Welcome, one and all, to the final Minority Report, my annual(ish) update on diversity in Star Wars’ screen and printed content. As discussed in my last report, I’ve reached the conclusion that this new era of the franchise has brought us to a point where it’s better that the raw numbers, which have been my bailiwick for more than ten years now, take a backseat and that representation—what types of characters we’re seeing and how they’re used—becomes the primary focus of these conversations. While I still plan on running said numbers for my own edification, I’m going to refrain from these regular updates and save my commentary for when and if something really noteworthy happens.

I first took on this project way back in the days of the Expanded Universe, where most new characters were coming from books and their demographics were both more uniform and harder to notice; now that movies and television are steering the ship, Star Wars has responded to this increased scrutiny with a boatload of new female characters, characters of color, and even a small but not insignificant population of queer and nonbinary characters. But while the weight of focus has shifted drastically away from the usual parade of white guys, there’s still a lot to discuss about exactly how characters like Rey, Finn, Poe, Rose, Holdo, Val, and L3-37 are used, how they intersect, and what messages their stories are sending.

The thing about that, though, is that I see my own role in those conversations to be much more that of a listener—and ideally, a promoter of great voices from within the relevant communities here at this blog. When I started tracking diversity it felt like no one else was paying attention to it at all (at least in the not-very-diverse forums I was hanging around in back then), so having real numbers to throw around was my way of holding up a flashing neon “PROBLEM” sign. Now that diversity and representation are a huge, flourishing topic of discussion, I see how much I still had to learn, and while I still believe sheer volume is a big part of the solution, this is about much more than which types of people we see walking by in the background and who they happen to be kissing.

Furthermore, with The Rise of Skywalker behind us and a fair amount of time before another film comes along, this felt like a good time to step back and do what I think my data does best: characterize our overall situation here in the dawning post-sequel era. Have the needles been moving, and if so, how far and in which direction? 2019’s data proved to be pretty interesting on that score, so let’s start there before moving on to a recap of how this series has grown and evolved over the past five years or so, and concluding with an analysis of the larger trajectories I’ve seen in that time.

Where are we now?

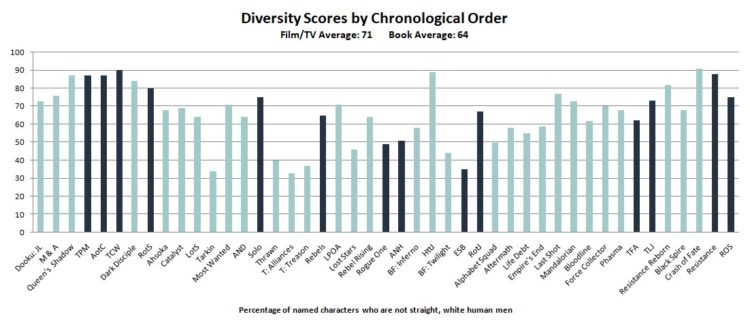

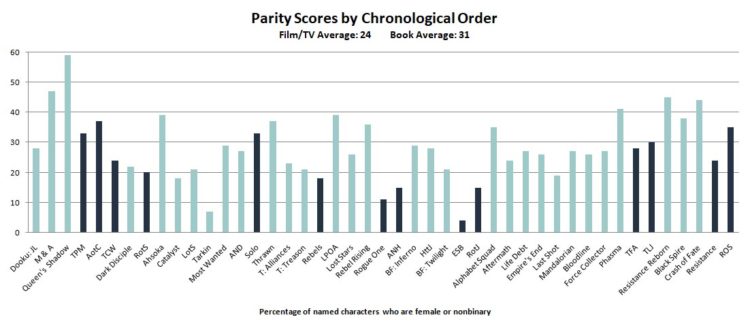

For the uninitiated, there are two metrics I track for this project: diversity scores, the percentage of named characters who are anything other than straight, white human men (WHMs, for short), and parity scores, the percentage of named characters who are anything other than male. When a character’s demographics are unclear, I count them as a WHM. This may seem unfair, and it definitely hurts some works more than others, but I’m operating according to the principle of proactive diversity: in a world where many readers will assume a character is white unless bludgeoned over the head with evidence to the contrary, if you’re not making at least some effort to communicate that a character is Asian, for example, then you shouldn’t get credit for the possibility that they could be.

That degree of uncertainty means that I won’t generally use a low score to label a source “bad at diversity”—but parity scores are another matter. Give or take what you regard as a realistic nonbinary population, there is very little excuse for a story featuring a random collection of individuals to not be around fifty percent female, because while novels often fail to describe minor characters in detail, they very rarely fail to give them a gender. I know this because I check—first on Wookieepedia, and then the text itself if necessary. I’ll actually have more to say on this later on, but for now, let’s dig into the most recent scores.

While it’s impossible to nail down an optimal diversity score—despite what they might tell you on YouTube eliminating WHMs altogether isn’t the goal here—I think the sweet spot is probably about 90, meaning one WHM for every ten characters. So I’m happy to announce that A Crash of Fate by Zoraida Córdova is the first new canon work (at least among the adult/YA novels and screen media) to pass 90, with the animated series Star Wars Resistance and Queen’s Shadow by EK Johnston right behind it.

And speaking of Queen’s Shadow, you probably won’t be surprised to learn—but it’s great nonetheless—that it was the first canon work to score over 50 on parity, with almost three out of every five of its characters being female. Studies have shown that men interpret male-dominated spaces as being closer to even and a truly even gender balance as being outnumbered, so the fact that QS only scored 59 is pretty interesting to me—if I wasn’t already so conscious of this phenomenon I myself might have guessed a much higher number.

Meanwhile, Master & Apprentice by Claudia Gray, Resistance Reborn by Rebecca Roanhorse, and A Crash of Fate all scored well over 40, while Delilah Dawson’s Black Spire came just a little short of that but still far above the sad average of 31.

You may have noticed by now that all the high-scoring books I’ve mentioned thus far have something in common; don’t worry, I’ll be getting to that.

Back over on the screen side of things, The Rise of Skywalker has a slightly above-average diversity score of 75 and more impressively, a parity score of 35, which is the highest for a screen property since Attack of the Clones a generation ago. While I was running these numbers another study was released that nicely echoed my results—film critic Becca Harrison came to my attention a while back thanks to her own pet project of adding up female characters’ screen time in the Star Wars films, and she recently found that ROS was the first one to crack fifty percent. In a piece at The Mary Sue she discussed her mild surprise at this revelation given the film’s perfunctory handling of many secondary female characters, and the sidelining of Rose in particular; this dissonance between the score and the story (see also: Solo‘s respectable score of 33) just underlines further how complex representation is and how much data can’t tell you.

Last but not least, Season One of The Mandalorian marked the first appearance of live-action television among my data, and behold, more dissonance: a series starring Pedro Pascal, Gina Carano, Carl Weathers, and a puppet scored only slightly above average thanks to a small collection of white guys in minor roles.

When you look at this year overall, though, the solid numbers for ROS and Resistance and the mostly impressive roster of novels resulted in noticeable jumps in all four average scores, most notably a four-point jump in novel parity from 27 (almost three-quarters male characters) to 31 (just over two-thirds). More on this later.

Where have we been?

In the original Minority Report piece way back in 2014, the entire Star Wars canon was six films, most of The Clone Wars, and one novel: John Jackson Miller’s A New Dawn. With a small named cast by novel standards, AND lost a lot of ground to its eight WHMs, so I took the time to actually list each of them and explain what we knew, or didn’t know, about their demographics. To my surprise and fascination, Miller himself commented on the piece, noting that he’d actually envisioned two of those characters as aliens—but had only given vague clues in the text itself.

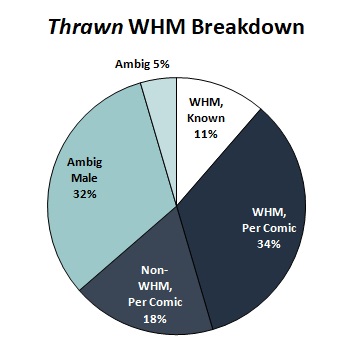

While I stand by my decision on this, in the back of my mind I’ve always wondered about that: what if I really went out of my way to be as fair as possible with ambiguous characters instead of just assuming they’re white guys? While I’ve definitely noticed a trend toward more proactive description of characters’s appearances over the last several years, I recognize that it’s a lot to ask of novels with a more military bent, which tend to have pretty big named casts thanks to random asides about Smith getting shot in the leg or Jones requesting backup over comms. Sure enough, neither of Alexander Freed’s two original novels, despite main casts as diverse as those in the sequel trilogy, managed to score over 50. Timothy Zahn’s three Thrawn novels haven’t fared very well either—the original only earned a diversity score of 40, and that was as high as he ever got.

That original Thrawn novel is an interesting case: if you asked me to describe a hypothetical book that was destined to score poorly according to my criteria I couldn’t do better than a military story written by a male author of an older generation. And sure enough, it has forty-four WHMs out of a named cast of seventy-three characters—a lot of novels don’t even have forty-four characters total. But you know what else the book has? An adaptation.

Another big reason I don’t give people credit for ambiguous characters is because back in the Legends days an original character could float around for years and years without ever getting a real description—and when and if that day finally came, the artist, having no information to go off of, would almost always make that character white. The new canon is new enough that opportunities for that pattern to continue have been sparse thus far, but the comic book adaptation of Thrawn is a huge, huge exception. So I thought to myself, why not be as fair as possible here? A lot of characters were ambiguous initially, but maybe some of them were nailed down in the comic? How diverse would Thrawn be then?

Well, a bit more, but not much. I revisited its list of forty-four WHMs one by one and when more information was present now than there’d been at the time, I made a note of it.

| 5 | Certain WHM |

| 15 | Confirmed as WHM later |

| 8 | Confirmed as non-WHM later |

| 14 | Unknown race/species |

| 2 | Unknown race/species/gender |

Only five of them were certain WHMs to begin with—movie characters, for the most part. A little over a third were confirmed as white in the comic, with another eight being confirmed as women, people of color, or both. [1]Comic book art is far from exact, of course, so I’ll further add that a few of those eight could have gone either way—but I really tried to be charitable here. Another fourteen didn’t show up in the comic, but had been established as male. Out of forty-four characters, only two remain total unknowns: Osgoode and Yelfis, characters who are heard briefly on comms but never “seen”.

It’s worth noting that one of those eight characters confirmed as POC by the comic is Eli Vanto himself; the novel makes no mention of his skin tone. You might be thinking at this point that Zahn just isn’t inclined to describe people’s skin at all, and that’s his prerogative—true enough. But I will say this: of the twenty-one references to skin in the book, seven are to blue skin. One for Ar’alani, and six for Thrawn himself.

So let’s hypothetically give Thrawn credit for those eight characters. If we take the ratio of WHMs among comic-confirmed characters—fifteen out of twenty-three—and project it onto the sixteen remaining ambiguous characters that means we can reasonably guess that another ten are WHMs as well. That plus the original five gives us thirty WHMs out of a full named cast of seventy-three, and an adjusted diversity score of 59.

Is that more fair? Arguably. If you want to go nuts and mentally credit that extra 19 points to the scores of the other Thrawn books, and even Twilight Company and Alphabet Squadron while you’re at it, the scores you end up with are in the 50s and 60s—still below average, but not absurdly so.

Speaking of average, my big takeaway in the Minority Report’s “Year One” update, now that I had a bunch more novels to consider, was just that: the canon numbers weren’t really any different than the Legends numbers. The characters seemed better, though; we were getting black and female Imperials in huge numbers, enough queer characters that we could afford to dislike one or two of them, and hey, how about the cast of Rebels?

Even if the scores remained average (at best) it was clear priorities were shifting. That sense carried forward into Year Two, which at last saw the arrival of The Force Awakens. It was clear by this point that scoring wasn’t going to tell the whole story, so I also broke down what I called the stages of inclusion: popular culture doesn’t become perfectly inclusive overnight, there’s a progression that tends to start with “token” characters like Leia and Lando and eventually, hopefully, arrives at what Riz Ahmed called the “Promised Land”, referring obliquely to Bodhi Rook—characters who just exist as people rather than representations (or refutations) of a demographic.

I also began tracking gender parity that year, which as I’ve discussed was a much more trustworthy metric—and the result I ended up with was that roughly one-fifth of Star Wars characters were female or nonbinary (the first nonbinary character, Eleodie Maracavanya, wouldn’t actually show up in my data until the following year).

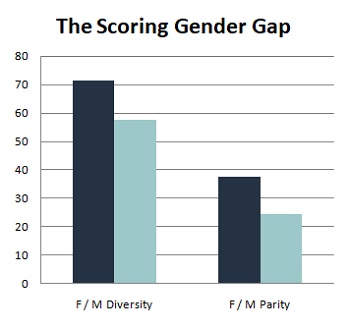

For Year Three, motivated in part by a distinct improvement in novel parity (and stagnant screen parity), I began looking at the gender demographics of the actual roster of authors. That year saw more novels written by women than by men for the first time—and lo and behold, those novels’ scores were 8 to 9 points better!

And that was a couple years ago. I dug back into those numbers this year, and was pleased to note that out of thirty original novels published in the new canon fourteen were written by women—just one shy of an even split. [2]I don’t score the novelizations separately from the films for reasons that are probably clear but insofar as this is about real creators getting real opportunities I will note that the ratio … Continue reading

And even better, that 8-9-point gap in scores has now increased to a 15-point gap in diversity and 14 points in parity! When you consider that parity only “needs” to reach 50 or so, a jump from 24 to 38 is absolutely enormous. I do want to stress here, though, that overall diversity among books written by women (72) still isn’t as high as I’d like it to be, but the difference can’t be ignored. Creators who aren’t white guys write books with fewer white guys—it’s a common, and obvious, refrain in these conversations but I’m happy to be able to offer some numbers to back it up. [3]Far less impressive is the fact that only three of the authors whose works I scored were people of color. And as best as I can determine, none of them have been from the LGBTQ+ community—though … Continue reading

Also that year, I was able to share a bunch of comic book diversity and parity data compiled by Ryan Malin of Mynock Manor—while I was thrilled when he offered to look into the comic side of things, the truth was that the numbers weren’t much different. Ryan’s still at it, though, and if you want to see his characterizations of more recent years check out his impressively thorough Star Wars Comics Year-In Review pieces, where diversity is just one of the trends he digs into.

With the end of the sequels in sight, Year Four was when I decided it was almost time to wrap this series up. That year had seen the birth of the #SWRepMatters social media campaign, and I asked some of its contributors to weigh in on my long-running struggle between the quality of representation we were seeing and the raw numbers. They also shared some of their favorite characters from the new canon—while there’s been precious little content that could be called perfect, there have at least been enough new characters that we’ve inched away from the problem of one woman having to represent all women, one character of color having to represent all people of color. Star Wars Resistance deserves a special shout-out here, with characters like Tam Ryvora and Torra Doza, Kazuda Xiono and Jarek Yeager, demonstrating the wealth of possibilities for whom women and men of color can be in the Star Wars universe.

And with that, we’re back to the present. But what do those last five years actually look like, data-wise?

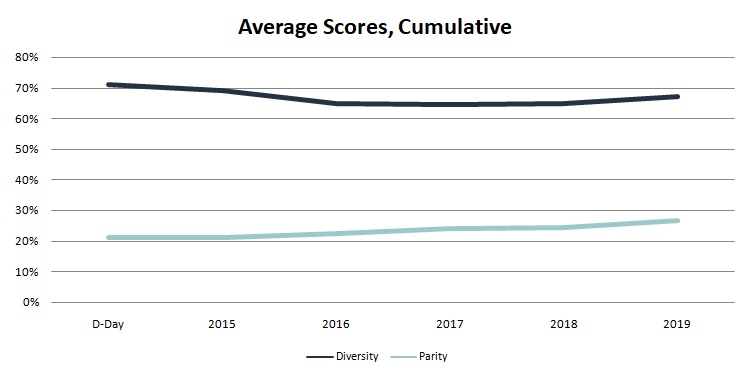

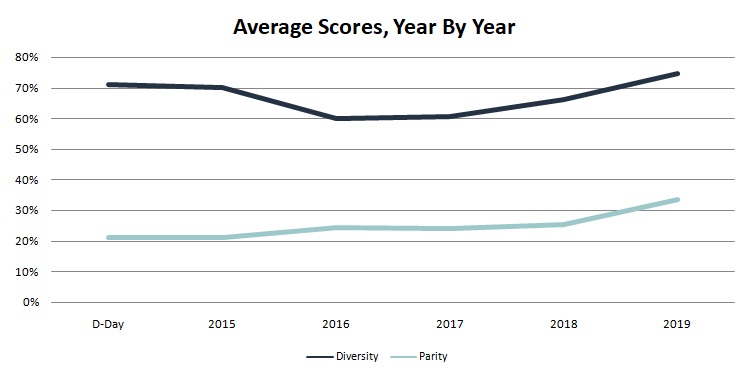

While scoring more and more content as time goes on definitely helps to paint a more accurate overall picture, it also means less movement is possible—even two or three really strong scores can’t move the needle much when weighted against thirty or forty older ones. That said, we can see the rough shape of some trends: a huge focus on Dark Times-era material in the first few years actually drove diversity scores down from slightly above the Legends average to slightly below it before making a modest recovery. Parity, meanwhile, exhibits a clear but slow upward trajectory. What happens, though, if we take the data year by year rather than adding it all up?

Here we can see some real movement—diversity’s downward trajectory post-reboot is much more pronounced, but so is its recovery, and 2019’s content brought us clearly above that original average of 71 for the first time. [4]My methodology here is weedy as hell but worth detailing for the record: the “D-Day” scores are for the six Lucas films and TCW, which were the entirety of canon coming out of the reboot. … Continue reading Parity’s steady improvement is likewise much more obvious: from 21 on D-Day to 33 today. In contrast to diversity’s big slump early on, I’m pleased to observe that overall gender parity never once went down, by either metric. If nothing else, I can say quite conclusively that the canon Star Wars universe has gotten consistently less male the entire time I’ve been watching. What that means for the characters themselves is of course a more complex discussion.

While it’s not clear from these graphs due to the numbers being merged, it’s also worth noting that the screen media almost always beat the printed media on diversity—sometimes by a lot—while the exact opposite was true for parity. While much hay has been made over the lack of diversity among film directors and screenwriters I think this speaks to the greater overall diversity of input that goes into a feature film, as well as the very gender-balanced yet overwhelmingly white stable of authors.

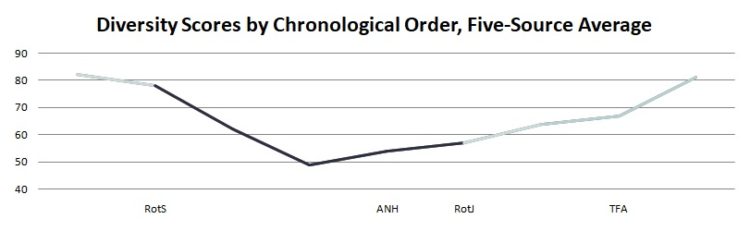

Where are we going?

While the Skywalker saga is complete (for now), we’re not yet walking away from that era entirely. Just look at those two chronological graphs at the start of this piece and you can see the noticeable dips that happen among stories set during the Empire’s reign; now that we’re seeing lots more prequel and sequel content I expect those scores to keep improving.

Since I picked on Timothy Zahn a fair bit earlier I’ll note that his upcoming Ascendancy trilogy will be (literally) new territory for him as he leaves the galaxy proper behind to finally focus solely on Chiss space—meaning that we’ll finally have a major story where there’s a solid reason not to assume minor characters are human. In the meantime I’m toying with the idea of scoring the original Thrawn trilogy for the first time, just to see how far he’s actually come.

The real star of post-sequel Star Wars publishing, though, will be the High Republic era—the first canon content with no WHM baggage whatsoever from the Empire, the original trilogy, or the Skywalker/Solo clan. I’ll definitely be keeping an eye on that and it’s possible that I’ll have observations worth sharing once the program concludes (or at least takes a backseat once the movies ramp up again).

One thing that’s definitely going to look very different a few years from now is television’s prominence in the franchise. I confess that I’ve never been totally satisfied with how the animated series integrated into the rest of my data because tallying a show’s entire cast at once tends to minimize the main characters, for both better and worse. Obi-Wan and Anakin, for example, only count toward The Clone Wars once despite being major characters in the majority of the episodes, whereas on Rebels and Resistance the overwhelmingly POC main casts tended to bump into a large assortment of WHMs from week to week.

For a time the only alternative I could see was to score episodes or seasons separately—which might produce results more comparable to your average film or novel but would give them a hugely outsize importance in my averages (not to mention make my graphs much harder to fit into an article). I’m still mulling this over, but with thirteen seasons of animated content now under our belts plus one season of The Mandalorian and at least three other series altogether currently in production I would be a fool not to continue studying television diversity somehow. If I had to bet on what my next piece under the “Minority Report” tag was going to be, something TV-specific would probably be it. With an ever-increasing—and already fairly diverse—pool of directors, writers and showrunners to consider, I may beef up my study of creator demographics as well.

And of course, sooner or later there will be new movies to talk about. A week ago, nobody had ever been hired to direct a Star Wars film who wasn’t, well, a WHM. More than a few had even been hired and let go! But last Monday, as I was waist-deep in preparing this piece, StarWars.com announced that they’d brought Māori director Taika Waititi on board to do just that.

Let’s hope he sticks around.

* * * * *

| ↑1 | Comic book art is far from exact, of course, so I’ll further add that a few of those eight could have gone either way—but I really tried to be charitable here. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | I don’t score the novelizations separately from the films for reasons that are probably clear but insofar as this is about real creators getting real opportunities I will note that the ratio goes down a smidge if you add in the two women and three men who wrote them. |

| ↑3 | Far less impressive is the fact that only three of the authors whose works I scored were people of color. And as best as I can determine, none of them have been from the LGBTQ+ community—though that information isn’t always out there so if I’m wrong I’d love to hear it. |

| ↑4 | My methodology here is weedy as hell but worth detailing for the record: the “D-Day” scores are for the six Lucas films and TCW, which were the entirety of canon coming out of the reboot. From that point on, each year’s scores were averaged after first giving equal weight to its screen media as a whole and its print media as a whole. For example, 2016’s two screen properties had an average diversity score of 67 and its five novels had an average of 53; these two numbers were then averaged to arrive at a final score of 60. The same principle applied to the cumulative scores, but with multiple years’ scores then being averaged as well. A book obviously has far less influence than a movie but given that there are several books printed for each screen property each one ends up counting for roughly a third what a movie or season of television does, which I think is defensible. Last but not least, note that the years given are approximations, as my updates haven’t always corresponded to the year a given source was released. |

This was interesting. Out of curiosity, I took your metrics and applied them to my own Star Wars writing. I got a diversity of 57.1% and a parity of exactly one-third (33.333%). I am a male author writing a Zahn-like military story with a lot of “unspecified” background/midground characters, so that seems pretty good compared to the average. I did have to make some judgment calls regarding the definition of “named” characters, since I have a lot of pilots known only by their callsigns and some of them are actually important and have screentime so leaving them all out didn’t seem right. I ended up deciding on a case-by-case basis whether a callsign-only character counted using the rule of thumb that three lines of dialogue or some significant action made you “named.” In the end, 11 of the 25 callsign-only characters with lines were counted as “named” characters.

I will say that if I could do a gender-based “screentime” analysis, I think I would do pretty well (since two of the five main viewpoint characters are female, one of the male viewpoints is almost always interacting with female characters and another male viewpoint is always in a squad with prominent female characters). The fact that main characters and one-offs are treated the same in this model is a significant (if understandable) weakness.

One thing this assessment did make me realize is that by coincidence (or maybe not) a disproportionate number of my major female characters are aliens. Of the starting batch of characters, only two are human women (one antagonist, one minor recurring support character) with a looks-human-most-of-the-time female alien viewpoint character coming later. Four significant human characters are male (though one is largely agendered) and of the two most prominent male alien characters, one is a near-human. I may need to make a conscious effort to balance that out in the future (though I do have plans for a number of female human characters of varying importance down the line, so the issue may take care of itself).

Overall, an interesting and thought-provoking (if unavoidably flawed in some respects) metric for gauging a serious issue.

For what it’s worth I do count callsigns/nicknames as named characters—the underlying intent is “was this character worth being specifically identified?”; the details of that identification aren’t that important. There have definitely been a few important unnamed characters over the years, and whole reams of trivial named ones but once you start making exceptions you undermine the whole thing.

Interesting idea. I did the same for a Star Wars RPG campaign I ran 2-3 years ago. Diversity score was 92% counting characters I created, 90% when I included player characters. It was helped by the fact that I often drew characters or used online art to represent them though, so no unknown characters.

As for parity score, it was 48% for non-player characters and 45% with player characters. It decreases to 43% and 40% respectively if I don’t count droids. Counting only humans, the diversity score decreases to 78% without players and 74% with. Humans made up about 30% of the total characters.