The final third of this piece contains spoilers for Poe Dameron: Free Fall. If you’d like to avoid them, stop when you see Babu Frik.

Governing an entire galaxy isn’t easy. As initially conceived, government in Star Wars was despotic and militaristic and led by people with magical powers—and even then, with no civil liberties or red tape to hold the Empire back, small pockets of rebellion were still able to slip through their fingers over and over, to say nothing of run-of-the-mill criminals like Han Solo.

As conceived, though, that was a good thing. The Empire was bad, so breaking its rules was justified, or at least a lesser concern to the good guys than what the Empire itself was up to. Even in the prequel era, the Old Republic is already riddled with corruption, and morality is often in conflict with the law our heroes are still desperately clinging to.

The sequels, then, were our first opportunity to experience a fundamentally righteous, if imperfect, galactic government—for about seventy minutes, anyway. Then it explodes.

But there’s a generation or so prior to that where even Luke Skywalker at his most cynical concedes that the galaxy was in balance, and a whole crop of younger characters managed to grow up with little to no awareness of how hard-fought that balance had been. For now, at least, that peacetime generation is unique in the canon, and crafting good, old-fashioned Star Wars adventures with them isn’t quite as easy as it used to be.

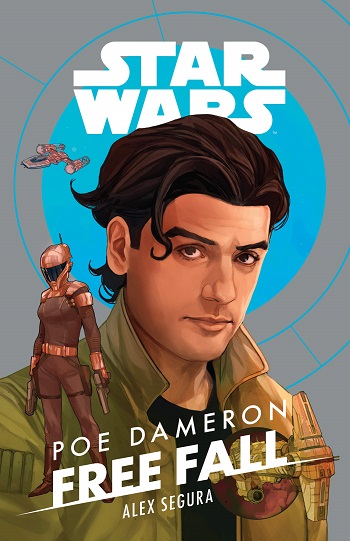

Exhibit A is Poe Dameron: Free Fall, the first major story set roughly in the middle of that time span—long after the fall of the Empire and long before the rise of the First Order, meaning there’s no external force at work to blame Poe’s problems on, just his own choices. What makes or breaks this story, then, is the specific context in which he makes those choices: what it says about his character, and what message we’re meant to take away about the underworld of this era.

Criminality under the Old Republic is most commonly shown to stem from overwhelming and indifferent bureaucracy. Qui-Gon Jinn can’t free Hutt slaves because he’s a Republic operative and such actions would amount to a declaration of war. Pax and Rahara’s gemstone smuggling operation in Master & Apprentice is an excellent illustration of a similar problem on a much more trivial scale: something that’s worthless on one planet might be priceless elsewhere, and adequately regulating those kind of inconsistencies across a million planets is too much for the Republic to keep track of, allowing one who goes to the trouble of specializing in such an area to make a living entirely between the cracks. Criminals can be good guys, this era tells us, because the law is wrong.

Then the Empire comes in and sweeps that bureaucracy aside with one comprehensive philosophy: what we say goes. Where the prequels were anti-bureaucracy, the original trilogy is anti-government altogether; criminals can be good guys, this era tells us, because the law is evil. So evil, in fact, that even smuggling drugs for a murderous gangster seems okay in comparison.

But crime is still crime, no? We rarely see Han Solo do anything truly despicable during his smuggler days, at least in canon—and Solo makes it quite explicit that he’s a good person just pretending to be a bad one—but his actions still support a power structure that exploits, enslaves, and murders people. Even Luke and Leia, when forced to contend with Jabba years later, attempt bargaining prior to open hostility. Though it’s clear they realize a fight is inevitable, they would prefer to expend that energy on the Empire, not a spice lord.

Which brings us to Poe, who shoulders a unique burden that one could argue is both unfair and possibly unresolvable. Caught between two opposing influences—the “cool” factor of the underworld and the ostensible righteousness of the New Republic—Poe doesn’t have Han’s excuse of no better options, so instead he’s driven to crime by nothing worse than boredom and an overprotective father. Further complicating this is Oscar Isaac’s real-life heritage; is drug running the furtherance of a stereotype, or just another stock Star Wars archetype that Poe is no less entitled to than Han was? Frankly, I’ve seen Latinx fans make passionate cases on both sides of this matter and it’s not my place to weigh in on it—except to say that these considerations matter.

So how does Free Fall handle this? Well, by avoiding it as much as possible. While we see the Spice Runners of Kijimi on several missions over the course of the book, at no point do we see them run spice. We’re told once that they operate a pipeline from Kessel to Kijimi itself, but Kessel is never visited, and Kijimi is held at a careful remove until the final act of the story, which has very little to do with spice. The actual timeline of Poe’s involvement with the group is very unclear—the Rise of Skywalker Visual Dictionary suggests five years and in one brief line at the end of Free Fall Poe thinks back over “the past few years”, but if you add up the actual events and time jumps detailed in the story we only seem to witness about a year go by [1]I will note that I was provided an early copy of the book and it’s possible these details were changed by the final edit. Things being as they are I was unable to cross-check the relevant … Continue reading—which suggests we’re only getting the briefest of glimpses into what Poe was actually up to for all this time, and given that they’re called “the Spice Runners of Kijimi”, those glimpses don’t seem to be especially representative.

What the book does do well, aside from making Poe and Zorii Bliss consistent and enjoyable characters in a believable slow-burn romantic relationship (however much I might side-eye that for unrelated reasons), is portray a gradually-escalating sequence of moral lines Poe is forced to cross until finally arriving at one he won’t. Whether that works for you, I think, will depend largely on your preconceived idea of just how immoral running spice is to begin with—because the book doesn’t even attempt to weigh in on that. Even the New Republic operative obsessed with tracking them down has a non-spice-related tragic backstory to explain her single-mindedness.

The Spice Runners are instead portrayed as a band of boilerplate outlaws that Poe falls in with simply to get away from his father, and stays with mostly out of affection for and loyalty to Zorii. It’s here that the muddled timeline really hurts the story, I think—a few months of that might be understandable, but a few years? Without being forced to commit any acts of true moral repugnance, give or take those countless off-page spice shipments? “Muddled” might honestly be a charitable word for it.

Star Wars’ recent young-adult output has been almost uniformly fantastic, and I’d be lying if I said Free Fall as a book was quite up to that par, but it’s worth adding that the sequel films in general, and The Rise of Skywalker in particular, didn’t do it many favors. I was willing to roll with Poe’s new “shifty” backstory if it meant interesting new stories could be told about him (“fighter pilot in peacetime” will only get you so far), but there was a serious dearth of “whys” for Alex Segura to work with here—not just why Poe would want to join a group like this, but why would Zorii, whom the film presents as a pretty decent-hearted person? For that matter, are the Spice Runners, in this era of good government, even necessarily a bad thing? Spice has been shown to have medicinal uses; for all we know they’re smuggling medicine to people and worlds the New Republic can’t yet reach—operating beyond the law rather than in brazen defiance of it. Criminals can be good guys, that scenario might tell us, because the law is inadequate.

There are compelling possibilities here, but Free Fall‘s tight focus on Poe’s internal journey offers very few clear answers. Being able to invest in our heroes’ flirtations with the underworld requires a degree of clarity regarding not just what drove them to that point, but the systems within which that underworld is operating. The sequels didn’t provide Segura with either of those, and if he didn’t manage to build them out enough for my liking I don’t know how much I can blame him.

Thanks to Disney-Lucasfilm Press for allowing me early access to Poe Dameron: Free Fall for review purposes.

| ↑1 | I will note that I was provided an early copy of the book and it’s possible these details were changed by the final edit. Things being as they are I was unable to cross-check the relevant quotes on release day but I will update this piece accordingly if that proves to be the case. |

|---|

This is exactly the sort of thing I expected to happen from the very moment in the theater they said Poe used to be a drug dealer. Drop the casual latino dealer stereotype in for a quick plot hook, then explain it away as a disaffected playboy upset with status/daddy/authority, never actually deal with the weight of what it means to the character, much less deal with the baggage this trope brings. It seems the reaction amongst latinos in the US might have been more mixed; in Brazil it was a unanimous recognition of “oh there it is, welp, never expected otherwise”. Some complaints, some jokes, overall one more character in the bin of loose criminality for criminality’s sake.

Rant aside, excellent analysis on how crime is dealt with in Star Wars, Mike, thanks for the piece.

I remember a similar pattern playing out after TLJ—some female fans saw the Skywalkers as so central to the saga that making Rey a nobody was denying her validity as a protagonist, others saw it as an overdue upending of a problematic heritage trope. Sometimes progress means creating a new paradigm but sometimes it just means expanding access to the old one, and there doesn’t seem to be one strategy that’s ever going to please everyone, especially factoring in cultural differences as you noted.

I tend to be in the camp that in 10-15 years once the dust settles things will sorta just sort themselves out. Not saying the arguments on representations aren’t valid, but in terms of retcons and lore and what not give it a generation and people will just accept it as part of the story and find work arounds. They always do.