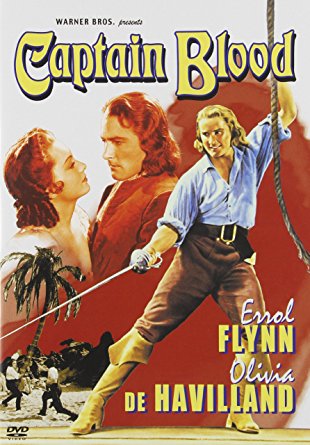

What is swashbuckling adventure? The term conjures images of dashing heroes rescuing damsels in distress via energetic swordfights in a romantic historical setting. It should be obvious that there is some of this in Star Wars’ DNA: it is dominated by dashing, high-octane heroic adventure, and sometimes openly apes the tropes of swashbucklers. Twice, a lightsaber-armed Luke Skywalker rescues Princess Leia and escapes by swinging across a gap on a rope (it’s not real swashbuckling adventure until somebody swings from a rope, vine, or whip). At its core, Star Wars is a spiritual descendant of swashbuckling adventure, which means the genre should occupy a significant place in the Expanded Universe.

There are certain tropes that go along with the swashbuckler: elaborate fencing-centric action sequences, romance with a damsel in distress, a bold and idealistic hero fighting against oppression or cruelty, a wicked villain in a position of power (who must inevitably be defeated in a swordfight), a historical setting of approximately 1200-1800 (or a fantasy version thereof). Think Robin Hood. But fundamentally, swashbuckling adventure is about an attitude. A swashbuckler’s approach to entertainment is energetic and flamboyant: its characters are larger than life, its plot one of constant thrills and excitement, its tone exuberant. It is almost never in question that the hero will win; the point of the story is to enjoy the fun-packed journey to victory.

Read More

A few weeks back, a

A few weeks back, a  One of our bigger early successes, traffic-wise, was a piece from Lucas Jackson on “the rise and fall of the supporting cast” in the Expanded Universe. Having interacted with Lucas on the

One of our bigger early successes, traffic-wise, was a piece from Lucas Jackson on “the rise and fall of the supporting cast” in the Expanded Universe. Having interacted with Lucas on the  When we were first getting this site up and running, I took a couple old pieces of mine from

When we were first getting this site up and running, I took a couple old pieces of mine from