The first thing we ever learn about the Jedi is that they were the “guardians of peace and justice in the Old Republic.” Until I read Claudia Gray’s Master & Apprentice, it never occurred to me that this definition contains a contradiction. Peace and justice together are the defining conditions of the ideal polity. It’s an idealistic platitude too familiar to invite closer examination. That’s why it feels so revelatory when Gray shows us that in practice, Jedi often found that peace and justice were tragically at odds.

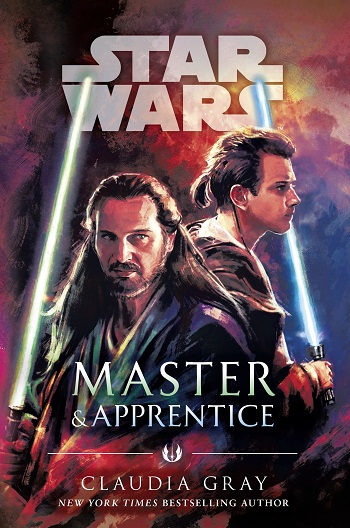

Master & Apprentice takes place eight years before The Phantom Menace, and reprises much of that film’s premise. Obi-Wan and Qui-Gon are sent to negotiate a deal between a planet’s willful teenage queen and a powerful, malicious corporation. Their lives are threatened by mysterious assassins, and they turn to a slave for aid. That overt similarity between the two stories allows Gray to take a second crack at a thematic question raised tangentially by TPM: is it right for the Jedi to ignore injustice in pursuit of the greater good?

In TPM, Qui-Gon doesn’t find this question very difficult to answer. He frees Anakin to gain a powerful Jedi, not to end the injustice of his slavery. He makes a half-hearted effort to win Shmi’s freedom too, but doesn’t press the issue. The question of freeing any other slaves never even comes up. They didn’t come to Tatooine to free slaves. The people of Naboo are counting on them; they can’t afford to get distracted by every injustice that crosses their path.

In Master & Apprentice, Gray makes things much more complicated. Qui-Gon’s mission should be trivial. He is there to signal the Republic’s approval of a treaty between the Pijali monarchy and Czerka Corporation. The Jedi Council approves of the deal because it will create a new hyperspace corridor bringing trade to poor worlds. What they don’t realize is that signing the treaty would make it legal for Pijal to sell incarcerated people to Czerka as slaves. This time, the injustice the Jedi encounter is not as easy to separate from their mission. And the people who are relying on them to complete their mission are in far less tangible peril.

What fascinates—and, to be honest, still kind of flabbergasts—me about this story, though, is that Gray makes Yoda argue against ending slavery. When Qui-Gon brings the slave clause of the treaty to his attention, Yoda’s response is “Jeopardize the hyperspace corridor, you must not.” Classic Yoda.

Qui-Gon pushes back, saying the Jedi should end slavery throughout the galaxy. Yoda responds by lecturing Qui-Gon on cultural relativism. The arachnids of Uro eat their weakest children. The Abyssin murder their elders to conserve resources. Does Qui-Gon think the Jedi should have the power to end these injustices too? The exchange culminates with this:

“[Slavery] is something humans do to one another, an atrocity we should put an end to.”

“We? Not the chancellor, not the Galactic Senate, not even the people of the Republic, but the Jedi?” Yoda thumped his gimer stick on the floor. “Want to rule, do you? Dangerous this is, in one who would join the Council. Dangerous it is in any Jedi.”

Qui-Gon knew all of this. On one level, he accepted the truth of it. On the other—“If we don’t stand for the right, what do we do? Why do we exist?”

And that suddenly seems like a pretty great question! If the Jedi can’t even prevent slavery within the Republic, what good do they do? As it turns out, this is surprisingly difficult to answer. Every Star Wars story set after Revenge of the Sith simply takes it for granted that the Jedi are not only good, but indispensable to the well-being of the entire galaxy. Luke in The Last Jedi is the only character to meaningfully question that assumption, and even he comes around before the end. No one ever bothers to say what exactly they expect the Jedi to do when they’ve returned, and why it is that no one else can fulfill the same role. To figure out what, if anything, the Jedi are actually good for, we have only the prequels to turn to.

Before the dark times

A common talking point of prequel fans is that the prequels are interesting because they condemn a group we thought were heroes. YouTuber Hbomberguy, for instance, has said “the Jedi are set up as the bad guys in the prequels” because they are “essentially enforcers for the supposed democracy of the Republic.” Prequel detractors, meanwhile, might argue that the text doesn’t support this reading. What I find most remarkable about this whole discussion, though, is that the prequels actually tell us very little about the Jedi.

Throughout the entire prequel trilogy, only four peacetime Jedi assignments are even mentioned. Obi-Wan and Qui-Gon are sent to “settle the conflict” between the Naboo and the Trade Federation. Obi-Wan helped resolve a “border dispute on Ansion.” Obi-Wan and Anakin are tasked with protecting Senator Amidala, and Obi-Wan is sent to discover the identity of her would-be assassin.

The prequels tell us that Jedi are bodyguards and investigators when necessary, but more than anything, they are negotiators. And George Lucas has said as much himself.

“Jedi [were] peacekeepers who moved through the galaxy to settle disputes. They aren’t policemen, they aren’t soldiers; they’re mafia dons. They come in and sit down with the two different sides and say, ‘Okay, now we’re going to settle this.”’

I just…don’t find that answer very convincing. If Jedi are first and foremost negotiators, why do they need to be trained from birth to sword-fight and run obstacle courses? Conflict mediation is a real career that people without Force powers can learn. In fact, mind-control powers seem like a liability for a neutral arbiter. Would you really agree to a negotiation in which the moderator can mind-trick you into agreeing to anything they want?

There are other plausible answers, but I think they hold even less water. Honestly, you have to be a bit willfully obtuse to even pose this question. Everyone knows what Jedi are: they’re heroes. Negotiation is just a pretext for putting the hero in the midst of a conflict. What Anakin doesn’t tell Padmé is that negotiations are always aggressive.

If this feels like a copout, retreating to metatext to excuse the absence of a coherent answer within the text, I agree. At least, I would for most stories. As I’ve argued here before though, Star Wars has a special relationship with its metatext. In short, the Force is a manifestation of the plot the characters can knowingly interact with without breaking the fourth wall. This is what makes the Jedi uniquely valuable to the well-being of the galaxy: The Force gives them access to the author’s moral values.

That makes a certain sense of the apparently strange policies the Order imposes on its students. Force-sensitives who are “too old to begin the training” aren’t just prone to the dark side for some arbitrary fictional reason. Being raised out in the real world, developing ideologies and affiliations, learning to covet comfort and wealth and affection, they become people instead of empty vessels for authorial notions of heroism. When it comes time for them to make an important choice, their decision is influenced by formative moments and individual values. Emotions and attachment pose the same problem. If you’re worried about saving Padmé, you’re not listening to the author whisper the right answer to the moral dilemma you’re facing.

When you put it like that, this sounds like a pretty decisive condemnation of Jedi as characters. The Force is a direct substitute for everything that makes a character interesting. And it’s no coincidence that some of the most interesting Jedi have always been the ones who violate those rules in one way or another. But this unique nature of the Jedi has been used more often to avoid dramatic questions than to raise them. Why is this character risking their life to save strangers? Where did they acquire the values they use to make life-or-death judgments? They just listened to the Force.

It’s not a particularly compelling answer. But Master & Apprentice finds in that anonymous heroism the seeds of a powerful dramatic tension.

The Press

The biggest paradox in political philosophy is that any force strong enough to protect and serve the community is also strong enough to exploit and oppress it. Even the clone army isn’t exempt. They’re raised from birth to serve, have no material incentives or ideologies to complicate their loyalty, and still they become a tool of oppression. Only the Jedi will refuse to do evil even when the people demand it.

And yet, even with that chief problem facing human politics resolved by mystical metafiction, the Jedi’s task is still fundamentally impossible. Peace and justice are too often at odds for even incorruptible superheroes to preserve them both at the same time. Individual Jedi travel the galaxy as heroes, digging up old injustices and bringing them to a violent resolution. But the Jedi Council sees the big picture, and they’re constantly anxious that one of their heroes will pick a fight that lights the fire that burns the whole Republic down.

This is a problem Star Wars usually ties itself into knots to avoid. In the original and sequel trilogies, acquiescing to the Empire would sacrifice both justice and peace. Picking fights isn’t reckless because fighting is the only option. Unforeseen consequences don’t matter because there’s no way for things to get any worse.

In the prequel era, things are very different. The Republic is a deeply flawed state, full of corruption, hypocrisy, poverty, and even slavery. But it’s also a tool that allows the Jedi to extend their influence and solve problems that would be too diffuse or just too big for them to address on their own. The Jedi Order, as an institution, sees the Republic as the best way for them to serve their principles. They’re willing to accept a degree of inequality and oppression as the price of long-term peace and a baseline level of justice.

That might strike us as an ugly utilitarian tradeoff, but as far as we know, it was the right choice. The fall of the Republic is by far the worst thing that ever happened to this galaxy. And it wasn’t precipitated by the Jedi’s failure to address the internal contradictions of a corrupt Republic. It was brought about by a single man who understood the impossible position the Jedi were in and knew exactly how to use it against them.

As a general rule, I’m not a fan of the “Great Man” model of history. In Star Wars, though, it happens to be true. And I don’t find it particularly objectionable, because Palpatine isn’t the subject of this story. He’s an external factor, a force of nature. It’s like the Hydraulic Press Channel on YouTube. You know the press is going to win. It’s not about the press. It’s about how each new thing squeezes and cracks before it breaks.

Palpatine knows the Jedi have committed themselves to the Republic. He knows they’re willing to quash their heroic urges to maintain political stability. Everything he does in the prequels serves to ask, “how far will they take that bargain?” Will they accept the services of a slave army? Will they lead a war that devastates worlds? Would they still do those things if the Republic was less democratic? Less just, less free? How bad does the Republic have to be, how horrendous can the cost of defending it get, before they challenge the Republic or abandon it altogether? The answer is that there is no line. And Palpatine knows that. He can keep ratcheting up the pressure and the Jedi will go along with it right up until they’re destroyed.

The truth is there was no alternate path that would have saved the Jedi. No matter how they approached the paradox of peace and justice, they would create vulnerabilities for Palpatine to attack. If they had challenged the Republic on slavery or inequality or corruption, it would threaten the power of every elected official in the galaxy. It would be even easier for Palpatine to win them to his side. If they had declined to participate in the Clone Wars, acknowledging that the Separatists had legitimate grievances or simply committing to nonviolence, they would leave the galaxy at the mercy of megalomaniacal psychopaths with superweapons. It’s hard to see how that would have ended any better for the Order or for civilians.

Not to worry, the glass is still half full

And if prequel-era storytelling had dug into this tension, it could have been truly great. Instead, they do everything they can to avoid it. In the prequels, the Republic comics, and The Clone Wars, these questions lurk in the background, more intimations of a dark future than pressing dramatic questions. Rather than using this exquisitely-crafted narrative device to crush their heroes, they carve out narrative bubbles where heroes can still do the right thing and be rewarded for it.

This is why I was so excited when Master & Apprentice named the tension inherent in the Jedi’s position. A nebulous sense of missed opportunity I had never quite been able to put into words suddenly snapped into place. With that conflict articulated, made central to the plot, surely the book would finally start to deliver on its implications. But…it doesn’t. It identifies the defining contradiction of the Jedi Order only as a tease. In the end, Gray sees fit to give Qui-Gon the happy ending he couldn’t manage in TPM: the slaves are rescued and the hyperspace lane goes forward. The no-win situation becomes a win-win, no tradeoffs in sight.

Part of me feels deflated by that. I’ve known for years that I wanted a certain kind of story out of Star Wars, and that the prequel era was in the best position to deliver it. And now that I’ve figured out exactly why that is, it seems like all our best chances to get it have already passed. Maybe it was foolish to ever expect anything else. Plenty of people have written off the idea that Star Wars will ever produce anything but simple heroic stories, and either made their peace with that or moved on. But while simple heroism is undeniably the franchise’s default state, and it’s naïve to think it could (or should) turn into Game of Thrones, I think it’s equally wrong to give up on it.

Weird, dark, ambitious stories have always been edge cases in Star Wars. But they’ve always been there, defining and expanding the edges of this universe. And there’s reason to believe the vision and effort it takes to bring these complex implications into focus are coming to bear now more than ever before. The original and prequel trilogies aren’t dead stories; they’re living texts constantly reframed by new material. Writers will always be looking for hidden potential in old content. Claudia Gray might not have given me exactly what I wanted in this story, but that doesn’t mean I won’t get it in the future. The best story about the Jedi and the tragic bind they faced is yet to be written.

One thing I find very interesting is that the arguments fans make to justify the Jedi’s (and even the Republic’s) stance on slavery are very similar to the arguments that were made for not ending the transatlantic slave trade in the 18th and 19th century.