One thing that distanced Star Wars from other science fiction of its era was the aesthetic choice to make its universe feel truly lived-in, where many elements that would otherwise be fascinating and futuristic were shown full of dirt and dents, and treated as ordinary and utilitarian. We’re supposed to get the sense that the characters experience these things every day, and are not dazzled by ray guns, vehicles that defy gravity, or space travel. Most of the time, those are just set dressing, parts of the landscape, and not the focus of the story. And for that reason, painstaking attention was paid to the details of every set, prop, and matte painting to make sure everything looked believable, approaching the process more like a recreation of a historical period than a display of fantastical elements. This has had a surprising consequence: as I’ve observed several times, when you account for the technologies that exist in-universe, Star Wars tends to have better physics in its visual effects than other franchises with more science-abiding reputations.

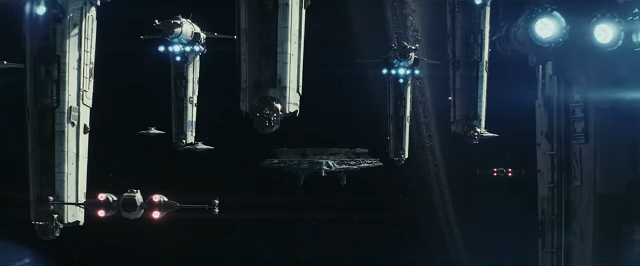

When depicting an armed revolution against a tyrannical regime in this setting, making sure the non-fantastical elements still follow the laws of physics makes everything much more grounded, and the stakes more realistically felt. And in order to tell a story of hope in the face of insurmountable odds, where the enemy’s goal is to convince an entire galaxy that any attempt at resistance will only bring doom and overwhelming loss, being able to convey the full magnitude of the threat becomes essential. Directed by Gareth Edwards, known for his ability to imbue his films with a clear sense of scale, Rogue One was a magnificent achievement in this regard. Every time I have advocated for taking the physical implications and consequences of some plot device or visual element into account, and explained how it can actually enhance the storytelling, this is exactly what I’ve meant. Rogue One exceeded all my expectations, and they were already high.

Read More