One thing that distanced Star Wars from other science fiction of its era was the aesthetic choice to make its universe feel truly lived-in, where many elements that would otherwise be fascinating and futuristic were shown full of dirt and dents, and treated as ordinary and utilitarian. We’re supposed to get the sense that the characters experience these things every day, and are not dazzled by ray guns, vehicles that defy gravity, or space travel. Most of the time, those are just set dressing, parts of the landscape, and not the focus of the story. And for that reason, painstaking attention was paid to the details of every set, prop, and matte painting to make sure everything looked believable, approaching the process more like a recreation of a historical period than a display of fantastical elements. This has had a surprising consequence: as I’ve observed several times, when you account for the technologies that exist in-universe, Star Wars tends to have better physics in its visual effects than other franchises with more science-abiding reputations.

When depicting an armed revolution against a tyrannical regime in this setting, making sure the non-fantastical elements still follow the laws of physics makes everything much more grounded, and the stakes more realistically felt. And in order to tell a story of hope in the face of insurmountable odds, where the enemy’s goal is to convince an entire galaxy that any attempt at resistance will only bring doom and overwhelming loss, being able to convey the full magnitude of the threat becomes essential. Directed by Gareth Edwards, known for his ability to imbue his films with a clear sense of scale, Rogue One was a magnificent achievement in this regard. Every time I have advocated for taking the physical implications and consequences of some plot device or visual element into account, and explained how it can actually enhance the storytelling, this is exactly what I’ve meant. Rogue One exceeded all my expectations, and they were already high.

The movie surprised me from the first shot, where we see planetary rings around Lah’mu that are comprised of very small particles like the majority of real ones are expected to be. After the big and non-uniform chunks we’d gotten around D’Qar the previous year, these were a more stable configuration and not something that would smash itself into fine particles or coalesce into a moon in a relatively short time. The shadows cast on the planet are impressive, too, with the blue color of the atmosphere gone from that region because there is no sunlight to disperse. After that, we get some more space environments with a variety that doesn’t look bad, either. There’s the Ring of Kafrene, an outpost constructed between two asteroids in what seems to be a very dusty star system or nebula. It could be unusual to have such a group of asteroids moving so slowly with respect to each other, which makes me worry about dangerous impacts, but for a civilization with artificial gravity and tractor beams it might not be difficult to maintain. Next, we have a view of Jedha from space, with subtle details like the location of the holy city at the center of an ancient impact crater, which perhaps had some influence on the concentration of kyber crystals there. Later, we visit Wobani, surrounded by wispy clouds of space dust, which would be moving past the planet at tens of kilometers per second at least, because not only do planets move at those speeds, but also any solar wind from the star that provides the light would push them away. But we see said clouds moving relative to the planet, so they get a pass.

However, where the approach really shines is in the depiction of the Death Star itself. With the camera centered first on a TIE fighter, moving on to a Star Destroyer in shadow, then finally to the station itself, the viewer can properly appreciate its immense size. The film also uses physics to convey the scale by depicting the final installation of its superlaser dish assembly on screen. Massive objects are very hard to stop once they are set in motion, and so, the huge piece of machinery spends almost two entire minutes of screentime being slowly moved into place. The Imperial Star Destroyer that hung as a symbol of oppression over the holy city of NiJedha is also given this treatment, very gradually accelerating after its engines begin pushing it away.

And then, the game-changing nature of the new superweapon is finally revealed. The first partial demonstration of its power starts with the station orbiting Jedha to get into position, in a trajectory that takes it between the sun and its target. The artificial eclipse faithfully recreates the visual appearance of real ones, with incredible aerial footage of one in 2016 available for the VFX teams to base their visualizations on. The effect of the shadow on the atmosphere is again properly calculated and shows how this temporary night is not absolute, as the air over lands beyond the horizon still remains sunlit. The resulting eerie lighting contributes to the sense of impending doom that permeates the scene.

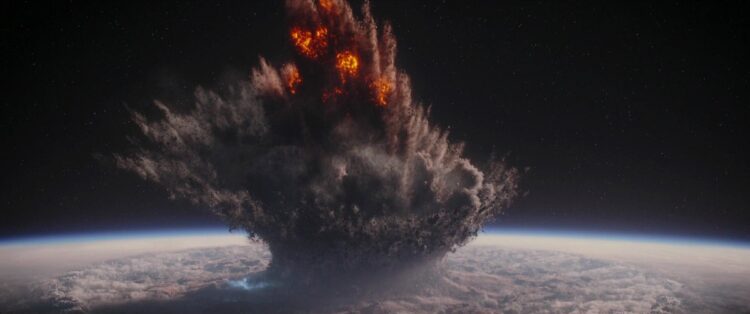

When the superlaser beam reaches Jedha, the amount of energy released is evident as the fireball engulfs the city in a fraction of a second, and condensation rings form between different atmospheric layers as the pressure wave starts to expand. The visuals are clearly inspired by footage of nuclear blasts, which is entirely appropriate given the historical parallels of such an event. And the sound design deserves praise too, as the sound in these shots is almost entirely muted, as if the camera is still far enough not to bear the brunt of the effects. Those we experience with Saw’s contingent, the sequence of their arrival determined also by physics. First there’s a groundquake, as shockwaves travel much faster in solid rock than through air. Then the air blast reaches the base and alerts them that something is very wrong, especially now that they can hear the loud roar of the explosion itself in the distance, joining the rumble of the ground tremors that also show no signs of stopping. Melted and vaporized rock glows in a reddish-orange color as it’s lifted up at the center of the explosion, and static electricity created by friction within the ash clouds produces lightning like we see in volcanic eruptions.

Meanwhile, a crater is forming as the force of the explosion pushes the bedrock away and the upper layers of crust get lifted and even folded onto themselves (something that also happened, for example, in Meteor Crater, Arizona). This is what nearly causes the death of our heroes, but luckily for them this takes a bit longer and they escape in time. But getting the characters so close to this wall of rock shows us how fast they actually needed to fly to overcome it, and when the camera is farther away it makes us appreciate the enormous scale of the cataclysm we are witnessing. When the view switches to space, the plume of ejected material seems almost static, but only because of its unimaginable size. By now it is hundreds of kilometers high, an altitude that fragments thrown at kilometers per second would take several minutes to reach. The tip is way beyond the atmosphere, with the plume actually projecting a shadow on the dusty air below, and the unobstructed view of the plume through the vacuum of space is clearer and more defined. Its structure also changes with height, showing billowing clouds of ash in the lower part where the atmosphere still provides some turbulence and convection, and straighter trajectories above where it’s so far from the surface that no air disturbs its path.

Depicting the physical consequences of what such a superweapon could do, and taking care to convey the massive scale of events, sells the despair in the characters’ faces as they ponder what they’ve just experienced. We can understand why the Empire would seem unstoppable after this. Why a single test shot can make Rebel Alliance councilmembers withdraw their support and decide to surrender. Because this is what the Death Star was designed for. The power to instill such fear that immediate capitulation seems the only course of action left. But above all, witnessing the horror that has been unleashed makes us feel the need to take every possible chance to ensure the battle station is destroyed. No matter how small. No matter the cost.

And so, our heroes go on an unsanctioned mission to the engineering archive at Scarif to get the Death Star’s structural plans. It won’t be easy, as the site is heavily fortified and an energy shield surrounds the entire planet. The visual appearance of this shield merits some comment, if only because, being used to photographs and timelapses from the International Space Station, it reminds me of the airglow our atmosphere has at a similar height. Since it is caused by ionized atoms and molecules, perhaps the shield over Scarif makes use of the natural ionosphere of the planet as part of its function. Or maybe the shield itself is causing extra ionization in the atmosphere and that makes it glow.

In any case, as events escalate and the Rebel fleet arrives, a space battle unfolds with spectacular visual effects on display. But even here, physics continues to play a role the plot in order to make things more interesting. When the shield gate needs to be destroyed to let the transmission with the Death Star plans go through, Admiral Raddus comes up with a plan to push a disabled Star Destroyer with a Hammerhead corvette. Again as before, as the small vessel starts to push, the bigger ship barely moves; but as it slowly acquires speed, inertia makes it harder and harder to stop. By the time it collides with the other Star Destroyer, the accumulated energy is such that it breaks the ship in half and makes it crash into the gate, ensuring the mission can succeed.

If you’ve read my last article, however, you might notice here that the space battle takes place very close to the planet and suspended above the Imperial base below, with no sign of the horizontal speed that would be needed to keep those ships in orbit. Here we must resort to the notion that repulsorlifts keep them aloft, even when disabled (but perhaps that’s a security measure, if Star Destroyers can hover above populated cities). And later, when explosions fling debris in all directions, it seems like their trajectories bend somewhat downward. So they at least added some gravity in the animations, even though a few pieces still remain floating. But a decade after Revenge of the Sith the audience is still mostly unfamiliar with orbital mechanics, so the scene can still feel grounded and realistic in spite of this.

However, these considerations are superseded by the sudden arrival of the Death Star, its immense size made clear as it rises behind the planet’s horizon as seen from space, entire atmospheric layers still small enough to only refract and distort a small portion of its full shape. Eager to stop the information leak and emerge victorious from a petty rivalry with Director Krennic, Grand Moff Tarkin quickly fires the superlaser and an explosion ravages the surface of another planetary body. This time, however, the target is a shallow sea and the humidity is much higher than in the cold desert of Jedha, so here the superheated steam and condensation cloud form a dense and complete sphere that glows from the fireball inside. As some of the Rebels escape with the plans that will keep hope alive in the galaxy, shockwaves and the laws of physics propagate on the planet below.

To say that I enjoyed this movie, released on the day I finished my PhD in Astrophysics, is an understatement. Not only were the themes, the characters and the story very compelling by themselves, but everything felt grounded and the visuals were truly spectacular. And the fact that such an accomplishment was achieved not just by avoiding unnecessary departures from actual physics but by actually embracing them and making them part of the story was the proverbial cherry on top.

Later Star Wars movies would take a more hands-free approach with the physics (although not as much as some people think), but in general, the visuals in those and in the live-action TV series tend to look more like NASA pictures than fantasy landscapes full of color. So much so, in fact, that sometimes I can even identify the original data they used for the work. And among the treats I’ve particularly enjoyed lately, I could list another good atmospheric re-entry, nice atmospheric maneuvering tricks using physics, and several others.

But I can’t finish this post without mentioning Andor, a show that expands on Rogue One in such a magnificent way that it deserves much more eloquent praise than I could give. It is the most grounded Star Wars has ever been, so much so that it could be translated to a modern-day Earth setting beat-for-beat without losing much of significance. It is for that reason, however, that when truly spectacular visuals are required for things that even the characters themselves find extraordinary, the result can be fascinating. Take the Eye of Aldhani, for example: an astronomical light show that needed to look so breathtaking as to not only be embedded in local culture but also make it credible that an Imperial installation would have minimal personnel indoors so most of them could enjoy the view. For this and the danger it posed in the skies, it played an integral role in the planned rebel heist, and therefore was an important part of the story. VFX teams assigned to the task received the infamous description “like nothing you’ve ever seen before”[1]Per Mohen Leo at the “Behind the Magic: The Visual Effects of Andor” panel at Star Wars Celebration Europe. but, given the nature of the show, it also had to look realistic (we even got Nemik enthusiastically explaining the science behind it, bless him). And oh, did they deliver. Both from the ground and within the phenomenon itself, the visuals were amazing and at the same time informed by real meteor showers and even reentries of space debris that can sometimes put on a good show.

Another notable use of physics in the series is Luthen’s battle against the Arrestor cruiser. Here it contributes to the tension when his ship is caught in the tractor beam, because his countermeasures will not work properly until the beam’s power is increased to a level at which they will be accelerated with enough force to destroy the projector dish. The battle was once again placed inside an atmosphere to improve the visuals (the Imperial officers’ black uniforms against a black sky would have posed a problem), but they didn’t limit themselves to that: when the TIE fighters explode, their lingering remains are white puffs of smoke with debris leaving downward trails. This is what would be expected at such heights, and more evidence of the high level of care put into each episode.

Rogue One and Andor are evidence that even in fantastical settings like the Galaxy Far, Far Away, science can be a great ally to storytelling rather than an antagonist to avoid. We must remember that science is the method we have to learn how reality works, so just as a good level of knowledge in history, psychology, and human culture will help the worldbuilding and characters feel more thoughtful and well-rounded, taking physics into account will contribute to the grounding and realism and make the threats feel more menacing. It can also result in even more beautiful visuals, and provide compelling and entertaining story points when its implications are actively embraced. And if the praise for Rogue One and Andor is any indication, this approach doesn’t seem to hurt. Wouldn’t you agree?

| ↑1 | Per Mohen Leo at the “Behind the Magic: The Visual Effects of Andor” panel at Star Wars Celebration Europe. |

|---|