I would love to say that it began with the second article I wrote for Eleven-ThirtyEight. I would love to say that it began with From a Certain Point of View. I love to say that “The Baptist” was our first aromantic and asexual representation in Star Wars. Though Omi is as alien as you could get – the dianoga of the trash compactor in A New Hope – the manner in which Nnedi Okorafor wrote her and her sexuality is dignified. Noble, even.

Unfortunately, the novel Phasma beat “The Baptist” to publication by little over a month. Within the novel, Phasma was described as never having been interested in relationships with men or women. It would be frustrating enough that our first aro/ace character was a villain, as a common microaggression against aro and ace people is interpreting our lack of attraction as a lack of compassion. But there were ways that this could have still worked. There are ways to make aro/ace villains that are compelling. What makes Phasma sting as our first aro/ace coding in Star Wars canon[1]Any potential aro/ace coding in Legends is another discussion. is the fact that the novel leans into that microaggression.

This lack of relationships is noted within the context of someone reflecting on how much crueler and more ruthless Phasma is, specifically in contrast to sympathetic characters who have partners. While I presume that author Delilah S. Dawson did not intend to say that Phasma is immoral because she is aro/ace, the framing nevertheless sends that message.

An inauspicious beginning for our representation. But far, far from the end.

Over the six years I’ve been writing for Eleven-ThirtyEight, many of my articles have focused on exploring aromantic and asexual representation and coding within Star Wars. We have come a long way over those years, and as the site closes its doors, this – my final article – will look back on the journey and ahead to new frontiers.

This Is What Asexual Looks Like

While Phasma and Omi were our first aro/ace-coded characters, the first official confirmation of asexuality would come two years later, in Dawson’s other novel Galaxy’s Edge: Black Spire. Vi Moradi, who made her debut in Phasma, was implied to be both aromantic and asexual in Black Spire, and then confirmed as asexual by Dawson and editor Elizabeth Schaefer.

Vi is incredible. One of my favorite characters. It’s a night and day difference between her and Phasma’s queer coding, to the point that it almost feels like a course correction by Dawson regarding asexuality (and implied aromanticism). A correction I appreciate.

However, Black Spire stumbles in regards to intersectionality. Fans of color noted the novel was very much in need of sensitivity readers regarding race. And I am not here to give any excuses for racist writing, regardless of intention. That is not my place; I am not one of those harmed by the portrayal. Nevertheless, I cannot sweep Vi under the rug. I cannot ignore that our first official aro/ace character was a Black woman.

Women of color, especially Black women, tend to be hypersexualized. It is one of the ways that Black people have been dehumanized, and white supremacy rationalized, over the long history of racism. Today, one of the most prominent aro and ace activists – Yasmin Benoit – is frequently harassed for being “too sexual.” There is an automatic objectification of her due to the color of her skin.

Her hashtag – #ThisIsWhatAsexualLooksLike – is both a statement that clothing is not an invitation and a declaration that Black people specifically belong in the asexual community. Asexuality is unfortunately seen as a “white” orientation, which only serves to compound the usual racism that seeps into every part of our society. Benoit – like many other aro and ace activists of color[2]Other activists and scholars of color to follow include Tyger Songbird, The Ace Couple podcast, Sherronda J. Brown (Wear Your Voice, Scalawag, Refusing Compulsory Sexuality), Justin Ancheta, Marshall … Continue reading – has had an uphill battle to find a space for herself, specifically because of racism.

Therefore, while Black Spire falls short, it would be a grave mistake to dismiss Vi Moradi as The Milestone™ of aro/ace representation in Star Wars that she is. The first aromantic and asexual character in Star Wars is Black. That is worth celebrating.

As we look to the future of aro/ace representation in Star Wars, there are two thoughts I have.

The first is that Vi has seemed to fade a little from the forefront of Star Wars. The initial face of Galaxy’s Edge, played by Alex Marshall, Vi used to be a very visible character, frequently promoted by Lucasfilm even outside the park. I do not think her queerness has much to do this fading; she did get a Pride Variant cover in 2022. Rather, this is likely a combination of marketing cycles and racism, as characters of color are more easily sidelined.

As Lucasfilm seems to be setting their sights again on the era of the sequel trilogy, it would be good to see Vi again. And it would be critical to see Vi in a new story that respects the intersection of Black representation as well.

Secondly, not only is Vi the first aro/ace character of color, she’s also the only aro/ace character of color. The characters we’ve had since have been either aliens or white. Not only do we need more aromantic and more asexual characters in Star Wars’ future, we need to see more intersectionality within those characters.

I Wish There Was a Simple Word

One of the barriers to queer representation in Star Wars is that our terms for these identities are not canon. Aromantic, asexual, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, etc. These do not exist as terminology within the Galaxy Far, Far Away. Which is why a lot of these identities are expressed through relationships, pronouns, or a character’s musings, and then confirmed in the meta.

The team writing the Doctor Aphra comics clarified that she was specifically a lesbian in an interview, and StarWars.com used “asexual” in Leox’s bio. The closest we’ve gotten to an in-text use of our own words was “transcended gender” for the clone Sister in Queen’s Hope.

There’s always going to be a dance between identity and language when it comes to queer representation. And this is especially true when it comes to identities under the aro and ace spectrums. We don’t have the same easy queer shorthands of pronouns or a kiss shared between people of the same gender. A lack of overt interest will result in the default assumption of “not having met the right person”, and any intimate interest will result in the default assumption of romance and sex.

Genuine effort has to be made to show the queerness of an aro or ace character. With the likes of Phasma and Vi, queerness was shown by pointing out the lack of attraction. Phasma’s lack of relationships is noted. Vi rejects an advance by saying she’s not into it.

“We’re partners. I care for you, but not like that.” She’d never cared for anyone like that, men or women, never had such urges. (…) “Look, just know that I’m your friend, and I’m here for you. Not romantically or physically, but for pretty much anything else. You can count on me. Okay?”

This is also how we get queer coding for Obi-Wan Kenobi in Padawan by Kiersten White. Obi-Wan ponders how he doesn’t experience attraction in the same way as his peers, something shared by Vernestra Rwoh of The High Republic. In Out of the Shadows by Justina Ireland, Vernestra watches the awkwardness of two exes, reflecting how those specific emotions were foreign to her.

Vernestra sighed. This was a difficult conversation for her because she’d never once had any of those feelings, regardless of the people she met. She could tell when someone was attractive, and there were people she liked more than others, but she never felt the push/pull of attraction so many other Padawans did when they came of age.

Noting the lack of attraction is the quickest way to signal aromanticism and asexuality. If the default assumption is that romantic and sexual attraction exists, then declaring their absence is critical. And the way that we get to see it from within Vi, Obi-Wan, and Vernestra – the way we get to see the characters put words to their experiences – personalizes the feeling. It lets people find parts of themselves within the description.

I especially think of the teenagers who don’t know the words “aromantic” or “asexual”, who feel broken and alien among their peers like I did, well into my adulthood. Even if they aren’t given the exact terminology, they are still given a place where their experiences are voiced. They can point to these passages and say “This is me. I’m not alone.”

The other way that we’ve seen aromanticism and asexuality discussed in Star Wars has not been through lack but through wholeness.

I have already waxed poetic about how “The Baptist” with Omi the dianoga made me feel whole as someone who was then navigating the world as a woman. (Hi, in case you missed it, I’m trans and a man). You won’t find the words “asexual” or “aromantic” in that article – I was still testing the waters here at Eleven-ThirtyEight – but it’s exactly what I was referring to. Much of Omi’s internal dialogue is about finding herself to be complete, without a mate.

It’s very similar to how Leox Gyasi describes his asexuality. Rogue Podron, in their review of Into the Dark by Claudia Gray, were one of the first to point out this framing. Leox’s speech isn’t about him missing out on anything, but rather having his own life to live. Sex just isn’t a part of that.

I relish the knowledge that I am the ultimate fulfillment of my ancestral line, the point to which all their striving led.

I do not know if Okorafor meant for Omi to reflect an aromantic or asexual identity, or if Gray knew about the 1972 “Asexual Manifesto” by Lisa Orlando, but that sense of wholeness is one of the ways that asexual and aromantic activists frame their orientations.

“Asexual,” as we use it does not mean “without sex” but “relating sexually to no one.” Asexuality is, simply, self-contained sexuality.

There are differences between Orlando’s manifesto and how we understand asexuality today, but this portion still rings true. Scholar Sherronda J. Brown quotes this early in their book Refusing Compulsory Sexuality: A Black Asexual Lens on Our Sex-Obsessed Culture. They use Orlando’s framework to define asexuality not as the lack of an expected human experience, but a complete human experience unto itself.

While these citations specifically come from an asexual perspective, the sentiment applies to aromanticism as well. Dawn, a Star Wars fan on the aromantic spectrum (the gray-romantic label fitting them best), had a similar response to another moment of aro/ace coding:

It’s just so cool because it describes what the relationship IS instead of what it isn’t. Aro identities are of course often framed or indicated by what they are not and not for the profound type of love that they can be. Took me a bit to realize that’s why it hit me so hard.

The relationship that Dawn is referring to here is that of Maz Kanata and Dexter Jettster.

Oh joy of joys, this is the best gift of representation. I get to genuinely use Dexter Jettster as an example in an aroace article? Happy Belated Pride Month to me.

I have already gone into a close read of this moment from The High Republic Adventures (Phase II) written by Daniel José Older.[3]Artists Toni Bruno, Harvey Tolibao, Michel Atiyeh, and letterers Tyler Smith and Jimmy Betancourt. To summarize: this is a very aromantic and queerplatonic thing for Dex to say. The coding is strong here.

Beyond my own personal love for the character, this is a significant milestone in aro/ace representation for Star Wars. Because the coding specifically leans towards and leads with aromanticism.

For our other characters, aromanticism is assumed to be an element of their asexuality. Overlap does exist; I myself am aroace. But it does a disservice to both identities to presume they always come as a package deal. It limits the expression of asexuality in ace people, and it diminishes the importance that aromanticism has to aro people.

“Asexual people still want romance” can be and has been used as an advocacy tool to showcase the wide range of people under the ace umbrella, but it also has been used as a way to downplay aromanticism to make asexuality more “palatable”. Be it for people who are only aromantic or for the aro side of aroace experiences, our aromantic identities often get ignored or painted as unfeeling.

Much like Phasma, if we cannot feel romantic love, then what cruelties might we be capable of?

As a result, Dex putting aromantic coding at the forefront of his experience, not grouped with an asexual revelation, is a level of recognition that aromanticism has not yet had in Star Wars and rarely gets in general.

This is the takeaway that I want for future aro/ace representation. Not having the words “aromantic” or “asexual” to use in the Star Wars canon has resulted in several beautiful, poetic descriptions of our experiences. However, there are still ways to acknowledge aro and ace as separate identities. I want aromanticism and asexuality to both be honored as whole in their own right.

Satine’s Shadow

We have not heard mention of a certain Duchess since Obi-Wan was implied to be aromantic and asexual. The last we hear from her and of her was in Brotherhood by Mike Chen, which was released two and a half months before Padawan.

As a fan of Satine, it’s odd. As a fan of aroace Obi-Wan, it’s hilarious. As both, a question tends to linger in the air.

Whenever we do get around to their youthful meeting, how queer is it going to be? Padawan opened the door to explore an aro, ace, or queerplatonic relationship. But will Lucasfilm care to follow through?

It’s pointless to speculate, but to rehash a point above: unless care is taken to verbalize the spectrums of aromanticism and asexuality, the default read on Obi-Wan and Satine will be a heterosexual romance.

Take for example, the relationship between Axel and Gella in Convergence by Zoraida Córdova and Cataclysm by Lydia Kang. These two – a young man and a young woman – are shown to form a close emotional bond that is never described as romantic within either book. Yet fandom has still defaulted to that interpretation.

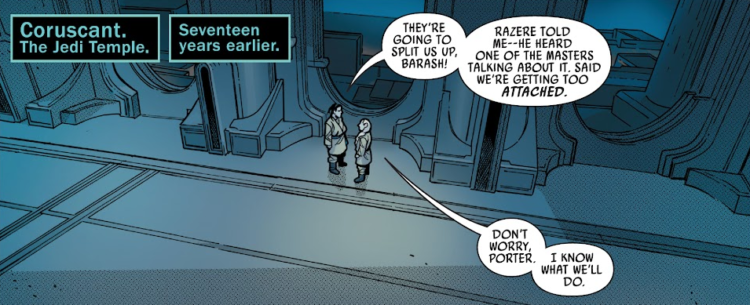

Fortunately, The High Republic also gave us another close emotional bond between a young man and woman that fandom has openly accepted as platonic. For Porter Engle and Barash Silvain of The Blade, written by Charles Soule,[4]Artists Marco Castiello, Jethro Morales, Jim Charalampidis, Jim Campbell, and letterer Travis Lanham. their relationship is treated as the same level of “taboo” within the Jedi Order that is usually reserved for romance and sex. There are even shades of secrecy and deception that reflect Anakin and Padmé’s relationship. Porter and Barash’s platonic attachment to each other is as compromising as a romantic couple’s.

Though it may not be the most healthy attachment (though certainly leagues more so than Anakin and Padmé’s), framing Porter and Barash in this manner is still significant. It’s acknowledging that a platonic bond between two people isn’t a lesser commitment than a romantic or sexual one.

But how did Porter and Barash beat the odds and avoid a widespread interpretation of romance within their relationship? By claiming each other as “Brother” and “Sister.”

This is where my feelings about it get complicated.

For clarity, I love that Soule chose to have Porter and Barash explicitly adopt each other as siblings. It was a short comic run (only four issues), and it was the best shorthand to lock in their relationship as platonic. In this instance, it’s a beautiful decision.

However, it does fall into a pattern within fiction, where characters are given reasons why they wouldn’t be romantically involved. Be it adoptive or biological, family automatically puts romance and sex out of bounds (Splinter of the Mind’s Eye does not count). As a result, it can feed into a sort of relationship hierarchy, where a platonic relationship has to “graduate” to either family or romance. Within this pattern, a platonic relationship doesn’t count as intimacy on its own.

NOT ONLY do i want more m/f [male/female] friendships in media where there’s nothing romantic between them, but i want m/f friendships where both characters are SINGLE so that there’s no reason there to “justify” why those two can’t date. i want the platonicness of their relationship to be something that stands on its own merit.

Tumblr user yardsards

This is how Dexter Jettster ends up being a major queer milestone again. There’s no reason for him and Maz to not be in a romantic or sexual relationship. There’s no justification for why they can’t say they’re dating. The option is fully open to them, it’s just not for them. There’s neither barrier nor obligation to claim it. They’re each other’s people. That’s all they need to be.

For future aro/ace representation, I’d of course love to see Obi-Wan and Satine be coded even more as an aro/ace couple. But I wouldn’t necessarily spend my energy pushing for that specific outcome.

Instead, I would like there to be intimacy shown and celebrated through platonic commitment. I would like to see more explicitly platonic, explicitly queerplatonic, explicitly aromantic, explicitly asexual relationships shown to be as deep and galaxy-shaping as romance and family.

Next Steps Into a Larger World

Where we are now is beyond anything I could have imagined when I first wrote about Omi. Even with all the implications of Phasma, it was at least a start. Effort was made. If it had ended there, we’d be having a different discussion. Within the context of the growth since, including the course correction with Vi, it can be seen and acknowledged as the shaky first steps. The initial ground broken. And since then, we have seen a beautiful growth in both explicit and coded depictions of aromanticism and asexuality.

Nevertheless, there’s still more work to be done. The intersection with race still needs major course correction itself, and there are countless other intersections of representation that I have not touched on within this article.

Aromanticism and asexuality themselves still need to be acknowledged as unique and given equal honor. Within each of those identities, there are spectrums of attraction and desires, a kaleidoscope of experiences worth exploring. We are not all aroace, and even the aroace experience differs from person to person.

Furthermore, as these identities tend to be minimized in our world, Star Wars has a chance to give us a vision of a better world. One in which aromantic and asexual people and relationships can carry the same level of impact as romantic or familial connections.

The foundation has been set; it’s time to build.

It has been an honor to speak on aromanticism and asexualty for the past six years. Thank you, Cooper, for giving me this platform, and thank you to everyone who clicked and read with an open mind. Let’s see where we get to go next.

| ↑1 | Any potential aro/ace coding in Legends is another discussion. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Other activists and scholars of color to follow include Tyger Songbird, The Ace Couple podcast, Sherronda J. Brown (Wear Your Voice, Scalawag, Refusing Compulsory Sexuality), Justin Ancheta, Marshall John Blount, Angela Chen (ACE: What Asexuality Reveals About Desire, Society, and the Meaning of Sex) |

| ↑3 | Artists Toni Bruno, Harvey Tolibao, Michel Atiyeh, and letterers Tyler Smith and Jimmy Betancourt. |

| ↑4 | Artists Marco Castiello, Jethro Morales, Jim Charalampidis, Jim Campbell, and letterer Travis Lanham. |

One thought to “The Point to Which Their Striving Leads – The Journey of Aromanticism and Asexuality in Star Wars”

Comments are closed.