Inspired by my friend Barriss_Coffee’s lament of his treatment, I recently realized that Count Dooku is among the major film characters most mishandled by the Expanded Universe. Unfortunately, in this it only follows the example of the films. Yet it is not hard to imagine an excellent use of Dooku’s tremendous potential. A few books and comics have done so, but all too much of the prequel EU has done Dooku a serious disservice by treating him one-dimensionally and neglecting him as a character.

Conceptually, Dooku is a great character. Played by the iconic Sir Christopher Lee, he is a former Jedi Master of great power and prestige who left the Jedi Order, disgusted with its ineffectuality and subservience to the corrupt Republic, after the death of his maverick apprentice Qui-Gon Jinn. He fell into the orbit of Darth Sidious, who convinced the prideful Jedi that the key to reforming the galaxy was in Sith authoritarianism and turned him to the dark side. Dooku then spent ten years plotting with Sidious to bring about the rise of the Sith. He made use of his image as a disaffected Jedi Master to pose as an idealistic reformer who led a secessionist movement and created the Confederacy of Independent Systems, which he then led in a puppet war designed to bring about the rise of a Sith-controlled Empire.

There’s a lot of meat in that character concept. A respected Jedi Master who leaves the Order for essentially sound reasons but is corrupted through pride into a devious Sith Lord, only to pose for the public as a principled firebrand throughout a political crisis to dupe the genuinely ineffective into a phony war? That’s a layered character, one perfectly suited to the dark charm and gravitas of Christopher Lee.

Yet the prequels themselves did the character few favors. Due to Lucas’s unfortunately on-the-fly writing habits during the prequels, he wasn’t set up by The Phantom Menace. In Attack of the Clones, Dooku was barely introduced. He was mentioned in early exposition, then ignored for the rest of the movie, until he turned up on Geonosis near the end. The scene in which Dooku told Obi-Wan of the Republic’s corruption and Darth Sidious’s role offered a tantalizing question of his motivations, but that mystery was never really explored. From holding Obi-Wan prisoner to attempting to execute the heroes to whipping out a red lightsaber and Force lightning for their duel, there was never any real question that Dooku was a villain, robbing his reveal as Sidious’s apprentice Darth Tyranus of any punch at the end of the film. Dooku’s treatment was perfunctory; rather than build him up or hold him as a presence over the film, or play on the question of his agenda, the film ignored him and his Separatist crisis while it focused on Kamino and romance, then gave Lee only a handful of scenes near the end to set up the battle, then duel the heroes. Compare Dooku’s facetime (or even add on his presence in exposition) to that of any other Star Wars villain, and you’ll realize just how much he was ignored by his own film. Not only wasn’t his potential fully tapped; he wasn’t even used outside the third act.

He was treated even more poorly in Revenge of the Sith. Having been awkwardly dropped into the end of the previous film, he was summarily dismissed in the opening sequence of Revenge. He walked into a room, dueled the heroes, and died, so that the role of main Separatist villain could be taken over by General Grievous. The character who was supposed to be a pivotal figure in the Clone Wars, a character of great potential played by an iconic actor, was hustled in and out of the films with little attention paid to his narrative role and no sense of respect for his potential.

The Expanded Universe, theoretically, is the place to remedy this sort of inattention, expanding the characters beyond their limited screentime. This was especially the case for Dooku, given that the films left the Clone Wars, Dooku’s heyday as a major character, to the EU to tell. Yet the EU has largely failed to run with the ball. His backstory has been relatively little touched; the fandom is still waiting for a real exploration of his time as a Jedi, his decision to leave, and his fall to the Sith.

Yet even more frustratingly, the complex and intriguing character promised by his character outline has largely failed to manifest in the Clone Wars EU. In part, this is symptomatic of the shallow handling of the Separatists in general, as my colleague Jay has pointed out. But it is not entirely a result of that issue; it also stems from a seeming lack of interest in using Dooku himself, rather than using his underlings as lead villains. In the television series, which could have done the most to develop and exploit the character, Dooku was largely limited to appearing as a traditional, generic evil overlord who chewed out his minions and cackled evilly. In most of the Clone Wars works, he appeared only briefly, sending off some lackey to battle the heroes. Supposedly a major film villain, he seems lucky to get any serious attention as a character at all.

Frustratingly, very little has been done to honor Dooku’s public role as an honorable reformist, or explore the complexity of his character. During the Clone Wars, he has mostly been portrayed as a generic evil overlord with minimal story involvement. Before the Clone Wars, he has been reduced to essentially a handful of cameos. The potential of this multilayered character, the tragic arc of the flawed crusader turned deceitful, devious tyrant, has been mostly untapped.

Fortunately, it has not been entirely untapped. John Ostrander has proven one of the few authors working on the initial Clone Wars run to truly get the character of Dooku and put him on the page. His run on the Republic comic series showed Dooku as a charismatic, sophisticated deceiver, malevolent in private but benevolent in public, who seemed to genuinely believe he would make the galaxy better through the power of the dark side but was unhesitating in plunging into secret wickedness.

Ostrander’s Dooku was especially well-done in Jedi: Dooku, which began with Dooku capturing a ship with several Jedi aboard, among them one who has had her doubts over the Republic’s rightness in the past. By claiming that his prior actions were misunderstood, proclaiming brotherhood with the Jedi, and letting the captured Jedi go, Dooku played to his political-idealist public image while sowing seeds of doubt within the Jedi Order about their leaders’ truthfulness, Dooku’s nature, and the rightness of their cause. Dooku later went to Tibrin, where he defeated its pro-Republic leader, executed the unpopular tyrant and had his head displayed rather than accept his offer to join the CIS, ordered the entire inner circle of the government slaughtered, and emerged before cheering crowds as the planet’s savior. Ice-cold, crafty, and bloody-handed in private; a benevolent liberator in public, conscious of his principled, wise public image and using it as a weapon. At the end of the comic, Dooku revealed that he knew all along that Quinlan Vos, the Jedi agent posing as a convert to infiltrate his inner circle of darksiders, was actually a double agent. He had been pushing Vos toward a genuine fall, and using a combination of exhortation about the genuine grievances of the Separatist cause, seductive invocation of the power of the dark side as a force for change, and emotional manipulation of Vos’s past and the secrets of his family, he managed to push Vos into murdering a relative in anger.

This version of Dooku brought out all the qualities Dooku ought to have. He was a sophisticated, icy chessmaster, a devil who could almost casually corrupt men’s souls, but also capable of playing the charismatic firebrand, the grandfatherly and regretful reformist, with consummate ease. Ostrander honored the complexity of Dooku’s character rather than reducing him to a one-dimensional cackling supervillain.

The other major triumph in Dooku characterization was Yoda: Dark Rendezvous. Sean Stewart’s plot was premised on the idea that Dooku attempted to lure Yoda into a trap with a message of regret for falling to the dark side and starting the Clone Wars, asking to broker a truce and return to the Jedi. Yoda pursued the meeting, even knowing it was a trap, because he believed that Dooku, consciously or not, actually did wish to be redeemed and escape the grip of his Sith Master.

Dark Rendezvous thus focused on Dooku’s multiple layers as a fallen Jedi through his relationship with Yoda. A prideful and ambitious, but talented and idealistic youth, he forged a bond with Yoda; after his fall to the dark side, Yoda appealed through that bond to convince Dooku of the truth: that the dark side was in irretrievable conflict with the principles that had led him away from the Jedi and ultimately to the Sith. Dooku appeared to be on the brink of expressing his suppressed remorse and returning to the light side, until Anakin and Obi-Wan arrived — plunging Dooku back into wrath and pride at the intrusion of a pair of Jedi he envied and resented. Stewart thus explored Dooku’s psychological complexity and history by addressing the inherent contradiction of seeking good ends through evil means and the character flaws that made Dooku ripe for evil.

These were not the only times the Expanded Universe did Dooku justice, but they were the best at using Dooku’s multilayered potential. They stand in contrast to so many works that have used him superficially and failed to honor his depth as a character. If only The Clone Wars had taken a hint from these works, the series might have delivered a rich, menacing, and complex villain. If other prequel works would put him front-and-center instead of treating him as dismissively as the films, they might find a great character around whom a lot of drama can be built.

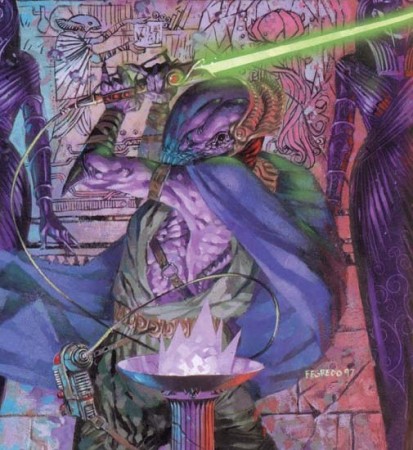

My understanding of Daoism is based upon, of all things, the Star Wars mythos. In particular, I can cite the New Jedi Order novel Traitor as being the key to my understanding of Daoist teachings; the author has a much more thorough grasp of the Force’s philosophical roots than George Lucas himself could ever dream of. The novel follows Jacen Solo’s journey of self-discovery while in captivity. For those who have not read the New Jedi Order, Jacen Solo is the oldest son of Han Solo and Leia Organa Solo, and twin brother to Jaina Solo. For those readers who haven’t read the New Jedi Order (and are likely unaware of the fan debates surrounding it), In the novel Traitor, Jacen Solo is held captive by the invading Yuuzhan Vong in the aftermath of the Jedi Strike Team’s assault on a Vong bioweapon facility, and the resulting death of Anakin Solo. Jacen is taught by the enigmatic Jedi known as Vergere, an unorthodox figure who has since been smeared as a “Sith”. But the epithet “Sith” cannot be further from the truth of Vergere—who herself does not exactly consider the spoken word, the name, or indeed language itself, to contain more than a glimmer of the truth. Like a good Daoist, Vergere recognizes that any truth which can simply be described, quantified, or categorized by words isn’t really a truth at all. Rather than being a product of Sith teachings, Jacen’s revelations teach him to love the universe for all of its faults, find his inner strengths, and use these to further the cause of “Tian”—the process of heaven on earth.

My understanding of Daoism is based upon, of all things, the Star Wars mythos. In particular, I can cite the New Jedi Order novel Traitor as being the key to my understanding of Daoist teachings; the author has a much more thorough grasp of the Force’s philosophical roots than George Lucas himself could ever dream of. The novel follows Jacen Solo’s journey of self-discovery while in captivity. For those who have not read the New Jedi Order, Jacen Solo is the oldest son of Han Solo and Leia Organa Solo, and twin brother to Jaina Solo. For those readers who haven’t read the New Jedi Order (and are likely unaware of the fan debates surrounding it), In the novel Traitor, Jacen Solo is held captive by the invading Yuuzhan Vong in the aftermath of the Jedi Strike Team’s assault on a Vong bioweapon facility, and the resulting death of Anakin Solo. Jacen is taught by the enigmatic Jedi known as Vergere, an unorthodox figure who has since been smeared as a “Sith”. But the epithet “Sith” cannot be further from the truth of Vergere—who herself does not exactly consider the spoken word, the name, or indeed language itself, to contain more than a glimmer of the truth. Like a good Daoist, Vergere recognizes that any truth which can simply be described, quantified, or categorized by words isn’t really a truth at all. Rather than being a product of Sith teachings, Jacen’s revelations teach him to love the universe for all of its faults, find his inner strengths, and use these to further the cause of “Tian”—the process of heaven on earth. When I’m explaining this site to people, one of the most important points I have to make is that the tone is intended as Expanded Universe-conversant, without being totally mired in thirty years of miscellaneous continuity. A lot of people still speak in hushed tones of the great Canon Wars, wherein the “everything counts” people waged a holy crusade against the “only the films count” people that rivaled the Galactic Civil War itself, but in my experience, for every Star Wars fan I know who’s actively opposed to the EU, there are five to ten who are at least dimly aware of it, and consider it more or less a valid enterprise; it just isn’t their thing.

When I’m explaining this site to people, one of the most important points I have to make is that the tone is intended as Expanded Universe-conversant, without being totally mired in thirty years of miscellaneous continuity. A lot of people still speak in hushed tones of the great Canon Wars, wherein the “everything counts” people waged a holy crusade against the “only the films count” people that rivaled the Galactic Civil War itself, but in my experience, for every Star Wars fan I know who’s actively opposed to the EU, there are five to ten who are at least dimly aware of it, and consider it more or less a valid enterprise; it just isn’t their thing.