In the concluding remarks of my previous piece about the physics of Concord Dawn, I argued that one could use science to think about how something unusual in a work of fiction might happen, and its consequences and implications, rather than just calling it a flaw that was not addressed and must be pointed out. After The Last Jedi‘s release, however, many chose this second option when faced with an element from the film’s opening sequence: bombers in space.

The argument generally goes like this: it makes no sense that Resistance bombers would attack a First Order Dreadnought by flying over it and dropping their bombs, since everything happens in space where there is no gravity, and therefore the scene was just filmed that way because that’s how bombers operate on Earth and it looks cool. Mind you, that might well be the actual reason! But since we’re thinking about physics, we could go a bit deeper than this and see where it takes us. One can’t invoke the planet’s gravity to explain bombs falling onto the Dreadnought, since the ship is not oriented with its ventral side directly facing D’Qar, although its artificial gravity seems to extend a bit beyond its topside hull (as seen when debris from explosions and destroyed TIE fighters fall towards it). There’s also artificial gravity inside the bomber, as an important plot point makes us painfully aware, and that alone could have propelled the bombs away. But it turns out that gravity was never necessary—according to TLJ’s Visual Dictionary, the bombs are launched from the bomber by electromagnetic means.

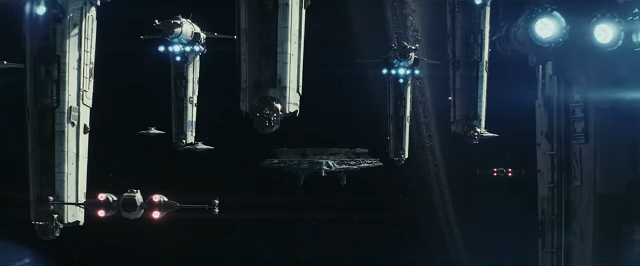

Airless aerial combat

Couldn’t the bombers, then, have attacked from any angle or launched the payload from a distance without making it look exactly like it would on Earth? Well, I guess they could, and we could dismiss the scene as unrealistic. But let’s think a bit more about it. Perhaps TIEs would have time to shoot at missiles or bombs if they came from further away, or tractor beams could be used to deflect them. Maybe by delivering them up close the bomber’s shields protect them for a longer time, and the bulk of the Dreadnought can be used as partial cover. But more importantly, this kind of bombing run in space is something we’ve seen in Star Wars since The Empire Strikes Back, and has also appeared in Rebels and Rogue One. A design that launches the explosives in a direction perpendicular to the flight path allows the ship to fly parallel to the surface of the target instead of directly at it, avoiding the need to reduce speed and change direction at the last moment. Also, as a planetary bombardment weapons platform, one would expect the ventral side of the Dreadnought to be better protected to withstand planetary defenses, so maybe the dorsal side was more vulnerable and reliant on anti-fighter batteries (destroyed by Poe). Perhaps the artificial gravity would repel the tiny bombs if released ‘upside-down’ on the ventral side. All of this leaves the sequence in the film as the best approach in those circumstances, even accounting for the physics.

Another common criticism of Star Wars spaceflight is that fighters would not be able to turn or maneuver with all their engines facing aft. I feel the need to point out that in many actual space launches, rockets change and adjust their trajectory with their main engines only, just by altering their throttle and orientation—and even some combat fighters use this technique. But even then, TLJ also shows Poe’s X-wing tracing a tight circle by pointing the nose inward and engines toward the outside of the curve, providing the necessary centripetal acceleration to do this maneuver in space. We also see an escape pod using maneuvering thrusters to orient itself, just like our actual spaceships do. So when one is ready to use physics to claim that something in a film is wrong, I would advise caution and making sure first that our assumptions are not too simplistic, lest the same arguments dismiss as impossible something our own technology does all the time.

After that, one should also be aware of how future technologies could circumvent these problems. The Last Jedi, with the First Order’s new hyperspace tracking abilities, provides a case of something that seemed impossible even for the characters living in that universe but turned out not to be anymore. The mind-numbingly high computer processing power needed for the task is now part of Snoke’s ship. Perhaps the huge size of this mega destroyer also allows for a wider distribution of sensors to track their prey even better. One can think of more implications of the achievement of a seemingly impossible feat rather than just dismiss it.

Forced extravehicular activities

The tracking of the Resistance fleet leads to an attack in which the bridge of the Raddus is destroyed and the crew expelled into space. But not long afterward, an unconscious Leia wakes up and uses telekinesis to go back to the safety of her ship, in urgent need of medical assistance. The scene raises some questions, but yes, hard vacuum is survivable for a short time, as Pablo Hidalgo clarified on Rebels Recon (they probably wanted to make sure we knew this for TLJ), and Leia stayed in space for less than two minutes, if I timed it correctly. When faced with such a vacuum the main problem by far is the lack of oxygen, which would make a human lose consciousness in about ten seconds and cause brain damage in a few minutes. Freezing to death, however, is not. It is in fact harder to lose body heat in the vacuum of space than on, say, Hoth’s surface, since you’re not in contact with a lot of molecules that would absorb that energy, and you can only cool down by emitting infrared light.

The frost on Leia’s skin could be a mistake, then (it’s a common misconception, after all). But in the spirit of this post, we can think deeper about alternative explanations. Something worth remembering is that liquid water isn’t stable in a vacuum, and will quickly turn into ice or vapor depending on the temperature. Exposed skin will cool down a bit because the evaporating water takes away some energy, but not enough to freeze. However, when the air that filled the bridge expands rapidly into space its temperature drops, and moisture condenses into droplets that might then become ice. Perhaps some ice particles were deposited on Leia’s skin, attracted by static electricity, and were in the process of evaporating when we saw her again.

But the dangers of vacuum exposure are many. The loss of pressure would make fluids leak into soft tissues, and gas in internal cavities and organs could expand causing damage. Nitrogen bubbles would form in the blood (like when a scuba diver ascends too fast), changes in pressure and oxygen concentration would make it hard for the heart to pump blood, and continuous release of water vapor from inside the lungs could cool them down too much and form ice inside the airways of the respiratory system. A very dangerous situation occurs when the person holds her breath before the rapid decompression, because expanding air would rupture the delicate tissue in the lungs.

However, one would assume that someone with decades of experience in a space-based military operations would have enough training to avoid this, plus Leia’s mental connection with Kylo at the time might have provided some warning. We also don’t know the amount of protection her instinctive use of the Force could have provided against the lack of pressure (the Force starts affecting ice and dust particles near her hand before she flies back to the cruiser, and her eyes are not bloodshot when she then opens them nor her skin swollen, for instance), and the rest of the damage could be accounted for by her unconsciousness and need of advanced medicine after the event. People also wonder why no air is sucked into space when they open the door for her. I thought about it myself until I noticed that the entrance to the bridge has two doors, which might act as an airlock. Plus there’s also the possibility of a security field retaining the air inside, of course.

Close encounters of the lightspeed kind

One of the climactic moments of the film arrives after the Resistance cruiser has been chased for many hours in deep space by a First Order fleet and the massive bulk of Snoke’s Supremacy, kept out of range by constantly accelerating, as evidenced by support ships falling behind when they run out of fuel (also, in an accelerating reference frame, the otherwise straight trajectories of the First Order’s barrage would turn into parabolas if they’re not fired exactly straight ahead, as we also see!). In a desperate maneuver to protect fleeing transports carrying what’s left of the entire Resistance, Vice Admiral Holdo decides to turn the cruiser around and engage the hyperdrive while aiming at the pursuing mega Star Destroyer.

After years of musing about the possible outcome of such a collision, and with a familiarity with the effects relativistic speeds can have on matter, I had resigned myself to disappointment when the eventual larger, but otherwise quite normal, explosion would appear on screen. So let me tell you up front, I can’t possibly overstate how delighted I was when I witnessed the visual display Rian Johnson had chosen for this event, only for my enthusiasm to go even higher when I read this article detailing the things they considered when developing the scene. The cruiser not only tears straight through Snoke’s ship due to its impossible speed, but an incredibly bright stream of particles and debris is created. The artists thought of the interactions that would take place at the atomic level and were inspired by actual physics experiments for the resulting look. Even the debris hitting smaller ships is still going so fast that it immediately tears them apart. The surreal visuals are motivated by massively underexposing the picture due to the extraordinary energies involved. And the whole scene is silent.

I am still in awe over how physics were used to enhance the visual impact and ‘cool factor’ of those shots, an approach I heartily support at every opportunity. But Star Wars is viewed by many as a franchise that never needs to adhere to known science when doing so would hinder the storytelling, with elements like sound in space pointed out as prime examples of how boring things would be otherwise. Although it is possible to depict silence in space without losing spectacle (and examples like Firefly, Planetes, Gravity or the subtle method used in the reimagined Battlestar Galactica come to mind), one can acknowledge the stylistic choice made for an audiovisual medium in this case. You can even imagine that we’re shown these scenes with sound but none was actually heard in the event (I believe every time a Star Wars novel has made a reference to sound in space was to point out the absence of it, with Cobalt Squadron the most recent example).

But in less clear examples of apparent scientific inaccuracy, there’s always a choice between two different paths for the viewer to take. One can lead to anger at storytellers for not respecting a set of rules, or even acceptance of the fantastical elements that will always underlie Star Wars. The other—trying to see how a scene could be justified within the bounds set by those rules—can lead to unexpected understanding, or even new threads of consequences to be followed later. If you really want to think about physics, this one is my personal favorite. There’s more fun to be found that way.

I haven’t read the whole article in detail, but thanks from a fellow physicist with admittedly odd pet peeves about physics in movies (depiction of sound in space is fine for me, but I dislike when characters on one ship have to be quiet to avoid detection by another ship).

One other thing that I noted in a review was that some of the weapons fire from the Supremacy has a noticeably arced trajectory.

Well, even then one could say that perhaps the enemy sensors are sensitive to anomalous vibrations on the target that would be produced by moving around or talking loudly (might be weird, but still).

And the arced trajectories are addressed in this article! I think it could be the result of the accelerated frame of reference the ships are in 🙂

Thanks for the comment!

I like to think it’s just an instinctive reaction—like Needa ducking when the Falcon buzzes his bridge—rather than something with a rational basis.

Also, by being quiet and listening intently you might notice if you forgot to turn something off that could be detectable by sensors 😛

This is a fun article! I have to admit that fidelity to real-world physics is not high on my list of priorities for Star Wars movies. With things like sound in space and starfighters banking during maneuvers, the space bombing sequence didn’t really bother me – in fact, I thought it was a nice nod to the Second World War, the inspiration for so much of the original Star Wars’ sequences. Still, thinking through plausible explanations for various phenomena can be a fun exercise.

Internal narrative inconsistencies bother me more than any notional relationship to physics – hyperdrive ramming bothers me because it is so noticeably inconsistent with the tactics in previous movies. As you say, though, it was a cool looking sequence!

Thanks! I have to say, Star Wars is a big part of what drove me to become an astrophysicist, so I’ve always loved thinking about the science in it. There are many ways to enjoy this saga, indeed!

However, I don’t see why so many are finding Holdo’s maneuver to be such a big inconsistency. I don’t think there is one… The Death Star was too big for the maneuver to work against it effectively with the Rebellion’s starfighters, the escape at Hoth was about saving the lives of the people evacuating so it wouldn’t make sense to sacrifice them like that against star destroyers, at Endor we again have the problem of how large the Death Star is (plus there’s the Imperial fleet, the planetary shield, etc.). I think Chuck Wendig put it succintly on Twitter today: https://twitter.com/ChuckWendig/status/951087462134272001

But whatever the reason, my answer for apparent internal narrative inconsistencies could be the same as for apparent scientific inaccuracies: if you take them as facts you can learn from them about their universe by thinking more deeply about their implications. Because perhaps they weren’t inconsistencies to begin with… (Have you read “From A Certain Point Of View”? It contains a lot of extra info that turns many apparent inconsistencies from A New Hope into logical outcomes just by adding extra info that wasn’t vital for the original story. It’s a fun exercise)

It’s not a problem on the level that ruins my enjoyment of the movie, so I’d distance myself from the trolls on Wendig’s Twitter who claim it somehow ruins the movie or the franchise. The ramming sequence is undeniably cool, and it serves a perfectly valid narrative contrivance. Furthermore, there are any number of reasons we could imagine for why ramming works in this moment and not in others (the “Raddus” has unique advanced shields that make it work; DJ’s hacking compromised the “Supremacy’s” shields somehow; Holdo is a mathematical super-genius capable of plotting such a precise course, where no one else could; etc.). In the end, not knowing which of these reasons (or which combination) is “correct” doesn’t really matter all that much – it’s a cool sequence in a pretty cool movie.

Of course, there’s one very obvious and very valid reason why we don’t see hyperdrive ramming all the time: the audience likes Star Destroyers, and X-wings, and laser cannons, and proton torpedoes. Star Wars has a very cool visual-auditory aesthetic for combat, which is deeply meshed in the military capabilities of the Second World War, but with lasers. The hyperdrive ramming sequence in VIII is also really cool, but it exists outside of this aesthetic (in a way that the flash-zap Hoth Ion Cannon does not). Similarly, the Death Star or Starkiller serve as challenges to that aesthetic, acting more like a nuclear weapon than a WWII artillery piece. However, the movies also hang their hat on that distinction, by explaining that the Death Stars and Starkiller are sudden technological breakthroughs that have altered previous modes of warfare. Inconsistency in this sense is not actually a bad thing – it can be deployed for especially dramatic moments. Like the Death Stars and Starkiller, ramming works well as a dramatic one-off rare event, but given how alien it is to the previous aesthetic I think it deserves at least some explanation. The movie seems aware of this in some cases – a few brief moments are spent justifying how the First Order could track ships through hyperspace (through a major technological breakthrough). Clearly not everyone in the audience needed this sort of context for the dramatically inconsistent aesthetic of hyperdrive ramming. On the other hand, from what I’ve read it seems like a good portion of the audience would have preferred some explanation for this inconsistency, whatever the explanation would be. I doubt such an explanation would have detracted from the movie; therefore, it seems like some sort of context would have been a wise narrative choice.

That’s the narrative side of the debate. However, Star Wars is a major influence on my interest in political and military history. For kicks, feel like providing at least some response to Wendig’s attempt at an in-universe explanation, which is totally nonsensical. No, the US Navy doesn’t ram destroyers into aircraft carriers, mostly because we have better alternatives for sinking warships. Adversaries who don’t have better alternatives, however, definitely seek asymmetric ramming attacks (a la USS Cole, or the IRGC’s preparations for explosive collisions in the Persian Gulf). Similarly, we do not regularly resort to air-to-surface ramming, again because we have better alternatives. Adversaries who don’t have better alternatives definitely seek asymmetric aerial ramming attacks (Japan’s kamikazes are the most famous example). More to the point, however, we *do* sink warships by ramming unmanned aircraft (missiles) into them. The invention of missiles in turn had a major feedback into how warships are designed. We don’t build battleships anymore, because naval gunfire has been reduced to a supporting role for shore bombardment and point defense. Most of our surface combatants are instead armed with missiles to shoot down other missiles. In fact, there is an ongoing debate about whether we should build aircraft carriers anymore, because contemporary missile technology leaves expensive carriers extremely vulnerable to swarms of very cheap anti-ship missiles (a la theorists like Wayne Hughes). All of this is to say: if hyperdrive ramming is possible, it is not unreasonable to assume that people to use it, *a lot.* Again, a brief explanation for why this isn’t the case might have been nice.