In 2002, we were blessed with a scoundrel of a space cook with an arm gimmick, a ready grin, and a menacing chuckle. Dexter Jettster – the one-scene wonder of Jedi Quest #2: The Trail of the Jedi.

Oh, and also of some movie, I suppose.

While created and developed for Attack of the Clones, the Besalisk actually debuted in Legends literature. His first appearance came a month and a half before the film’s release, in Jude Watson’s middle-grade series Jedi Quest. Though the movie would obviously make a bigger impact, this pulp-fiction book set the stage for how Dex would grow into a more complex character: through literature.

Over the course of the Legends Expanded Universe, Dex would make enough scattered appearances across novels, comics, and magazines that certain character traits began taking root outside of the movie. Traits that held a distinct similarity to a literary classic.

In 2002, we were blessed with another scoundrel of a space cook with an arm gimmick, a ready grin, and a menacing chuckle. Long John Silver – the villain of Disney’s Treasure Planet.

Oh, and also of some novel, I suppose.

This animated film was yet another entry in a long, long line of Treasure Island retellings. Within Robert Louis Stevenson’s novel, Long John Silver portrayed a deliberate duality. Using the mask of a friendly cook to earn the heroes’ trust, Silver was in fact a pirate captain scheming to seize the titular treasure from under their noses. So memorable was this villain that he would end up shaping the way pirates are portrayed in fiction from his debut in the 1880s all the way to today.

Even the juggernaut that is Star Wars is not immune to his influence. There is an easy comparison to be made with Hondo Ohnaka, and the writers of Solo: A Star Wars Story directly pulled from Treasure Island and Silver to form the dynamic between Tobias Beckett and Han Solo. And while a less overt reflection than Hondo and Beckett, Dex nevertheless ended up developing the pirate’s iconic duality. Through the lens of Long John Silver, the complexity of Dexter Jettster comes into sharp focus.

In 2012, unfortunately, the traits that comprised said complexity would technically be decanonized with the Disney purchase. Dex was thereby reverted from the complex literary character he had become back into the one-scene wonder of the movies. We would have to wait for new storytellers to come in and rebuild.

Dex appearances after the purchase of Lucasfilm were rare for a time, though not without significance. We had our most intimate look at Dex in The Smuggler’s Guide by Dan Wallace in 2018, and other works could be cross-referenced with Legends to infer meaning. But it wasn’t until the twentieth anniversary of Attack of the Clones that we received solid confirmation that Dexter’s old literary traits had taken root in the new canon.

For a full third of 2022, Lucasfilm released new and substantial Dexter Jettster content in monthly installments: Queen’s Hope by E.K. Johnston in April, Brotherhood by Mike Chen in May, Star Wars Insider #211’s “Inheritance” by George Mann in June, and Padawan by Kiersten White in July.

His appearances ranged from cameo to significant player to main character, but one thing mattered across the board: the literary character of Dexter Jettster was back.

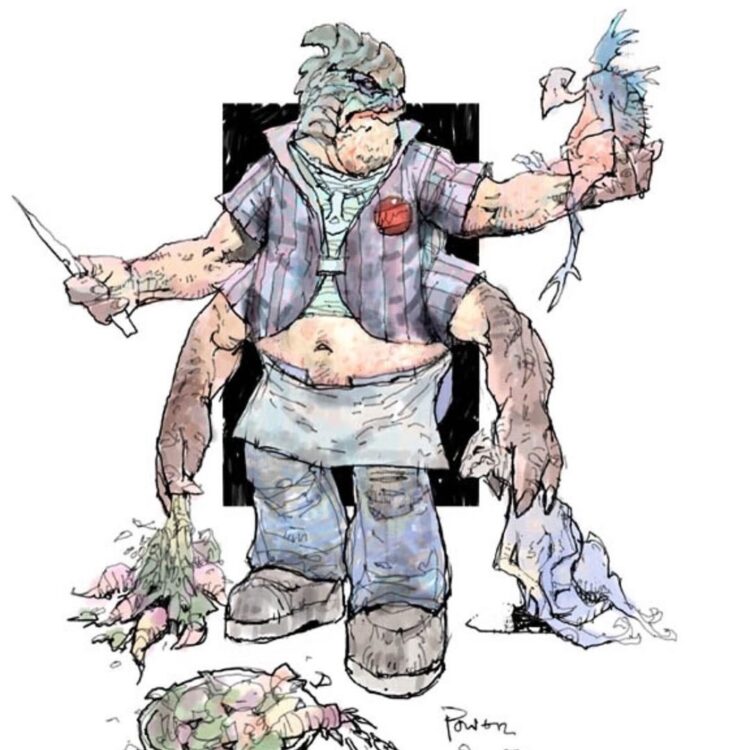

By the Looks of Him

Before we dive into our literary analysis, we do have to pause for a moment to discuss the way Dex is written. In particular, there are significant differences between the portrayal of Dex in Jude Watson’s Jedi Quest and in almost every other portrayal of Dex throughout all of Star Wars. Yes, its release prior to the film could have played a factor in this difference, but we still have to talk about fatphobia.

Fatphobia is bias and discrimination against fat people. In the real world, this has existed for centuries and continues to cause harm to this day. In the media, this bias is reflected and furthered by making a character fat as a shorthand for immorality.

Even with fat characters we are supposed to love, authors will still make jokes about their size or describe them with othering language. These fat characters aren’t allowed to just exist in their bodies without judgment. This happens with Dexter Jettster as well.

The Jedi Quest series mentions Dex’s size so much that it feels like the core of his personality, a personality which is wildly different from any of his other portrayals.

Here, Dex lacks his usual guile, his motives feel laced ever so slightly with greed, and it feels like Obi-Wan and Anakin are constantly annoyed with him. A perfect encapsulation of this occurs in the ninth book, The False Peace, when the two Jedi go to his diner for intel during an investigation. Dex prattles on about his food as Obi-Wan tries to cordon him back to the topic at hand. The most critical piece of information that Dex gives them ends up being accidental, as he boasts about a bribe he took from the in-disguise antagonist.

“A journalist for the Holonet news even paid me to keep her airspeeder out back… I said yes because she was a looker – or maybe it was the credits she put in my hand, ha!”

The entire interaction is permeated with othering language that Watson uses to describe Dex’s body. The Besalisk isn’t allowed to just sit or point or walk. Every physical action is accompanied by judgment being passed on his size.

And since Jedi Quest has this obsession with describing Dex’s size, it sends the message that his obliviousness, his greed, and his obnoxiousness – all unique to this version of Dex – are tied to the shape of his body.

Jedi Quest is far from being the only Star Wars media that displays fatphobia [1]Thank you to Meg Humphrey of Rogue Podron for sensitivity reading on the extended discussion of fatphobia at the link, a portion of which was reused here.. If you’re consuming Dexter Jettster content, it’s pretty much inescapable. Even the best appearances of him will have casual fatphobia sprinkled throughout. For example, Brotherhood, an otherwise revelatory portrayal of Dex, still describes him as having to squeeze through the double doors of his kitchen and then pokes fun at his eating habits.

However, Jedi Quest is still unique in that fatphobia affected not just the physical depiction of Dex, but the depiction of his personality and capabilities as well. Intentionally or otherwise, this series linked being fat with a failure of character. I would be remiss if I failed to acknowledge this element in my analysis of Dexter Jettster’s portrayal over the years.

Moving forward in this essay, I will be taking a Death of the Author stance not only with Jedi Quest and Dex’s portrayal therein, but with all Dexter Jettster’s appearances in Legends and canon. By that, I mean I will be ignoring what each author – Watson included – may or may not have meant or known about each other’s work when writing Dex.

I will instead be examining the various appearances of Dexter Jettster as if they are a coherent character study, regardless of author intention. The exceptions made to this are my acknowledgement of the break between Legends and Disney canon and the stories that are outside of both (i.e. Detours and other parodies, and appearances in non-canon games) which will not be examined here.

This all established, let’s start where Dexter Jettster’s complexity first appears in Legends: right at the beginning, with Jedi Quest and Attack of the Clones.

Respect for the Difference

In Jedi Quest, Dexter Jettster is a jovial business owner, chuckling away at his own jokes, and seemingly baffled by Obi-Wan Kenobi’s information requests.

In Attack of the Clones – the movie, the script, the comic and novel adaptations – Dexter Jettster is a level-headed, keen-eyed informant who rivals even the Jedi Archives’ knowledge.

If we are treating both of these as accurate portrayals of the same character, not too far apart in the timeline, then what is the deciding factor in the change?

Trust.

In Jedi Quest, Obi-Wan and Dex do not know each other. Obi-Wan explicitly says that he does not trust Dex, and he keeps the diner owner from getting too close to Jedi business. And while Dex goes on about how much he considers Obi-Wan a friend, other Legends material explicitly shows that the friendly cook is a deliberate act. A strategy to keep those he mistrusts from seeing the cunning scoundrel he actually is.

For examples, we have to head forward to 2006-2008, to Dex’s appearances in The Life and Legend of Obi-Wan Kenobi by Ryder Windham, Wild Space by Karen Miller, and Jude Watson’s follow-up series to Jedi Quest, The Last of the Jedi.

Unlike the disconnect between Jedi Quest and Attack of the Clones – where we have to leap from one story to another, between two disjointed portrayals – each of these stories has a moment where Dex deliberately raises and drops the jovial act.

Life and Legend shows Obi-Wan and Dex at odds, meeting as potential foes. Dex plays up a cheery attitude in the face of unfamiliarity, setting the Padawan off balance in their first encounter. In The Last of the Jedi, Dex explicitly uses this act to trick another Jedi – Ferus Olin – into helping his people. He only drops it after Ferus catches on too late to turn back.

“I say we find it,” Dexter said. “Ferus has got the skills to protect us on the journey.”

Me? Ferus thought. Since when did I volunteer? …Wait a second, I thought I was getting a guide, not leading a group. He shot a look at Dexter. His eyes were twinkling… if you could say such a thing were possible for a Besalisk’s beady eyes.

Oh, well. He’d been outmaneuvered.

Then, in Wild Space, where Dex and Obi-Wan have reached a deep level of trust with each other, Dex once again performs the chuckling business owner. This time, it’s to deflect suspicion from the true reasons for Obi-Wan’s visit.

“Obi-Wan!” Dex shouted… “Hey, buddy! What are you doing down here? I thought you were too grand for the likes of us in CoCo Town!”

Bemused, Obi-Wan stared at him. “Too grand, Dex? I’m sorry, I don’t quite—”

“That’s right! Didn’t you know it? You’re famous now!” …Dex turned to his breakfast customers like a conductor to his orchestra. “Hey, everyone! Recognize this guy? You musta seen him on the HoloNet, his ugly face is everywhere! This is Jedi Master Obi-Wan Kenobi, the hero of Christophsis!…Come on, you mooches, a round of applause!”

…Obi-Wan bowed awkwardly.

Well this isn’t exactly the low-key welcome I was expecting.

And then he grunted, hard, as Dex crushed his ribs in an enthusiastic hug. “Play along,” his friend whispered. “You never know who’s watching.”

Once the two have retreated to privacy, the act vanishes. In its place, the serious, cantankerous information broker appears.

This dance between Dex’s external performance and his internal cunning is the same defining feature of Long John Silver in Treasure Island. But there is one other element that needs to be considered as we move into the new canon: Silver’s deception works because he plays specifically on class expectations.

On the Quality of Manners and the Size of Pocketbooks

“Silver is diffident to [the ship’s officers and financier]… He does everything he can to appear to be a humble ship’s cook…” [2]A. M. Davis, Handsome Heroes & Vile Villains: Masculinity in Disney’s Feature Animations, John Libbey Publishing, 2014.

Whether Robert Louis Stevenson was supportive or critical of the class structure of his time – academics have made both arguments [3]I. Nabaskues, “Law, Crime, Morals, and a Sense of Justice in Treasure Island,” Oñati Socio-Legal Series, vol. 8, no. 7, pp. 1001-1019, 2018. – Treasure Island functions as an exploration of the dichotomy between the wealthy gentry and impoverished lower class, with the poorer characters demonstrating foolish and boorish natures.

However, Long John Silver’s duality between deferential cook and dangerous pirate is meant to blur that line. The heroes discard warnings that clearly describe Silver – “the sea faring man with one leg” – because his act as a domestic cook undercuts what they expect from the vicious, lower-class pirates.

Even the clever magistrate, Dr. Livesey, is swayed into trusting Silver by his good manners [4]L. Honaker, “‘One Man to Rely On’: Long John Silver and the Shifting Character of Victorian Boys’ Fiction,” Journal of Narrative Theory, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 27-53, 2004.. Long John Silver “defies the stereotypical image of the pirate. He is clean, clever, cunning, and instead of being gullible, he is capable of deceiving the gentry.” [5]M. Hoorvash and S. Rezvanjoo, “Treasure Island and the Economy of Hegemonic Resistance,” Journal of Language Horizons, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 89-105, 2017.

Long John Silver deliberately plays into the wealthy’s class expectations, their assumption of their own inherent superiority in manners and intelligence, to set them off their guard. Silver’s friendly act hides the internal cunning beneath, allowing scrutiny to slide off of him until it’s almost too late.

A Goddamn Cook?

As we move now into the Disney-era canon, we see that not only has Dexter Jettster maintained Silver’s iconic duality, but additional emphasis is given toward class dynamics.

In the 2018 reference book Scum & Villainy: Case Files on the Galaxy’s Most Notorious by Pablo Hidalgo, Inspector Divo of Coruscant law enforcement takes Dexter Jettster’s friendly persona at face value. Around the time that the Clone Wars were beginning, he wrote:

“Dex is a good being. A checkered past, no doubt, but he’s made amends and is making a clean living. It’s no fault of his own that his open and welcoming nature attracts clientele of all stripes to his diner. Our investigations show no connection on his part to the deals cut at his tables. Though he wasn’t overly cooperative with us because he didn’t want his place tarred by a reputation for intruding into private affairs. I can respect that. We kept our distance, but we did keep an eye on the place.”

In a manner quite similar to Dr. Livesey accepting Silver’s humble cook persona, Divo’s assessment of Dex misses the fact that the wily cook has a hidden port to a smuggling tunnel in the back of his diner (Aftermath: Empire’s End) and used the black market for supplies as the war broke out (Queen’s Hope).

While Divo seems to remain blissfully unaware of the wool pulled over his eyes, Anakin Skywalker in Brotherhood found himself encountering the reality of Dexter Jettster with a shock.

“This can’t have any official traces. It needs an information broker.” [Obi-Wan said.]

… “Information broker?” Anakin asked, his voice quieter. “Is this what you do in your free time?”…

Obi-Wan responded without reaction. “We need to act quickly. Contact Dexter Jettster on Coruscant in the CoCo district. He will send you a secure channel to upload. Tell him it’s from me.”

“Wait, doesn’t he own the diner? How does that come into play?”

“Inheritance”, the Insider short story, sees Dex cheerily stalling for time by preparing a meal. Here, Dex falls once again into the expectations of a diner cook, lulling a violent mercenary into dropping his guard. In Padawan, Dex becomes Obi-Wan’s inside man against the antagonist: Dex’s own employer, towards whom we see Dex briefly apply a deferential act.

In fact, the very existence of Dexter Jettster in Obi-Wan’s life – from a metatextual level – was built as a challenge to the assumed class superiority of the Jedi. And Obi-Wan’s ability to see past those expectations is what makes him an effective knight.

“Later on we go back to the Jedi Temple to the library and get the sense of sort of arrogance on the part of the Jedi in terms of [how] they think they know everything, but in this case, this café owner knows more than what’s in the Jedi library.

I also like the fact that Obi-Wan’s got a lot of friends in the galaxy. He’s got a lot of contacts, a lot of unorthodox ways of doing things.”

– George Lucas, Attack of the Clones Audio Commentary from archival interviews with cast and crew

There is, of course, one critical difference between Dexter Jettster and Long John Silver that keeps Dex from simply being Silver with a new layer of paint. A difference that makes Dex his own distinct character.

While they both hide their cunning beneath jovial class expectations, their motivations could not be more different. Silver’s act vanishes when he has the upper hand or when his goals demand ruthlessness. Dex’s act vanishes when he has trust – as we have already explored – or when his compassion demands vulnerability.

So, My Friend, What Can I Do for You?

Across Legends and canon, Dexter Jettster consistently demonstrates compassion and an understanding of responsibility to the people around him. Unlike Long John Silver, whose ambitions do not extend past himself, Dex’s ambitions are consistently community-oriented. Also, unlike his deliberate dropping of the act when he trusts someone, Dex’s compassion consistently causes the act to unintentionally crack and leave the old Besalisk’s emotions vulnerable.

In Life and Legend, Dex breaks from his jocular persona not because Obi-Wan has earned his trust. Instead, Obi-Wan gets a glimpse of Dex’s true nature because the community around Dex is hurting, and the scoundrel’s compassion demanded that he “just had to do something.” In Wild Space, Dex’s cantankerous nature is provoked by the reality that there’s only so much he can do in the face of the war at large. And what he can help with – the intel that could save an entire planet from General Grievous’s slaughter – is bare-bones at best.

Obi-Wan stared. “Since when were you such a cynic?”

“War brings out my better nature,” said Dex. “…if you make this war [look] too neat and tidy, Obi-Wan, could be folks won’t mind how long it lasts.”

…Dex sighed. Suddenly he looked weary and years older. “I wish I could tell you more, Obi-Wan. But I can’t, so you’d best go.”

This compassionate vulnerability made an explicit leap to Disney canon in Wallace’s The Smuggler’s Guide. Here, in the most intimate look we get of Dexter Jettster, the act doesn’t just slip. It gets absolutely shredded to pieces as Dex finds himself in a position where he thinks he can’t help at all. A journal entry that had been exuding Dex’s usual boisterous confidence breaks, as he encounters a Crimson Dawn labor camp working its employees to death.

“I can’t save them all. I’m just one person. I can’t even save one of them.”

By the end of his entry in the Guide, Dex overcomes his doubts and puts his information-broker skills to work. He comes away rescuing one laborer and sending out intel that might help the rest he left behind.

Another early Dex reference in the new canon would be an indirect look, but with implications of community action on his part. In Aftermath: Empire’s End by Chuck Wendig, Dex’s Diner is described as derelict during the last days of the Imperial era. But even in that dereliction, the locals of Coruscant were able to use the hidden tunnel beneath the diner to strike a decisive blow against the Empire. No context is given for why the diner was abandoned, but the existence of the smuggling tunnel provided in the context of rebellion implies previous resistance efforts by the Besalisk.

In the 2022 releases, those implications of community action become explicit. In “Inheritance”, Dex’s goal in distracting the mercenary is to create an opening for his staff and patrons to escape. When he makes his move, Dex draws the attention, the ire, and the blaster fire of the mercenaries to himself.

In Padawan, our first encounter with Dex is the Besalisk confronting the book’s antagonist, Dex’s temporary employer, with “accusation in his tone and tears in his eyes” [6]While Dex is not explicitly identified as the speaker here, if we look at the way Kiersten White identifies or declines to identify characters within Padawan‘s limited-third-person perspective, … Continue reading as he hears his coworkers’ screams over the comms: “None of those crews signed on to die for you.”

Then, as he and Obi-Wan team up, Dex becomes a safe haven in their plans. He rallies and gathers the bystander miners and minors, taking responsibility for their safety so that Obi-Wan can focus on defeating the antagonist.

These were more hands-on efforts by Dex, but Brotherhood also sees him taking a wider perspective on the galaxy. While not placing the same wide-eyed trust in the Republic that Obi-Wan has – “Your idealism is adorable,” he laughs at the Jedi – Dex nevertheless holds strong opinions about the neutrality of systems like Cato Neimoidia and Mandalore.

While he holds no judgment toward the people, he believes that the Neimoidian government’s refusal to take a side makes for a breeding ground of violent extremism, something that is detrimental to the galactic community as a whole. He spends an entire night helping Obi-Wan craft a proposal to solve a crisis on Cato Neimoidia, a proposal that is then given to the most powerful people in the galaxy.

If Brotherhood depicted Dex helping Obi-Wan see communal responsibility across species on a galactic level, Queen’s Hope shows that Dex understands that this high level of politics can’t fix everything.

In this novel, Sabé feels lost in the pull between helping Padmé with galactic politics and helping free just a few souls on Tatooine. When she visits Dex’s Diner to get out of her own head, Dex uses a metaphor about food supply lines that encourages her to return to the hands-on community work of Tatooine: “One crate in the right place can change everything. Those up there [in the senate] don’t think about things that small.”

Within his compassion, Dex once again blurs the line separating different class expectations. While maneuvering his way to affect upper-class movements, he holds the efforts of the lower class with equal weight. He anonymously shapes senate-level proposals of galactic import, while putting his own hands to the small, messy work of helping the community around him.

Long John Silver states directly that his plan in securing wealth is to rise into the upper class himself, while being quite content to leave his crew behind in poverty or death. By contrast, Dexter Jettster has demonstrated through multiple stories that personal upward mobility means less than his responsibility to those around him. While similar in their tactics, Silver’s and Dex’s motives remain far apart.

Literature & Legends

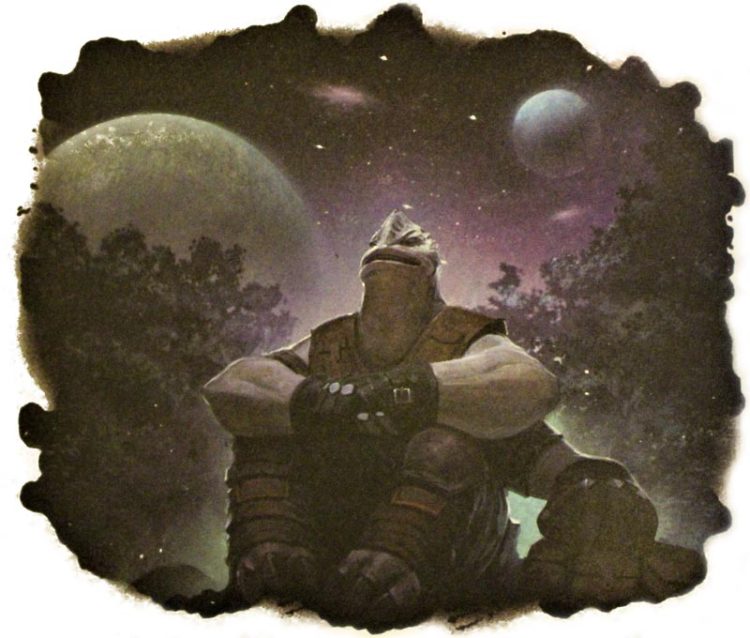

Dexter Jettster may never have been the product of a sole creator like Stevenson. But at this point in literary history, neither is Long John Silver.

Not only has the old sea dog been reinterpreted across a myriad of adaptations and retellings, twenty-first-century academics and readers are still returning to apply new lenses to Stevenson’s original works. English teachers look to him and his complexity as a way for students to apply critical thinking to their own interpretations [7]M. Mendelson, “Can Long John Silver Save the Humanities?,” Children’s Literature in Education , vol. 41, p. 340–354, 2010.. Star Wars itself has plucked aspects from Silver to flesh out its own characters. In many ways, Long John Silver has become a product of a collective.

While beloved by fans, Dexter Jettster may not have acquired the level of analysis afforded to the likes of Long John Silver or to the leads of Star Wars. Nevertheless, from 2002 to 2022, across two separate continuities, a collective of writers and artists – including many that I was unable to address here – have brought him into being. Consistent notes have been struck along the way, even in seemingly disparate portrayals. As a result, these twenty years have seen a character emerge as complex as classic literature’s most beloved scoundrel.

| ↑1 | Thank you to Meg Humphrey of Rogue Podron for sensitivity reading on the extended discussion of fatphobia at the link, a portion of which was reused here. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | A. M. Davis, Handsome Heroes & Vile Villains: Masculinity in Disney’s Feature Animations, John Libbey Publishing, 2014. |

| ↑3 | I. Nabaskues, “Law, Crime, Morals, and a Sense of Justice in Treasure Island,” Oñati Socio-Legal Series, vol. 8, no. 7, pp. 1001-1019, 2018. |

| ↑4 | L. Honaker, “‘One Man to Rely On’: Long John Silver and the Shifting Character of Victorian Boys’ Fiction,” Journal of Narrative Theory, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 27-53, 2004. |

| ↑5 | M. Hoorvash and S. Rezvanjoo, “Treasure Island and the Economy of Hegemonic Resistance,” Journal of Language Horizons, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 89-105, 2017. |

| ↑6 | While Dex is not explicitly identified as the speaker here, if we look at the way Kiersten White identifies or declines to identify characters within Padawan‘s limited-third-person perspective, we see a pattern. For the most obvious example, the antagonist is hired by a mysterious financier, only identified by a “deep voice.” This was the same cue that White used earlier for the reader to identify Dooku even when Obi-Wan is in the dark. Only two characters on the mining crew have any prominence in Obi-Wan’s story: Dex and the man who tried to kill Obi-Wan. In the sections written from the antagonist’s perspective, only two of the mining crew have any prominence: the representative of the financier (who tried to kill Obi-Wan) and the crew member who confronted him about the deaths of his coworkers. Therefore, following the pattern of identifiers and significance to the story between Obi-Wan and the antagonist’s perspectives, we can conclude that Dex was the sole crew member who spoke up for his dying coworkers. |

| ↑7 | M. Mendelson, “Can Long John Silver Save the Humanities?,” Children’s Literature in Education , vol. 41, p. 340–354, 2010. |