When you look into the hole in your heart, what do you see? A loneliness, empty black, endless as the sea of space stretching infinite. There is no escape from the world, the real world, the one crumbling and burning and flooding and filled with sadness. Or maybe there is—too-sweet coffee from the chain down the road (don’t think about the labor conditions of the growers); the vivid sky as the sun sets over the sea (don’t think about how the smoke adds to the beauty); a silly little show about space once a week, while it lasts (don’t think about how the industry is being eaten alive by conglomerates).

Cynicism. Optimism. Realism. Where do you fall? Where do I fall? Where, in the end, does Andor fall? Not just the show, but the man himself. When he looks into the hole in his heart, what does he see?

When he looks into the sky, is it blue?

Easy answer: no, it is not. Mostly it is grey, or entirely stolen away by architecture and brutality. Andor is a show about fascism, and revolution. We are shown oppression, real and fictional and fictional but far too real. Tony Gilroy takes us like a puppy and rubs our face in the dirt, asking us, Do you understand what is happening now? and it is done with such brutal beauty that it’s hard to believe this is actually Star Wars.

The Mandalorian (deep grey clouds) once promised a grittier, more grounded Star Wars. Strong shadows, dark moons, bounty hunters with snappy lines. Sharp, silver armor, untainted by the childhood colors of Boba Fetts in the toybox. Silver like the knights of old, the men of mud and blood and smoke. The Mandalorian was to be a man, a real man, unlike—uh, the rest of the men of Star Wars, I guess. We watched the unravelling of the myth in real time, as Din Djarin stumbled through his first day as a protagonist like some kind of Star Wars Sailor Moon, and wound up a dad. This was no underworld, but the upper world of goofy puppets, vivid blue shrimp, kids’ cartoon shows, and surprising love.

What would Mando see in his heart, if he looked? We will never know; the show doesn’t care to consider it. Din is a prop piece in his own world, a puppet for big men playing little boys in a universe far removed from his. Those strings, invisible, infinite. He is a fake man. A simulacrum of a noble warrior. We know this to be true. Must stories, then, mean something?

Suspend your disbelief, for a brief moment. There is a synonym for heart, and it is theme. Dig your hand into the core of any story of meaning, and you will be able to grasp its theme, notice between your caressing fingers the way it beats, how alive it feels. There are stories that stumble along like zombies, and in their silhouettes is the space where their own creators tore out their hearts. Must we step in that literary blood and celebrate the fun? How grim.

Experience this in real time: watch The Book of Boba Fett (a surprisingly clear sunset). Boba. Not Mandalorian. Not clone. Not like the others, only like one. In the mirror is the face of his father’s. The man has no home. He’s never been evil; he’s lost. There is depth here. Press your ear to his blast plates and there is that beating theme. Laughter, too, because it’s Temuera Morrison under that helmet and he radiates. In Aotearoa, our cultural storytelling intertwines comedy with tragedy, like lovers. Levity is as valuable as depth. The ingredients are all here.

Boba Fett stood tall, at first. A story about people driven from their homes, lives taken by capitalism and corruption. Indigenous stories, connecting real-world struggles with those of fictional characters treated like—Coop can I say shit?—shit. Morrison himself, dancing as he fought as if it were a taiaha in his hands rather than a gaffi stick. Could Star Wars carry that message, could the average viewer see that meaning and draw parallels, and see the real world in a new light?

“Don’t worry about all that,” Boba Fett said, as its heart slid out, onto the sand, and fake Luke Skywalker stomped right over it.

This metaphor is getting grim. If I am being mean, it’s only the depth before the levity. Look, the sun is rising, and it’s called Rogue One.

The perfect story is one where you know the protagonists are marching to their deaths. My ideal novel will end on the apocalypse, and you will know with full horror that it is coming. It’s no surprise, then, that Rogue One is the best Star Wars movie. There is beauty in tragedy—the gaps before the end leave such rich space to fill. Characters can grow into something quite different when their end is already decided. There is more space for nuance, to fit the details. Every single moment is thick with the immense pressure of finality. We know the ending but not why. Not how. Not the emotions. Tension blooms not from will they live but from how the hell are they getting out of that alive?

Rogue One is a tragedy with a heart of hope. A dichotomy that leads to a movie ending on a sunset of a kind actually being a sunrise of a film. Our heroes fade into stardust, but their memories remain bright. Their efforts mattered. They saved the universe, even if they will never know it. When the Death Star exploded into a million fascist pieces, that was because of the people of Rogue One—and not just the main characters. The light isn’t quite here yet, but it’s coming. Sunrise.

When Cassian Andor sat on that final beach with Jyn and held her as she held him, when he said her father would be proud of her and thought Maarva would be proud of me, he was doomed. When he first stepped onto our screens on the Ring of Kafrene, bearing trauma we still don’t comprehend, he was doomed. And yet, we loved him. We loved him so hard he got a TV show.

One of my last memories of Celebration Chicago is watching the Andor panel, snuggled up but feeling like death, and realizing, Wait, is this actually being made with care? Did I dare imagine one day loving it?

Burning out on a thing you love is different than burning out on a thing you do yourself. Reaching for the new episodes, the new books, digging your fingernails in and clinging to the characters you know you love. Their voices sound different in your mind’s ear. Why don’t you feel the same way when you see them laugh on the screen? Is it just me, or is it the shambling corpses I keep having to witness? I will not lie to you, dear reader: Book of Boba Fett broke something in me. Nothing important, of course; it was a Star Wars thing. I stopped understanding how it was possible to like Star Wars. It stopped existing to me, the little ship models on my desk were just shapes. This is all past tense of course, because as I write this, I am watching the Eye rise over Aldhani and it is beautiful. Andor shared something with me: the desire to care again.

Andor is beautiful. The entirety of the show, despite the weight of Star Wars bearing down on it, for Star Wars is many things, but it is rarely such consistent, masterful use of every single facet of film storytelling. Star Wars has never felt so grounded. Turns out shows don’t need to be dark and gritty to be real—they just need to tell stories about people. Empathy is the most real thing in the world. Without that, we get the Empire. Andor wants us to realize this fact, wants Cassian himself to realize it, because despite his best efforts, empathy bursts out of him, sparks from his chest, his deep care for his people nearly lighting him up. He acts a lone wolf but he goes back for people, and you can see the pain in his eyes when he realizes he can’t. We are blessed with a whole season of this. Of this sad man fighting so hard not to care, and failing miserably. He inspires.

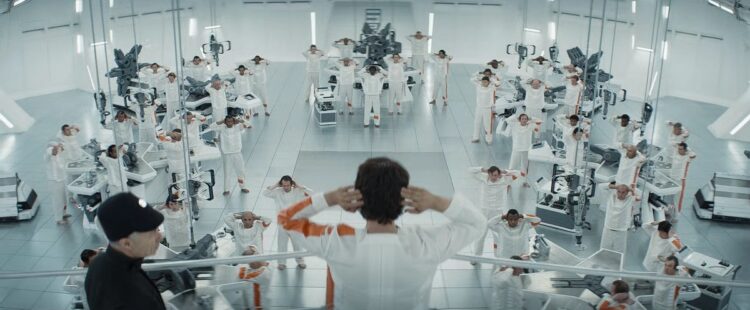

Where Boba Fett stumbled and gave up, Andor dove right in. The Dhani being driven from their homes, filmed in the Scottish Highlands, in parallel to the Highland Clearances. Narkina 5, science-fiction in style but far, far too factual in structure, is a bleak example of the realities of the prison industrial complex. If you can make anyone a criminal through law, and make the normal people scared of them, then you can do whatever you want with them once they’re in your system. Stripping them bare until there’s not even a human left. You can make your own automatons, if you’ve got a prison. I felt a lot of sick anger watching it all play out onscreen, in such a blunt admittance of the truth—our truth. This is what George Lucas was all about!

Perhaps because I have friends who work in prison abolition, this arc felt more real to me. Or maybe, hopefully, it felt as real to everyone else watching. I remember turning to my best friend as we watched Narkina and saying, “I hope this radicalizes at least one nerd.” I was astounded that my wish might even come true.

What a world it would be if Andor convinced enough people to listen, to really listen to what it is saying. Fascism is all around us. Capitalism is eating us alive. Prisons are stealing people and their lives for profit. Revolution, mutual care, networks, strong communities—those are the vital things. Also vital: the people themselves.

I’ve made my mind a sunless space. Cynicism. Realism. Optimism. What does Luthen see in his heart? A welcomed black, like home. Sometimes you have to burn everything out to get the job done. Sear away the empathy, if you can. Luthen is a realist, and the kind of man that is essential in revolution. In real revolution, the kind where people die and countries change. Hard choices must be made. Luthen is the kind of man to make them, because nobody else wants to. He willingly takes on this role, because he can do it. He will sacrifice completely, because he knows in his heart he is making a better future. He’s laying a path for Leia to one day hold Han’s hand in a forest and say “I do.”

I burn my life to make a sunrise that I know I’ll never see.

They become a chain of sacrifices, assuming Luthen burns away as he expects. Luthen to Cassian. Saw to Jyn. Tragic lineages. Their connections sprawl, spreading their meaning, transcending their bodies. Melshi, Chass na Chadic, even Cal Kestis. Never have I felt more like Star Wars is meaningfully connected. This is the Rebellion at its core, is it not? People who care. People who believe in a future. People who believe in the sun.

Andor is a blue sky, I thought to myself, gazing up into a rare break in the rain. It’s all grey and bleak and trapped within, but it wants you to think beyond that, above that.

The sky is rarely bright in Andor. Brief, vivid crystalline bursts in the dark taste like something more, sweet but short. The Eye watches victory and gives what it can. Niamos is a sunset dream for Cassian and Melshi after they escape Narkina 5. Cassian gazes into golden sunlight as a child, as an adult, and tries to feel something like hope. I’m not sure Andor is about hope, but it is nevertheless leading us to the understanding that beyond the smog, beyond the endless fascist monochrome, beyond the oppressive boots stomping down on your fingers, the sky remains as it always was: endless blue. Day will return; day has never left us.

Doesn’t that make you want to fight these bastards for real?

Just read this. Everything you say here feels like something I’ve said inside my own head at some point since watching Andor. It feels absurd to tear up reading an article about a Star Wars thing. Book of Boba Fett left me resigned that maybe Star Wars just wouldn’t be good anymore, and the Kenobi series was a dull nail in that coffin. So much so that I didn’t bother trying Andor until I began to hear notes of positivity about it.

It’s much the way I felt after leaving the theater in 2005; that maybe Star Wars and I would simply benefit from going our separate ways. It’s just a corporate franchise, though, so no big loss there. But it was a franchise that meant a lot to me growing up. Maybe it meant too much, but it got me reading the expanded universe novels, and then I fell in love with storytelling. And that led me to reading more and more until I was writing my own stories. I can never thank Star Wars enough for that, even if that never leads to a professional career in that arena.

So it is a solemn affair when I feel the need to shelve my Star Wars fandom, and there’ve been plenty of jumping-off points in the last decade. But Star Wars has never felt so personally meaningful as Andor has made it in my heart. The entire production-the writing, set design, costuming, the performances, the music-all of it feels like a miracle, not the least of which because of the relevant messaging and how it earns the moments which drive that message home, to say nothing of those footing the bill.

Anyway, I gush over this particular Star Wars thing ad nauseam. I just wanted to say that it’s comforting to hear another fan put into eloquence my own feelings on the thing. The show does feel radicalizing, and I go cautiously into that line of thought, politics being another thing I’ve frequently had to shelve for my personal mental health. But now I often wonder how many times I can run away to Niamos before reality catches up to me and no amount of privilege can protect me. That’s figurative, of course. Who can afford Niamos these days?