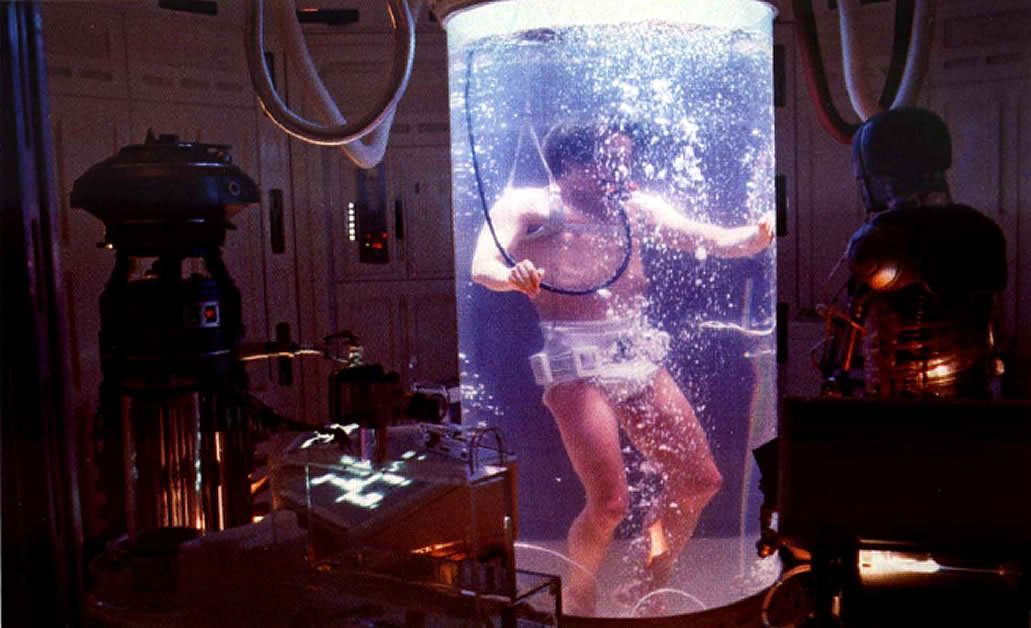

From a few brief scenes with a diapered Luke Skywalker floating in a tank of clear (later established to be blue) liquid came one of the franchise’s most enduring futuristic inventions: that mysterious, miraculous live-saving fluid we call bacta. In go the wounded, out come the hale and hearty. A universal cure for anything and everything that ails you. Incredibly convenient, without question, but also a rare instance in which we’re permitted a glimpse of a technology that is most decidedly not a straightforward science fiction counterpart to something from our own world.

At least not yet, anyways. There are obvious questions that come to mind: where does it come from? How does it work? Who controls the supply? All valid questions at the moment, as their established answers have been washed away in the all-consuming deluge that is the big red button labeled “reboot.” So let’s ask a different question, instead. We’ve seen what bacta is capable of, so what else might they be able to do that we can’t?

We’ve discussed a similar subject before. The galaxy far, far away can quite easily provide mechanical substitutes for lost limbs and severed appendages, but what about options of a somewhat more organic nature? Prosthetics continue to advance in sophistication, but they’re far from our sole focus, and efforts continue to be made to discover alternative means of recovering what has been lost. Some have even gone so far as to propose that one day we might find a way to regrow our extremities, as some lizards have been known to do after having their tails cut off.

Others have studied ways in which we might clone organs for transplant, circumventing the issue of rejection and the need for a suitable donor entirely. Given the apparent attitudes toward cloning in Star Wars, one wonders whether or not such science would be considered permissible. If not, is there a black market for organ cloners? Do we have a Larry Niven-esque situation on our hands in which the smuggling of organs constitutes a lucrative underground trade? Perhaps spice is not the only illicit cargo that Han Solo has transported in his time.

Something frequently noted in the final years of the departed Expanded Universe was the continued focus on the same beloved heroes that we’d been reading about for decades despite their increasingly advanced ages. Virtually never discussed or referenced in any of these works were potential reasons for their enduring spryness. The subject of immortality has, for obvious reasons, long been one of considerable fascination for the human imagination: a dream that many have hoped would one day become reality, whether it be in the form of a mythical Fountain of Youth or modern corporate mammoth Google’s recent investments into longevity and rejuvenation research. Within the context of Star Wars, such possibilities are far more than merely theoretical, the 1994 novel The Truce at Bakura having established that the natives of that world enjoyed lengthy lifespans well above the human norm (one Bakuran character’s age was set at 132, and another at 164).

A minor background character in Revenge of the Sith known as Duke Teta was said to have lived three centuries and looked like he might have lived a little over half of one. Near the end of the original Expanded Universe, James Luceno’s Darth Plagueis made mention of several methods by which a life might be prolonged in the titular character’s quest for true immortality. Now, I would certainly never be one to advocate keeping Luke, Han, and Leia in the spotlight any longer than absolutely necessary, but such technology doesn’t need to be universal or convenient in order to get an interesting story out of it.

Now, we’ve taken a look at the ways in which the denizens of the Star Wars galaxy might stave off death’s inevitable embrace, but what about ways in which they could fundamentally redefine human (or alien) existence? We know that, from a variety of instances scattered throughout the Expanded Universe, they have already achieved a level of genetic engineering that far exceeds our own capabilities. The use of such technology to produce lifeforms with advantageous new traits has long been a staple of the science fiction genre, and in this we differ only in that we have not explored the possibilities it offers as thoroughly as others.

“Above all else, humans are adaptable — adaptable in terms of physiology, mentality and society. Their genome is remarkably elastic: Selection pressures need a few millennia at most to engage new genes and reshape their bodies in response to environmental changes, as the galaxy’s countless near-human populations attest.”

―Hali Ke, Kaminoan senior research geneticist

Alien species that are broadly similar in form to humanity but differ in small (but significant) ways have long been categorized as “near-human” offshoots that branched off millennia ago, overlooking the possibility that they might, in fact, be human. After all, why wait thousands of years for natural selection to do what can easily be achieved through science in the space of a single generation? In a galaxy where speciesism is hardly an uncommon attitude, blurring the lines between human and alien offers abundant opportunities to challenge preconceived notions, both in- and out-of-universe.

When we first met Han Solo, his profession was that of a narcotics smuggler. His cargo of choice: spice. A futuristic drug for a futuristic universe. Its properties, however, are rather more impressive than any similar proscribed substances from our own world, in some forms apparently being able to induce a limited form of telepathy in its users. Accordingly, there also exists an array of other stimulants that confer formidable advantages upon their users.

Powerful combat stims and adrenals can sharpen the mind, quicken reflexes, and boost physical strength well above human norms. It’s one thing to go up against a legion of some petty crime lord’s hired thugs; it’s another thing entirely when they all hit like Wookiees and are numb to pain. Even an otherwise completely average human being could pose a significant threat with a sufficiently potent concoction working its toxic magic on their body. In the worst case scenario, imagine some warlord running his own sector empire with an entire professional army with primed autoinjectors just waiting for the shooting to start at his disposal.

In a galaxy overflowing with alien species, worlds, and environments, it’s not unexpected that there exist just as many deadly alien plagues, diseases, and rots. For a franchise that loves nothing more than a threat that put billions or trillions of lives at risk, where traveling between planets is as easy and commonplace as booking a flight between countries, a virus is truly the ultimate insidious menace. In the New Jedi Order series, a pathogen by the name of Alpha Red was tailored to specifically target and annihilate the Yuuzhan Vong invaders (similarly, Ysanne Isard’s Krytos virus rather cleverly targeted only aliens, leaving humans unscathed), while the Confederacy unleashed the deadly Loedorvian Brain Plague on the Weemell sector during the Clone Wars, eradicating that region’s entire human population.

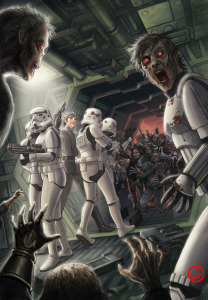

Though somewhat less of a concern in our own reality, the novels Death Troopers and Red Harvest dealt with your stereotypical zombie virus: while primarily examining it as filtered through the lens of the horror genre, it might be equally compelling to see such a plot handled from a more clinical (or even military) standpoint. While most plots dealing with biological warfare have thus far dealt with either preventing its use or seeing the devastation left in its aftermath, containment, treatment, and the desperate hunt for a cure all present as equally viable options. Certainly, such plots are sufficiently abundant in terrestrial fiction as to leave little doubt as to the demand for them.

For me, there is no absolutely no question whether medical science and technology can form a viable basis for a science fiction story or saga: doubters need only look to Star Wars’ own MedStar duology or James White’s Sector General series, and that’s not even beginning to scratch the incalculable number of novels and films dealing with everything from ancient doomsday viruses to pandemics engineered for profit to military-experiment-gone-wrong zombie apocalypses.

Some of which we have, in fact, tried ourselves on one occasion or another. Whether or not these technologies and fields of science prove themselves to be viable in our own future is ultimately irrelevant (a work of hard science fiction, we are not): what matters most is that they’re possible in the context of Star Wars, and that they might serve as solid foundations upon which to construct interesting new tales. All the necessary ingredients already exist: all that we need to do now is make use of them.