One of the staples of the starfaring genre of science fiction has always been the presence of distant, foreign worlds, usually home to alien species but at the same time also conveniently capable of sustaining human life without any sort of environment suits or breathing masks. They’re right up there alongside faster-than-light travel, aliens that look suspiciously like people painted in funny colors with antennae taped on, and a questionable-at-best grasp of the laws of the physics.

In this, Star Wars is little different from any other similar franchise: in fact, many undoubtedly owe a great deal to it in terms of inspiration. While it may not have invented the concept of worlds consisting of a single, uniform environment, it undoubtedly popularized it to the point where Tatooine and Hoth have become the iconic desert and ice planets.

While the Original Trilogy kept the nature of the worlds it visited fairly simple, likely due more to a limited budget than anything else, the Prequel Trilogy revealed an entirely new array of diverse and captivating environments to us. The galactic capital of Coruscant was, as accurately described by the aptly-nicknamed “Captain Obvious,” one big city. The stormwracked ocean planet of Kamino gave rise to the titular army in Attack of the Clones. Revenge of the Sith further upped the ante by adding far more worlds than any movie before it: Mygeeto, Felucia, Saleucami, Kashyyyk, Cato Neimoidia, Mustafar, and Utapau.

Most of these were not visited for as long as the crew might have liked and left a great deal still on the drawing board (the crystal planet of Christophsis from The Clone Wars is based on one of a number of abandoned concepts, and Kashyyyk was at one point imagined with a Venetian influence), but they still served their general intended purpose of giving the Clone Wars that sense of scale that Galactic Civil War couldn’t quite achieve within the technological limitations of its time.

One would think that with launching off points such as these, and no expensive computer-generated imagery eating away at its production budget, the Expanded Universe would have gleefully taken to thoroughly exploring these alien worlds and creating countless others, each more amazing and wondrous than the last. Somewhat surprisingly, this can’t really be said to have been the case. By far, the most unique and memorable worlds have been the products of the franchise’s various tabletop role-playing games.

When not revisiting the worlds of the saga perhaps more than strictly necessary (hello, Tatooine of 3,956 BBY), the Expanded Universe has largely been content to treat most planets as brief stops along a road trip across the galactic countryside, more akin to villages and towns in our own world than the countries home to billions that they’re theoretically closer to. Characters are frequently assigned homeworlds from which they hail, yet only a small handful ever display any signs of having been influenced by the culture of the place where they were supposedly raised. On those occasions where a particular planet receives a more detailed treatment, it’s often limited to a single work and rarely revisited.

While it cannot be denied that Star Wars is, first and foremost, a tale of conflict told on a grand stage encompassing hundreds or thousands of worlds, the fates of those worlds hold very little meaning to us as long as we know next to nothing of them or their inhabitants. Leia’s homeworld of Alderaan is quite memorably destroyed in A New Hope – but that is precisely all that it is to us. Leia’s homeworld. At that point, we had never met its people. Never laid eyes on its surface. Knew next to nothing of its society or culture. A perfectly understandable narrative choice, given that it was the very beginning of the saga and there was little room to fit in an Alderaanian prologue (a problem rectified by the much lengthier and also exceptionally good radio drama), but that does not mean that it must always be so.

We could have gone back later and added weight to the tragedy by giving us an opportunity to know those whose deaths were predetermined. Alas, when The Phantom Menace was being developed the decision was made to focus on the entirely new world of Naboo instead, and the Expanded Universe has never been particularly enthusiastic when it comes to predetermined endings. Especially ones where everyone is guaranteed to end up dead.

For all the franchise’s reluctance to tie a story to a single world as strongly as the first of the prequels did, however, it has done so successfully on several occasions. In one particularly notable example, Aaron Allston’s X-wing: Starfighters of Adumar revolved around a competition between the New Republic and the Imperial Remnant to win over the loyalty of the titular world. Due to its unique culture, in which piloting skill is prized above almost all else, the delegation consisted primarily of pilots from the legendary Rogue Squadron, making for some highly unusual negotiations. Despite the story’s obvious divergence from the saga’s typical subject matter, it worked. Extraordinarily well, in fact.

And it’s hardly a concept limited to a single occasion: in a galaxy devastated by war as a frequently as this one, there are always worlds to fight over, and the number and variety of alien species mean that there will never be a shortage of new and interesting societies to navigate. More in keeping with the franchise’s conflict-driven nature is the MedStar duology, similarly bound to the world of Drongar, which possesses an extraordinarily valuable resource that both the Republic and the Separatists are desperate to get their hands on. Again, a concept that works in almost any era, and in this one is actually handled from the perspective of a behind-the-frontlines medical unit.

The Cestus Deception, another novel from the Clone Wars, does something similar when the Republic dispatches a team to ensure that the world of Ord Cestus does not sell a new type of deadly battle droid to the Separatists, by any means necessary. Perhaps the single most triumphant example of any story contained to one planet’s surface, however, is Shatterpoint. Matthew Stover’s famous trip home to Haruun Kal for Mace Windu sees the Jedi embroiled in a proxy war between the Republic and the Separatists, and eventually drawn into conflict with a powerful native warlord.

A significant part of what made stories like Shatterpoint and Starfighters of Adumar so successful was that the worlds they took place on served as far more than just a stage for the story’s conflict to be fought upon. Anyone can drop characters on a deserted world and have them fight to the death over it – that’s the easy part. What matters here is that the worlds themselves are integral elements of the plot: their societies, cultures, and traditions are all inseparable aspects of the battles and wars that our heroes are caught up in.

When we look at planets as more than just colorful backdrops for the action, everyone benefits. The stakes go up. When planets are menaced, more is on the line than just names on a map. It’s the difference between telling someone a disaster happened on the other side of the world in a place they’ve never been, and telling them that it happened somewhere they’d visited before and had fond memories of, perhaps having vacationed or even lived there. More options open themselves up for the authors, as well: wars can occur between rival planets or regional powers instead of every conflict having to threaten the existence of the entire Republic or the fate of the galaxy.

Your heroes can have a much more personal stake in the story when it’s their own homeworld on the line. Alien species can be given depth beyond simply looking different from humans, and the nature and difficulties of interspecies communication and interaction in the galaxy far, far away more thoroughly examined. Even continuity stands to gain from such an approach: the story of a war between planets is far less likely to require overwriting or come into conflict with future works than sundering the galaxy with another civil war or devastating it with an alien invasion from beyond the great void.

Going forward, I expect that the Sequel Trilogy and its spinoffs (and their spinoffs) will add a considerable number of new planets to the franchise. Seeing as there are now very few canon planets beyond those seen on screen during the saga, this is an excellent opportunity to reshape the galaxy so that each and every major world is given the depth it deserves, and made worthy of hosting many adventurous tales of its own. Before its retirement, the Expanded Universe had created thousands of planets, many of which existed solely for the sake of existing, never to actually be visited or used in a meaningful way.

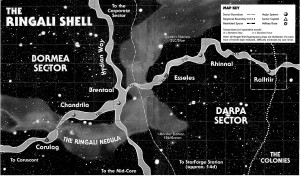

Worlds like Corulag and Esseles were established as being of galactic significance, but their importance was rarely (if ever) reflected in actual stories. We’ve seen far more of Tatooine, the farthest planet from the bright center of the universe, than we ever have Chandrila, founding member of the Galactic Republic and home to the leader of the Rebel Alliance. What we have now is the opportunity to create a galaxy full of worlds that actually matter, in which a planet’s own history is no less interesting than that of the Republic to which it belongs and where we can follow stories of worlds existing under the Republics and the Empire with the same degree of interest as we do for their inhabitants.