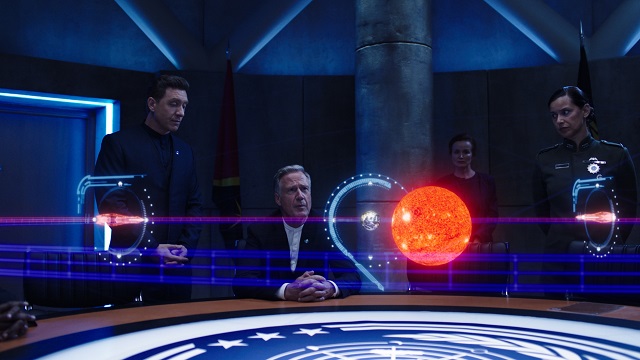

Last week saw the conclusion of the third season of the acclaimed science fiction television series The Expanse. Adapted from the novels by James S.A. Corey (of SWEARHAT fame!), The Expanse follows the crew of the stolen warship Rocinante as they’re pushed and pulled between the far-future solar system’s major political powers and an encroaching and poorly-understood alien presence.

I’m a late convert to the show myself, having streamed the first two seasons on Amazon just in time for the third’s debut this past spring on SyFy—where it would soon be canceled, the bastards. Luckily, Amazon chose to pick up Rocinante‘s reins and continue the series, meaning that in a year or so the show will return to where my journey with it first began. And there’s plenty more to come, if the source material is any indication: the series is slated to conclude with the release of the ninth novel next year, so if the show sticks to a one-book-per-season pace (though that’s varied a bit already), that means six more seasons!

Nine seasons of television are a hell of a time commitment, and for me at least, nine novels even more so—but at the moment I have every intention of sticking around, and once the show is over I plan to spend six months or so reading the novels. What makes The Expanse so compelling, and what qualifies it for precious column inches here on a Star Wars blog? Let’s discuss.

Politics is personal

The prequel trilogy is infamous for, among other things, kicking its story off with the phrase “taxation of trade routes”—current events notwithstanding, how could you expect modern audiences to get invested in a trade war when they came for laser swords and spaceships? The lesson many learned from that era (one that, frankly, the newer films have done very little to contradict) was that politics is too complicated and too dry for Star Wars filmmaking, and better off avoided.

But the truth is, Star Wars was always about politics. Where the prequels assumed a galactic-scale, operatic perspective, the original trilogy distilled its political context into a handful of individuals: a politician fighting the oppressive government from her position of privilege, a poor farmboy whose only option to escape his hometown is to enlist in said government, a smuggler living in the system’s corrupt cracks, and a scoundrel trying to live respectably in that same corrupt system without losing his soul. In the prequel trilogy the characters debated policy; in the originals they embodied it.

The Expanse leans on the latter approach, but still manages to live in both worlds—the powerful and the average. One of the main characters is Chrisjen Avasarala, a high-ranking United Nations official (they basically run Earth now). For the first season or so she barely leaves the building, let alone Earth, but her struggles—with her superiors and competitors within the UN as well as with hostile powers on Mars and among the outer planets—are always tied directly to the life-or-death stakes faced by the Roci‘s crew, as captain James Holden’s more personal mission repeatedly intersects with Avasarala’s interests.

And it goes both ways: in the second season (vague spoilers ahead) the actions of Holden’s cohort, one miserable sonuvabitch in particular, avert a major disaster on Earth, with Avasarala looking on helplessly. Nobody is all-powerful or all-seeing in this story, everyone has skin in the game—and every moment of victory stems from individuals choosing to do the right thing, on both personal and planetary levels. The world of The Expanse may not have the Force, but it deals extensively with the next best thing: simple human decency.

The sequel trilogy shares the originals’ focus on (relatively) ground-level perspectives—Finn’s naïveté gives us a sense of what life is like within the First Order, Poe and Rose are the idealistic everypersons of the Resistance, and Rey is, well, nobody. But Finn and Poe aren’t really representative of their respective systems, are they? Finn could well be the only First Order soldier in decades to defect, but he’s definitely the only one we know anything about, so who’s to say? Later, Poe is our entrance point into a serious internal conflict among the Resistance’s ranks (one Finn and Rose are happy to contribute to), but because we don’t get to know anyone on the other side—even its leader, Holdo, is deliberately kept at arm’s length—his mutiny feels much more like a popular uprising than the ten or so people it really is, and Holdo’s seeming lack of reason, while intentional, comes across to many as borderline manipulative instead of organic and justifiable. Both Finn and Poe’s choices imply some interesting complexity within their respective ranks but the films deny us their larger context, and instead both characters’ unorthodox actions seem to happen in a vacuum.

“Science” is not a four-letter word

Scientific accuracy is not necessary in Star Wars, or even important at all. As long as everything operates under consistent rules, ships in space can bank, make noise, have variable gravity, and so on. But just because something isn’t necessary doesn’t mean it can’t be a useful tool for storytelling. Recently we’ve seen two high-profile instances of characters being sucked out into space and barely surviving—but Star Wars space doesn’t work like real space, so why choose to make a big deal about that? Because real space is dangerous as hell, and danger is exciting!

The Expanse has a lot of great selling points, but one SyFy particularly enjoyed promoting was its frequent use of plausible space physics. One of the first things we see in the show is a Belter—people who have lived in the solar system’s asteroid belt for generations—who can barely live within Earth’s gravity. Later we see a sparrow on the asteroid Ceres cruising around like a hummingbird. But those are just texture: the meat and potatoes of The Expanse‘s storytelling is space combat, and only-slightly-less-intense space travel. Ships can get from planet to planet in a reasonable amount of time, but if you’re running for your life? That kind of acceleration can be just as dangerous as the people shooting at you. Getting up to a certain speed requires travelers to strap themselves down and inject a special cocktail to keep themselves both conscious and solid. It’s familiar, ubiquitous technology, but it’s never taken for granted, and in some cases you’re better off just sticking around to fight.

There are plenty of other ways for space to kill you, too. Equipment needs to be secured just like people do, and a loose toolbox can become a cloud of comically-shaped projectiles, capable of puncturing your space suit or just clean taking your head off. As we find out late in the third season, sudden deceleration can kill you just as badly as acceleration, and even if you survive, there’s no gravity to drain the blood out of your lungs. Forget aliens—the real villain of The Expanse is physics.

Don’t get me wrong, all in all this kind of stuff would be a little graphic for Star Wars. Even Rogue One seemed reluctant to show its human heroes dying in any way other than big, bloodless explosions (those randos who stumbled upon Darth Vader, on the other hand…). But that doesn’t mean they can’t play with this, ahem, toolbox a little more. Inertial compensators and repulsor gravity mean that traveling on the Millennium Falcon is rarely more intense than being on a Cessna in bad weather, but surely one of those systems is bound to fail eventually? Imagine if one of the hits the Falcon took during the Kessel Run knocked out the gravity and Beckett had to inject coaxium into the engines while floating, just to add a little extra novelty. Honestly, it’s kind of insane that with all the stuff that’s gone wrong on the Falcon over the years we’ve never seen it lose gravity—where’s the fun in that?

Or they could think bigger. The Akkadese Maelstrom in Solo was a great introduction to abnormal space environments, but I’d love to see a big-screen supernova or a nebula sometime. [1]Admittedly, Star Wars Rebels was great at this. Or even some variations in planetary gravity—look at the insane variety of environments created for Revenge of the Sith, then consider that every single one of them seems to have normal gravity, and Polis Massa aside, normal oxygen levels. We see alien species wearing breath masks all the time; why not have our human heroes visit, say, the Kel Dor home planet, and deal with the attendant drama of surviving there for a while? Relatedly, imagine if the Ugnaughts were conceived as having evolved on Bespin. You could go low and design a super-tough species adapted to the extreme gravity of the gas giant’s surface, or go high and give them wings. It doesn’t have to make perfect sense, but a little consideration of “why do these aliens look like this?” would go a long way.

Culture over caricature

Speaking of aliens, Star Wars is famous for the fantastic diversity seen in places like the Mos Eisley cantina and Maz’s castle. But part of what makes those locations possible is those beings’ commonalities—you may be an elephant man or a demon or a hand puppet but sometimes you just want a relaxing drink like anyone else. That’s great up to a point, but in the rare event that we actually get to know any aliens, the result is characters that feel, well, pretty familiar. Joonas Suotamo could play Chewbacca as himself speaking Finnish and very little else would have to change. Jar Jar can breathe underwater, but give him a rebreather in one or two scenes and he could just as easily have been Ahmed Best.

The Expanse doesn’t even have alien characters (at least not yet), but it features three human cultures that couldn’t be more distinct. The UN is a multicultural entity unto itself, but as the ruling power of Earth it feels very much like a combination of the real UN and the American executive branch in terms of its espoused ideals and internal divisions. The citizens of Earth feel equally familiar, but with just enough new details to show that society has evolved—one prominent religious leader is a woman in an interracial same-sex marriage and it’s never so much as blinked at, and our hero James Holden is the only child of a genetic collective, meaning he has eight biological parents. [2]Holden was designed, quite literally, to carry on his parents’ fight to preserve their undeveloped land in the face of population restrictions—remember what I said about characters … Continue reading

Then we have the Martian Congressional Republic, the system’s much more aggressive superpower. Their planet’s still in the process of being terraformed, and life remains hard enough that they’ve got a bit of a complex about how comparatively pleasant Earth is. The day-by-day fight to live on Mars at all evolved into a zealous assertiveness that extends from their commanding officers to their ubiquitous marines, and calls to mind the chest-thumping militarism of Star Trek’s Klingons (though it’s worth noting that my favorite character, the Rocinante‘s pilot Alex Kamal, is a Martian who also happens to be the most laid-back member of the crew—subverting stereotypes is important too).

Last but far from least, out past Mars we find the Belters. Known formally as the Outer Planets Alliance (though they’re not big on formality), the Belters are hands-down the centerpiece of The Expanse‘s cultural landscape. While Earthers and Martians (“Inners”, as they’re called in the belt) display an admirable range of ethnicities and accents, Belters have been removed from the rest of human society for so long that they’ve developed a unique creole of their own—one that waxes and wanes even within Belter environments, depending on how metropolitan any given station is. Like many emigrants, their forebears wouldn’t have traveled that far out unless they really needed the work, and thus Belters are the real blue-collar rebels of the system; where Martian independence revolves around the state, Belters are a loose confederation of individual actors at the best of times, a motley assortment of pirates and daredevils at the worst.

It’s from all three of these cultures that the Roci draws its crew, and while their unique situation goes a long way to carving them out as individuals, the conflicting temperaments (and loyalties) of their home powers are never far from mind. We spend two and a half seasons getting to know Naomi Nagata, the Roci‘s Belter, but (vague spoilers again) only once she spends a good chunk of time with other Belters do we realize how much we didn’t know, how much she was suppressing to fit in with the others. Every character has a context, and even when we don’t see it it’s still working under the surface, coloring their actions and attitudes, even their voice.

This is something almost never addressed in Star Wars, particularly the films. At best, we meet a single character and then the supplemental material extrapolates their species’ society from that one person’s personality and/or career choices. Chewbacca is Han’s sidekick, ergo Wookiees carry life debts—I actually appreciate that Solo undercut this a bit by not making a big thing out of Han’s roundabout liberation of Chewie; their partnership is ultimately one of choice, not cultural necessity. But absent that, what exactly is Wookiee culture like? What kind of government does Kashyyyk have? Do they make art, or are their aesthetics strictly utilitarian? What makes them different from big, aggressive humans? We have no idea.

And for that matter, why should humans themselves feel so interchangeable? If they’re going to insist on showing us a galaxy that’s sixty-to-eighty percent human, there’s no good reason at all not to make those humans ridiculously variable, enough to make the Belters look positively boring in comparison. Ironically, the prequels underlined how big of a blind spot this is for Star Wars by giving us a huge amount of really cool human-presenting characters who a) never spoke or did anything and b) ended up being classified by the Expanded Universe as “near-human” Tholothians and Chalactans and what-have-you. Not only is that pretty troubling when you’re dealing with a big chunk of the films’ actors of color, it’s just plain dull—fantastic designs with absolutely nothing undergirding them.

I half-joked once that the nine-year-old Anakin Skywalker, having been raised bilingual on a Hutt-controlled planet, would more plausibly have spoken with a Huttese accent. Much like the science issue, I definitely don’t expect anything approaching verisimilitude from accents in the Star Wars galaxy, but that doesn’t mean they have to be completely irrelevant. Lucas’s attempts at distinct accents and dialects in The Phantom Menace had a lot of problems, clearly, but if The Expanse can craft a plausible future human dialect that doesn’t come off like a caricature, I’d love to see Star Wars take advantage of its total liberation from reality and vary both its humans and aliens a lot more, filling them out and bringing their histories into the story with them. It’d be one more reason to involve a more diverse range of voices and perspectives in the writing process, in fact—but much like with politics, I have to wonder if the franchise has learned the wrong lesson from the prequels here and gone too far in the opposite direction.

* * * * *

Star Wars isn’t science fiction; it can’t be approached the same way you would think about our own future. That’s a tough thing for lots of fans to get our heads around—but despite those ties to the real world, in some ways science fiction has the potential to be much more unconventional than Star Wars, whose films lately tend to be written as if from a top-secret formula that can’t be too much of any one thing. Now that the modern era has established itself, their next concern should be to keep everything from starting to feel samey, like much of the Marvel Cinematic Universe does. I hope Solo‘s underwhelming box office doesn’t make them afraid to keep varying the recipe and drawing from other sources, especially ones with track records as phenomenal as The Expanse‘s.

Great article! Chalactans were retconned back into humans, though.

Thank you! Yeah, that’s why I specified the EU. 😉