For those who might be unfamiliar with the term, a “grandfather clause” is, broadly speaking,

law : a part of a law which says that the law does not apply to certain people and things because of conditions that existed before the law was passed

Put simply, in this context, it’s when a particular work of fiction can get away with something primarily due to when it was made, while that exact same thing would not be nearly as welcomed by audiences in a more modern product: something with which I think most Star Wars fans are familiar.

That we can blindly accept psychic monks knocking laser bolts out of the air with the blades of their laser swords and still utter the title “Grand Moff” with a straight face are truly testaments to the Original Trilogy’s enduring ability to convince us to take even its most absurd core elements seriously. There is also a certain historically significant implementation of the principle which is worth noting, but otherwise of no relation to what we will be discussing today.

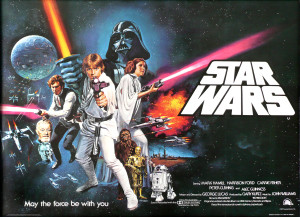

When the saga’s first entry was released in 1977, it was quite unlike any one thing that had come before (or after, for that matter), though at the same time it was also quite like many things that had come before. Its sources of inspiration transcended mere boundaries of time and space and genre, being a bizarre mashup of feudal Japan, Buck Rogers and the 21st Century, Frank Herbert’s Dune, and World War II, among countless other esoteric ingredients.

Somehow, it managed to capture the public imagination, and the rest is, as they say, history. With the release of Episode VII coming up next year (or possibly the year after), close to four decades will have passed since the first installment in the series: a degree of enduring success encompassing time, number of entries, and profits that is rivaled by only a handful of franchises, Star Trek and James Bond prominent names among them.

Like Bond’s larger-than-life villains and improbable gadgetry or Star Trek’s blatant disregard for scientific plausibility and non-humanoid alien species, Star Wars comes with its own set of unique and iconic characteristics that have accumulated over the course of the saga. Laws of physics that bend according to what the audience will find most visually impressive, an eclectic technological mix of the antiquated and the futuristic, and stories that owe more to fantasy than they do the setting’s superficial layer of science fiction, among other things.

Compared to other, similar franchises, Star Wars is perhaps the most unusual in its melting pot approach: few other works have ever successfully drawn together so many disparate elements and codified them into a universe second only to our own in terms of size and population. This is where the grandfather clause comes in. We would (rightfully) not hesitate to excoriate any modern work that attempted such an absurd combination, but we are more than willing to permit and even celebrate that same feat when embodied in the form of Star Wars. Its seniority as a distinguished elder franchise has earned it special exemption from the changes that audience expectations have undergone with the passage of time.

But let’s put all that aside for a moment, as we’re drifting away from the true thrust of the topic. Even measured against its chief rivals, Star Wars’ monopoly covers an unusually broad territory. Bond films are, after all, the very embodiment of the word “formulaic.” Star Trek is normally expected to involve trekking through the stars in at least some capacity: see the backlash against the recent Abrams films as a prime example of what happens when a franchise violates its own established boundaries. Star Wars, however, is the product of a truly remarkable combination of genres and has already established itself as a story far from reliant on a single character or even group of characters.

It’s a heroic journey, but also a war story pitting insurrection against empire, a tale of cosmic conflict between light and darkness, but with a touch of romance and a hint of swashbuckling flavor, occasionally dips into political thriller territory, has more than a few elements of a western, with a visual layer of science fiction on top, and that’s just where we started. It would be shorter to list what we haven’t tried to incorporate at one point or another.

Unlike its more constrained brethren, Star Wars has essentially crafted for itself a blank slate to play with. Audience expectations are fairly limited: we’ve covered so much varied terrain already that few would blink twice if we were to attempt something new. The core concept is just that flexible: it’s a universe that can accommodate almost any kind of story that also conveniently serves as the backdrop to a saga that gleefully embraces that freedom. There are few, if any, stories that can’t be fit in somewhere.

If we can do zombies, we can do anything. What we have in our hands is a tale that not only theoretically permits a “kitchen sink” approach to such things, but also wholeheartedly endorses and practices it with wild abandon. Most filmmakers and writers can only ever dream of such liberty accompanied by audience loyalty such as ours: to know that no matter what you choose to do, there will be hordes of devoted fans clamoring for the opportunity to pay for it.

So, let’s ask ourselves, what ought we to do with this incredible privilege we’ve been afforded? Certainly, we can do what we’ve largely done so far, and milk the existing set of characters and plots for every single dollar they’re worth. But that seems more than a little wasteful, and I think we can do better than that. Nobody else, with the possible exception of Marvel (which is now under the same umbrella as us, anyways), is in a position as strong as we are.

No new author or filmmaker will be able to come close to what we’ve obtained for decades to come: the announcement of the Sequel Trilogy has made sure of that. We have no obligation to follow in anyone else’s footsteps: should we choose to exercise our power, we have the influence to make others follow in ours. We have one of the most flexible fictional universes in existence, one that can accommodate virtually any kind of story we wish to tell, and an audience that is, at the very worst, tolerant of attempts to step outside our usual comfort zone, and often actively welcoming.

It must be acknowledged that Star Wars is, at heart, a product. It owes its lengthy existence to the consumers that continue to purchase the works it churns out. If its owners did not believe there to be a viable market for the Sequel Trilogy, there would not be a Sequel Trilogy in the works. To expect it to behave without regard for popular demand or financial success would be absurd, but at the same time, I do believe that there is room for considerable experimentation without wholly abandoning our adherence to the principles of capitalism.

Unlike many other works, particularly those that are the first installments in their franchises, our position is not a particularly precarious one: something dead on arrival here or there will not bring the whole house of cards crashing down on our heads. That much, we know from experience, several times over. We also know from the experience of others that a franchise that encompasses a wide variety of themes and protagonists is a viable one: see the influence of the undeniably profitable Marvel Cinematic Universe on our own plans for the Sequel Trilogy and assorted spinoffs going forward.

What remains, then, is to invest in the opportunity to exploit the vast untapped potential still left in the franchise. If we wish for Star Wars to be known for more than merely reliving its successes of decades past, then there is no time better than now to do something about it. We have the audience. We have the publicity. We have the tools. I suggest that we use them.