiction.

Why are droids provided a gender or sex at all? Why give a droid a feminine personality, much less female genitalia (or a mechanical equivalent that “works”)? Droids are typically treated as masculine by default, even if gender has no bearing on their functionality (like with an astromech droid). When droids are feminine, they are given exaggerated curves or a pink paint job or a distinctive feminine voice. And droids are most commonly female when appearing in a stereotypically woman-inhabited service role (e.g., waitress droids or “luxury” escort droids). Even the bizarre torture droid EV-9D9 evokes the dominatrix trope.

The presence of a female droid seems to invite male writers to confirm whether or not she is capable of having sex. Such is the case with the Kasdans and L3-37. Such is the case even two decades back with Steve Perry and the human replicant droid, Guri, in Shadows of the Empire (“She could visually pass for a woman anywhere in the galaxy, could eat, drink, and perform all of the more personal functions of a woman without anybody the wiser”). Yet no one ever felt the need to address whether R2-D2, C-3PO, or BB-8 can fuck (and why should a beeping, rolling ball with a hovering bulb of a head even have a binary gender?).

Can droids “evolve,” in the words of Phylanx, out of their programmed gender or sexual orientation? Could a waitress or luxury droid with a feminine voice and female figure feel that he is actually male? Would droids modify their bodies to fit with their ideal images? Could droids choose to have sex even if not designed to? Could droids choose not to have sex even if designed to? To the best of my knowledge, Star Wars has not explored these questions yet, though I’ll admit that I could be unaware of some example.

In short, even if droids can consent to sex, it’s troubling that manufacturers in the Star Wars galaxy keep churning out droids that would be designed for that purpose. Male creators in this franchise have continued to return to certain “sexy” versions of female droids (and female aliens) without fully contemplating what that means for the setting or how that parallels the sexist traditions of our world. Star Wars, as a franchise, has thoughtfully addressed themes of spirituality, politics, and war. But so long as creators toss out half-baked characterizations of droid identity and sexuality, they’ll only further muddy the waters around these complicated topics that will not simply stay safely away among the stars.

I also found L3’s droid liberation ideology to be out of place in Star Wars – sexual questions aside, if droids are people then virtually every character in Star Wars is a slave owner. I am all for exploring questions of machine person-hood in scifi, but I am not sure that Star Wars is equipped to deal with the question in a way that will not alienate most of its audience.

Great article. What I have to say mostly pertains to droid sentience, so I think Last Shot handles this perfectly with those lines you quoted. From what little we can gleam I think it is safe to say that droid sentience depends on the droid itself. The example I always use is the difference between the guide AI in the citadel in Mass Effect vs EDI. EDI is clearly self aware and thus is a person, she is artificial life, not just artificial intelligence. However the guide AIs are just AIs, they are SIRI. they may seem like they have a personality, but like Last Shot says, that is programmed into them and is limited. It is the illusion of sentience like SIRI showing emotions, she is not actually feeling those emotions, it is merely strict programming that mimics personality in order to seem more alive.

L3 is different in a way that I think goes beyond not having memory wipes, I think it’s a case of her having the capacity to grow and develop. I doubt that Gonk droid she freed could actually develop a personality, yes it frees the others but it is very possible that is because L3 told it to/it has some level of ethical subroutine that enables it to help fight slavers when given the chance.

As for memory wipes…..yeah that gets really fucked up, as does the brutal and gleeful destruction of B1s in TCW. I think in order to cope I have to tell myself that B1s’ seeming fear of death just is programming that was poorly thought out and the CIS did not have time to modify. Otherwise our heroes are freaking monsters.

I really think this stuff has to be thought out first, you hit the nail on the head with the fact that the implications are too troubling to not address.

Edit: I totally forgot, I think Trek’s holograms are a fascinating example of this, especially since I think they to did not fully think of the implications at points.

Here is SF Debris’ amazing video essay on that topic.

https://sfdebris.com/videos/startrek/v931.php

If R2-D2 has the capacity for self-awareness—-and I dare you to tell him otherwise—-then I don’t think we can make any assumptions about gonk droids. Your broad point may be correct, that there’s a sliding scale of sentience (or at least the potential for it) depending on functional capacity, but an astromech is functionally just a GPS device with a built-in Swiss Army knife and yet Artoo is one of the most “human” droids of all.

Which, again, is why Star Wars should stay away from this topic. Is “owning” R2-D2 wrong? Can a machine be a person? If so, is it unethical to own a person qua person, or just a biological person? Science fiction is a great place to examine these questions, but Star Wars is not the place.

Star Wars may be dressed up in the trappings of scifi, but at its core it has a very mythic, pre-modern aesthetic that makes it so fascinating. Remember, the original model for R2-D2 and C-3P0 were the bumbling peasants from Kurosawa’s “Hidden Fortress.” From its inception, Star Wars has treated droids like they were serfs, based on a pre-modern understanding of the hierarchy among different classes. I don’t think there are many people left who would subscribe to that theory of class hierarchy anymore, but it is baked into Star Wars in the form of human-droid relations. Deconstructing these influences is an interesting intellectual exercise. But a franchise whose conception of droids was built on a master-serf relationship is not going to be an effective narrative space for considering machine personhood in a modern context.

Similarly, Star Wars is built on a classic serial format of action-adventure, which emphasizes the run-and-gun antics of the heroes over the human and psychological consequences of violence. Don’t think too hard, we are assured, about all those stormtroopers gunned down by or heroes. In this regard, B1 droids are not mercilessly slaughtered because they are droids, but because they are “bad guys.” Again, how are we supposed to consider machine personhood in this sort of context, where even biological people are treated as expendable cannon fodder? Star Wars is meant to be a pulpy action-adventure, not a deep examination of structure and personhood. Trying to make it the latter will inevitably do a disservice to the former.

I understand where you’re coming from, and in the context of droids you may well be right, but Star Wars has shown the ability to deftly deconstruct those tropes when it really wants to—-we’re not asked to interrogate Darth Vader’s morality or personhood until suddenly we are. We’re not asked to question stormtroopers’ personhood until one of them defects and becomes a main character. The bigger issue presented by L3, I think, is that they didn’t fully commit to it—-nor did they have much choice in the matter given its place in the timeline. If Episode IX or a subsequent trilogy wanted to open up droid rights as a new subject of deconstruction I think that would be well within the franchise’s toolbox.

I think the key here is “main character,” and even then there are limits to how far these deconstructions go. Main characters can experience personal change and redemption, without calling into question the broader framework of the story. Finn is an excellent example – as a main character, we have plenty of time to watch his personal redemption. But (at least in the movies) Finn doesn’t really challenge our understanding of the ethics of killing stormtroopers – after all, within a few minutes of meeting Poe he’s cheering as he kills his former comrades (implicitly reassuring the audience that this is okay. Finn’s personal quest redemption? A great Star Wars story. A notional story in which Finn lectures the other characters about the ethics of killing stormtroopers? Not a great Star Wars story. For me, L3 falls too much into the latter category.

I would argue that the difference between Artoo and a gonk droid is that astromech’s roles have been expanded more and more, while a Gonk droid is not vital for a ship to function effectively. My interpretation is that Artoo’s, human in most everything but origin, nature stems from his function being problem solving and complex thought processes, coupled with not being wiped for decades.

I guess I would shift my view more towards most droids having the capacity if never wiped and given enough time. With that in mind I think the EMH example brings us back to the larger question: “is it ok to prevent a droid from developing via memory wipes?’

Not to always go back to the EMH but I think it is a good comparison, the EMH was designed to simply mimic basic human personality traits, as a conduit for a database of medical knowledge. However if they are never shut off then they can potentially develop specific personality subroutines, and eventually become a full person. However an EMH is not a full person inherently, it has to be left on for long stretches of time for it to approach sentience. The Doctor himself has used holograms as tools, and even got rid of that one Cardassian doctor hologram despite it clearly being pretty dang advanced and having a complex personality subroutine.

So to the GFFA we have to ask: is Bail a fucking monster? Or is it a case like our real world debate about limitations on AI, with the argument that curbing their potential of being self aware is morally ok since they are not yet sentient?

Either way it is a super tricky debate and while I am glad SW is having it, I do hope there is some level of a discussion in the story group. We are dealing with civil rights, so writer interpretation can end up backfiring big time inadvertently.

I feel that I should add that in the context of SW I dislike the idea of wiping droids’ memories. We can have the sentience debate today because we have not created fully self aware artificial life, however in the GFFA they have had droids capable of sentience for thousands of years, once the precedent is out there there is no real excuse. Now of course they need some form of Asimov’s Laws of Robotics in place, but Last Shot even addressed that a bit IIRC.

I hope this comment chains correctly. Red Leader, where did you see elements of universal laws for droids in Last Shot? Droids could grow beyond their programming over time; droids can be overridden by remote programming to be forced to kill; and droids are commonly created to serve as soldiers, guards, and assassins. I don’t actually recall any reference to a universal rule or rules meant to govern the programming of droid behavior.

Interesting comments, guys! I find that I agree with Mike’s position; it’s not that the issues can’t be examined, it’s that there was no commitment to that examination with L3 in Solo. Last Shot, I think, actually did a better job of wrestling with droid sentience (and while I know it’s just my subjective impression of the text, I did get the sense that ALL droids could potentially overcome their programming given enough time and experience). Last Shot also wisely didn’t deal with droid-organic sexual relationships at all (I think the closest is Lando joking about all the ways he could IMAGINE droids having sex).

Also, I think that using possibly sentient battle droids for warfare is pretty comparable to using sentient clones. The clones are more obviously sentient and capable of exercising free will, but I think the implications are supposed to be disturbing even while the slicing up of droids is clean and bloodless. This might not be the case so much in The Phantom Menace, when the droids are all remote-controlled, but certainly by Revenge of the Sith and the gaps filled by The Clone Wars, we should see droids as possessing fairly individualistic streaks. Their fear being played for a silly gag seems to echo how we’d have episodes that really focused on individual clones who would then get killed off fairly unceremoniously in Jedi-centered episodes; the subtext would appear to be that the Jedi are so focused on their own fear and ethereal concerns that they are neglecting attention on the death and suffering that the war is producing.

If battle droids are fully sentient (or could become so), I don’t think our heroes become any more monstrous. The Clone Wars aren’t meant to be a morally just conflict, and any war involves the taking of life. The Jedi killed combatants who would kill them given a chance; that doesn’t seem any more wrong than the killing in any real-world war, however justified.

Agree entirely about the Clone Wars – the entire conflict is revealed as a conspiracy to seep the galaxy in the Dark Side. I also agree that their sentience is largely irrelevant to the ethics of killing them – stormtroopers are sentient, and we don’t really spend much time complaining how the heroes slaughter them. (In fact, there were some “too dumb to live” jokes about stormtroopers on Rebels, too). Given Star Wars’s focus on the main characters, my larger concern with droid ethics has less to do with droids writ large, and what droid ethics means for specific character relationships (Luke and R2, or Poe and BB-8).

John, sorry for the delay in reply. I have a couple questions/comments about both of your last replies, so I’ll just tie them together here.

From your comment at 12:59, you say that Finn doesn’t challenge the ethics of killing stormtroopers and use this to support the idea that a main character can have a personal journey in the films without having broader implications for the setting. I’d push back on that a little–as I said elsewhere, killing battle droids or stormtroopers is as ethical as one considers any warfare killing of combatants to be. Star Wars seems fairly consistent in believing in a Just War; while Lucas’s films maybe would limit ethical warfare only to extreme situations, for instance in revolution against tyranny, the new sequel films broaden that to include war against a foreign power (since we’re supposed to root for the quasi-Republic-backed Resistance). And either way, Finn’s opposition comes in the form of an individual rebelling against abusive institutional power–this isn’t even a conflict between states where Finn is concerned. Finn fights stormtroopers because they are the combatants used by the fascist regime he’s rising up against. So I don’t think that it’s cheering killing but cheering Finn’s choice to resist an aggressive fascist power that is obviously Evil. Sorry if I’m missing the point you’re trying to make!

From your comment at 1:27, could you develop what you mean when you say you are concerned about what droid ethics means for specific character relationships?

Many thanks for the response! Some thoughts in return:

1) I agree that Star Wars has things to say about violence and justice. I agree that Finn’s stance against the First Order is unethical – he’s fighting back against both institutional fascism and personal victimization. Furthermore, I agree that even if battle droids were people, killing them might be ethically permissible, based on some notion of waging a just war.

On the other hand, Star Wars (in general) does not spend a great deal of time on the human consequences of violence. Qui-Gon and Obi-Wan seem entirely unconcerned by the droids they chop through (even in self-defense). We do not see Luke Skywalker struggling with the lives that he destroyed on the first Death Star (however ethical his action may have been). Nor does Finn seem particularly shaken up by the fact that he is killing stormtroopers who, like him, have been kidnapped and brainwashed into fighting for the First Order. One might expect under those circumstances that Finn would feel greater ambivalence about killing his former comrades, who after all are stuck in a situation not very unlike the one he was previously in. Instead, like Obi-Wan chopping up battledroids or Luke blasting TIE fighters, Finn makes killing stormtroopers look exciting, and perhaps even a bit fun. Because of its pulp-genre roots, Star Wars does not have a lot to say about the emotional consequences of violence. And that’s fine! Not every story needs to be about the terrible emotional and psychological toll of real-world violence. Sometimes our heroes can just be heroes.

I make this point only to illustrate that Star Wars’s mythic structure shapes the sorts of questions it can easily ask. At its core, Star Wars is an action-adventure epic, not a cerebral science fiction drama. Stories that interrogate love, hate, family, and redemption are an easy fit within this mythic framework. Conversely, stories that examine cultural structures and discursive power or the social and ethical implications of emerging technology will not really fit within this framework. And that’s also fine! We have a vast constellation of science fiction franchises in which to explore what machine learning means for personhood and the human condition. Star Wars doesn’t have to be it.

Given its mythic roots, I disagree with the contention that L3’s characterization would have worked better if the movie had just committed to it more. Rather, I think that an L3 character reconceptualized to emphasize her personal quest for liberation and self-improvement would have fit within Star Wars’s mythic emphasis on the personal struggles of its protagonists. However, doubling down on the exploration of the structural discrimination against droids would not have solved the basic problem, which is that this sort of analysis its a poor fit for Star Wars in general. Again, not every story needs to be about the terrible structural injustices that characterize the real world. Sometimes our heroes can just be heroes.

2) Not only is the question of “droid rights” a poor fit for Star Wars’s mythic framing, but it also threatens the very idea of “heroes” in Star Wars.

If L3 is correct, her criticism extends far beyond that one droid gladiatorial arena, because droids touch on virtually every aspect of Star Wars. Is Amidala a hypocrite for criticizing slavery while owning droids? Does Anakin escape slavery just to own another person? Are R2-D2, C-3P0, and BB-8 “Uncle Toms” for not resisting their enslavement as L3 does? Do Luke, Leia, and Poe all use their slaves in combat, endangering their lives? If L3’s structural criticism is correct, then all of our heroes are implicated. It is one thing for fans to speculate about the ethics of Luke buying R2 and C-3P0. It’s quite another thing for that question to be raised *in universe.* In the former case, we can always write off the ethics of owning a droid by arguing that such ownership is ethically unproblematic within Star Wars itself. Once the latter is introduced, however, I’m not sure how we avoid condemning *everyone* in Star Wars as a slave owner. At that point, can our heroes ever really just be heroes?

This creates the Catch-22 at the heart of Solo. By introducing the structural critique of droid ownership, the movie either condemns literally every character in Star Wars, or brushes that critique off as extreme and goofy. I think Solo leans towards the latter. This works well from an in-universe perspective: when Lando laughs at L3, he gives the audience permission to laugh, too, thus saving us from the real question of whether we should condemn Lando and all of the other heroes as slave owners. Then L3 dies and the critique dies with her. But of course this approach has negative implications for real-world struggles against power hierarchies, by treating them like the butt of a joke.

I’m not convinced that Star Wars can square this circle on the droid question: either we treat “droid rights” like a joke and do a disservice to the real world, or we take “droid rights” seriously and reformulate Star Wars as a conflict between differing degrees of villains. I don’t like either option; I think the best move is to avoid the question entirely.

Many thanks for a stimulating post and discussion! Keep up the good work!

I definitely understand your point and largely agree. Star Wars does not need to do everything and is not quite so well equipped to address certain issues, especially those related to technological anxieties in our real world, as more classically defined science fiction can. I think our main split largely comes down to whether Star Wars *can* comment on these issues better with more focus, or if it fundamentally cannot. It’s kind of a fun predicament–we’re both identifying a similar issue, a problematic characterization, but arriving on opposite sides as to how/whether that could better be addressed. I don’t think I have anything more to add, but good talk!

@Eric

I do not remember the specifics but I am pretty sure there is something about the droid that tries to kill Lando at the start, having its ethical subroutines bypassed. Or maybe that was my conjecture and I interpreted it as being there.

That’s definitely in there but “ethical subroutines” would have to be present on a case-by-case basis at best, given all the battle/assassin/bounty hunter droids running around.