When Luke agrees to train Rey in The Last Jedi, the first thing he asks her to do is explain the Force. She says it’s the power to “control people and make things float.” It’s played as a joke, one the audience is expected to be in on. But really the joke’s on us. While we’ve all heard Obi-Wan and Yoda explain what the Force is countless times, the Star Wars fandom is constantly proving that we still don’t get it. Every time someone suggests Jar Jar’s Drunken Fist fighting competence proves he’s a Sith, or writes a story implying that the Force blew R5-D4’s motivator, we show we still think of the Force like Rey—just a box you have to check to unlock the skill tree of cool powers.

Part of the problem is that the explanations Jedi like to give aren’t actually very clear. Calling everybody “luminous beings” doesn’t shed much light on the question. There’s a simple answer, but it’s dressed up behind a veil of Orientalist mysticism that makes it hard to extract. I can’t say it ever occurred to me until I read Nick Lowe’s Well Tempered Plot Device. Fair warning: once learned, it can’t be unlearned.

The Force is the plot.

It’s that simple. Every single thing in the story, from the luck of a sabacc draw to the very fabric of the entire GFFA, is the Force. “Nothing happens by accident” because everything in the story is a conscious decision by the author.

There are two ways to look at what the nature of the Force means for Star Wars as a setting for good fiction. Lowe’s take is negative: the Force is an all-purpose deus ex machina that creates or solves any problem the author wants it to, relieving them of the burden of dramatically justifying everything. This is often a valid line of criticism. Lots of Star Wars stories have been bad and the Force has enabled their badness.

To your typical Star Wars fan—even those curmudgeonly fans who find more to complain about than to celebrate—this is nonsense. There is something special about Star Wars, and the Force is an inextricable part of it. The question is not whether the Force is a good thing or a bad thing for storytelling per se, but rather what opportunities and pitfalls does it create for telling good stories?

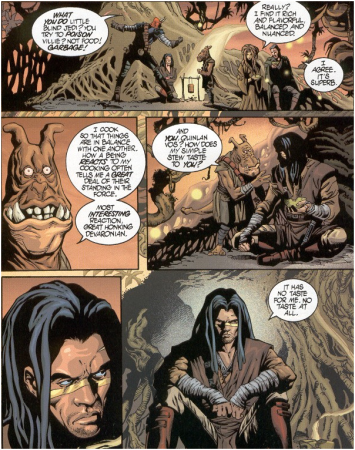

One opportunity is the “Force as Tao” angle, which Rogue One used beautifully (as Mike Cooper has explained). In short, it’s why Chirrut’s death-defying walk feels like walking on water, not plot armor. This is one of Star Wars’ classic tricks, and it can be one of the best tricks in its bag–from Qui-Gon’s attunement to the Living Force to Master Zao’s soup (arguably still the best use of the Force in the whole franchise). It’s no coincidence that inverting this trick is one of the biggest themes in The Last Jedi.

One opportunity is the “Force as Tao” angle, which Rogue One used beautifully (as Mike Cooper has explained). In short, it’s why Chirrut’s death-defying walk feels like walking on water, not plot armor. This is one of Star Wars’ classic tricks, and it can be one of the best tricks in its bag–from Qui-Gon’s attunement to the Living Force to Master Zao’s soup (arguably still the best use of the Force in the whole franchise). It’s no coincidence that inverting this trick is one of the biggest themes in The Last Jedi.

No one in The Last Jedi goes around invoking the Living Force, but almost everyone makes big gambles and relies on serendipity to fall in their favor. And, almost universally, they fail spectacularly. Like Luke, Poe takes a small squad of snub fighters to take out an enemy superweapon capable of destroying the Rebel base from orbit; almost everyone dies, but they complete the mission. Like Qui-Gon and Obi-Wan, Rose and Finn take a detour from the main plot to solve a logistical issue, expect to use a simple solution, find that it fails, and take the first option the Force presents them instead—no matter how suspect or implausible it is. Like Luke, Rey impulsively confronts a fallen Jedi before her training is complete, gambling her life on her hope in his redemption.

The difference is that this time the author refuses to reward that behavior. On a thematic level, this functions as a critique of toxic masculinity and protagonist arrogance. But metafictionally, it’s a cruel betrayal of the faith characters place in the Force, in the author. There’s a compelling argument that the light side can be defined as abandoning ego and accepting your role as a tool of the Force, that the dark side comes from imposing one’s own will on the universe (this is, after all, the whole point of Anakin’s prequel arc). The problem with that definition is that it only works when the author buys in and fulfills their part of the bargain.

More importantly, it requires a myopic view of the Force–exactly the view that Yoda, Qui-Gon, and most recently Luke are constantly warning against. It makes no sense to say that dark siders are acting against the will of the Force because the dark side is just as much a part of the Force, just as much an expression of the author’s will, as everything else in the story. In Knights of the Old Republic II, Kreia uses a trite parable to illustrate this point. The player has the option to give money to a beggar or threaten to kill him. Either option leads to violence. Kreia’s explanations are often mistaken for generalizable philosophical points—e.g., charity leads to dependence—but Kreia emphatically puts the blame where it belongs: “The Force binds all things.” The choices you make don’t matter not because nothing matters, or because it’s impossible to improve the world, but because there is an all-powerful observer shaping the outcomes of your actions in ways you can’t anticipate or outsmart.

The Last Jedi teaches this lesson with a much more serious problem. Luke finds himself teaching a Jedi of unprecedented power and unfathomed capacity for evil. He knows how the story ends if he ignores it and hopes for the best. So he tries the opposite approach. And gets the same result. The Plot needs a Vader, so one appears. All choices are bent to the necessary outcome.

Which is to say, the Force is identical to the story, but it isn’t just a neutral box that holds whatever the author decides to do. It has a template, a value system, a set of archetypal roles to be filled. By the time of The Last Jedi, both Luke and Snoke intuit parts of this structure. Snoke knew that as Kylo Ren grew strong in the dark side, it was inevitable a hero would rise to match him. Snoke invokes a small-b balance, adjusting the sides to make the fight interesting. It matches the intuitive understanding of the Balance of the Force as light = dark, but Luke’s insights prove that intuition is still as wrong as it’s always been.

Balance is central to Luke’s explanation of the Force, but he never explains what it is. It’s as mysterious and confusing as it’s been since The Phantom Menace. This is another place where the Force-as-Plot framework can cut a knot that can’t be untied. Reconsider what Luke said about balance: “For many years [between Episodes VI and VII] there was balance.” Among the lives and deaths and peace and struggles of Ahch-To as well: balance. What unites these things? It isn’t rule by a representative democracy, or some kind of static ecological harmony. It’s the absence of narrative tension. Anakin brings Balance to the Force by ending the story. There is balance between the creatures of Ahch-To because the story doesn’t care about them.

This is the dirty secret of the Force. It wants us to believe it’s on the side of light because the light always wins. The truth is that the Force hates balance, because the Force is the Plot and the Plot demands violent conflicts between good and evil that endanger and kill billions of people. For anyone living in the Galaxy Far, Far Away, the Force is a pretty scary thing. Despite the spiritual value it holds for some, the beings in the galaxy would probably be better off without it.

By the time of The Last Jedi, Luke has come to understand this. Having been around the block for one trilogy, he intuits the cycle of violence underlying the Sith and Jedi conflict. And though he knows it isn’t ideal, for much of the movie he believes it’s better to end the war by letting the Sith win than to perpetuate the cycle. “The Jedi must end” because if there are no Jedi, they’ll have to stop telling stories about Jedi. What matters is Balance: i.e., getting the Author to stop making people kill each other.

In more ways than one, Luke echoes Kreia. Both of them failed to prevent their pupil from becoming a dark lord (their students even dressed the same). And both sought to end the cycle of violence by removing the influence of the Force. Luke’s plan was characteristically impulsive and nonviolent; Kreia’s was scheming and apocalyptic.

They’re both doomed to fail, but the difference is one of tone and character. Kreia’s rhetoric is unremittingly negative–as her creator, Chris Avellone, put it, “Kreia is my mouthpiece for everything I hated about the Force.” KOTOR II failed in part because it put all its emphasis on killing the Force but found no way around the fact that killing the Plot is impossible. In The Last Jedi, Rian Johnson managed to be critical without burning bridges (or writing himself into a corner). Luke has to confront the futility of his position, forcing him to look for a way to be a Jedi that feels true to what he has learned about the Force.

The Force is unique in all of fiction as an embodiment of the author that the characters interact with. It’s a powerful (and dangerous) tool for writers, all the more so for its familiar and unpretentious history. The Last Jedi uses a self-aware lens on the Force to find new and compelling stories to tell. In doing so, it proves that this approach is invaluable in moving Star Wars forward without compromising its identity. But it only scratches the surface of the possibilities it offers.

There’s a lot to consider here. A few thoughts:

1) How do we understand the relationship of the Force to the autonomy of the characters within the narrative? While I enjoy the idea of the Force as authorial will, I think that arguing that the Force is the totality of everything within the narrative ends up conflating the Force with “the author” himself. Obi-Wan tells us in Episode IV that the Force guides a Jedi’s actions, but it also obeys his commands. This suggests that at least within the narrative characters have “free will” beyond the dictates of the Force. Thus, while everything within the narrative is the result of the *author,* contra Kreia not everything within the narrative is necessarily the result of *the Force.* I think a valid argument can be made, therefore, that the Sith *are* a perversion of the Force, driven by the individual will to dominate. The fact that the Sith are a creation of the author does not necessarily entail that they are a creation of the Force.

2) If the Force is not necessarily synonymous with the author, then I also wonder whether we need to consider authorial intent in addition to the text of the work itself. Back in the pre-Disney days, George Lucas used to argue (again contra Kreia) that “balance” in the Force was not somehow a balance of light and dark – that the pursuit of the Dark Side (fear, hate, and aggression) was the cause of imbalance, while the properly balanced Force represents life, compassion, and selflessness. This distinction is not always clear in the text itself – as you note, “balance” is a nebulous concept in Star Wars – but if the Force is an extension of the author within the plot, then I think we could argue that drawing on authorial sources beyond the text makes sense.

3) This is more a response to Lowe than the above, but I wonder whether the deployment of plot devices are quite so regressive. As Lowe himself notes, The Ring in the Lord of the Rings serves not just as a plot device, but also as an opportunity for pretty significant commentary – on modernity, technology, temptation, and trauma. Similarly, I would argue that the way that the Force is employed serves to advance themes that go beyond its role as a plot device, especially the central dilemma regarding violence and virtue – if balance in the Force represents compassion and selflessness, then isn’t standing up to imbalance in and of itself an imbalance? How do we fight our enemies without becoming our enemies? In this regard, I don’t see The Last Jedi as being particularly darker or more challenging than previous works – instead, it carries forward a theme that has been embedded in the Force from the beginning.

Again, many thanks for an interesting read!

1) I watched ANH after finishing this piece and that Obi-Wan quote stood out to me. So in theory I do think it’s correct to conflate the Force and the author, 1:1. But it’s more like the Force is a mask the author wears, a kind of shell game. The Jedi, like real people, perceive themselves as having free will because they only partly grasp the net of causality that determines their lives. They take their ability to control the Force for granted, but we know the author can take it away at any time.

2) Yes, 100%. Of course you can bring all that material to the table regardless, but this framework does help clarify things. I wonder sometimes about what it’s like to do moral philosophy or just psychology in a universe where one man’s hypotheses are enforced by the universe itself. “Pathological fear of loss can lead to socially harmful behavior” is a much different thing than “fear of loss makes you vulnerable to demonic possession.” The Pop Culture Detective video on the Jedi is really great on this point: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tUPD1w78D5I

3) I agree, although I think this is one of the treacherous areas for authors trying to take advantage of the Force. The Broom Boy sublot in TLJ shows how corny and uncomfortable it can get when the author uses the Force to speak the themes directly to the audience.

Again, although I like the idea of the Force as the author’s mask, I’d also maintain that all of the characters are also authorial masks, and that the author might use different masks to make different points. If everything (and not just the Force) is ultimately an expression of the author, then there might be things (like the Sith) that are necessarily an authorial invention, but *not* an expression of the Force, properly understood. This would also allow us to reject the Avellone/Kreia claim that the Force is somehow directly responsible for every bad thing that happens in Star Wars. The author demands conflict in order to advance the plot, but that is not the same thing as saying that the Force demands conflict, because the Force is only one of the authors many masks driving the narrative.