A fun game I’ve played once or twice since the release of The Force Awakens is to try and pinpoint a moment in time where you could tip the post-Endor timeline, Back to the Future-style, from the Expanded Universe’s version to the sequel trilogy’s version. As I recall, the best  idea I could come up with was Leia getting pregnant with Ben immediately—like, “the night of the Endor celebration” immediately. The impending child not only accelerates her coming to terms with her heritage (and motivates her and Han to marry sooner) but gives her a huge extra reason to end the war with the Empire as soon as possible. Sure enough, Leia taking an even more aggressive role in the military campaign brings about a swifter military victory, and perhaps even further motivates complacent core worlders to rally behind her as a post-Empire figurehead. This has all sorts of random ripple effects, too—different people come to lead the Imperial Remnant, Luke perhaps founds his new Jedi Temple sooner, and so on.

idea I could come up with was Leia getting pregnant with Ben immediately—like, “the night of the Endor celebration” immediately. The impending child not only accelerates her coming to terms with her heritage (and motivates her and Han to marry sooner) but gives her a huge extra reason to end the war with the Empire as soon as possible. Sure enough, Leia taking an even more aggressive role in the military campaign brings about a swifter military victory, and perhaps even further motivates complacent core worlders to rally behind her as a post-Empire figurehead. This has all sorts of random ripple effects, too—different people come to lead the Imperial Remnant, Luke perhaps founds his new Jedi Temple sooner, and so on.

Of course, while a fun thought experiment, this is complete nonsense. The truth of the matter is that the sum total of the “Legends-verse”, as many are inclined to think of it, is under no circumstances a single coherent timeline that could be switched on or off like a light bulb. Lucasfilm’s efforts to keep it consistent over the years were herculean and admirable, but I’ve come to believe that a more accurate way of looking at Legends is as a plethora of “pocket universes”, which fit together more nominally than absolutely.

An early example of this is the original Marvel comics. Due to constraints imposed by Lucasfilm at the time, their foray into the post-Return of the Jedi period had very little to do with the Empire and instead focused on an incursion by two brand-new alien species from outside the galaxy. While bearing little resemblance to the latter-day EU storytelling (okay, maybe a bit), this was actually one of the more interesting and creative runs of the series, at least until it was abruptly cancelled by LFL and a slapdash final issue struggled mightily to wrap up the various storylines. When the “modern” EU kicked off with Heir to the Empire and Dark Empire several years later, all hundred-plus Marvel issues were totally ignored—and they pretty much stayed that way for more than a decade. The thing is, nothing those comics did was really contradicted by the new material, it was more than nobody cared to utilize it. Consistent? Mostly. Complementary? Much less so.

What followed was in many people’s view the EU’s golden age—a steady stream of fairly decent (but very consistent) storytelling running from Endor until the official end of the war with the Empire fifteen years later. The Bantam era of storytelling could be seen as a pocket universe in its totality, but really, this period was marked by several different story arcs that featured many of the same characters but rarely overlapped in any meaningful way. If you liked military sci-fi Timothy Zahn and Michael Stackpole were your guys, and as the years went on (in and out of universe) they began exchanging characters and  plot threads in a way that may be entirely unique in the Star Wars franchise. If you liked your Star Wars more whimsical and fantastic, you had Kevin J. Anderson and Barbara Hambly for that. Bourne-esque espionage thrillers? Michael P. Kube-McDowell’s Black Fleet Crisis trilogy was a great story (in my opinion) that featured a huge original cast (plus Lobot), bore almost no resemblance to the stories surrounding it on the timeline, and included a great little Indiana Jones-style Lando adventure that itself had almost no relationship with the rest of the story those very books were telling.

plot threads in a way that may be entirely unique in the Star Wars franchise. If you liked your Star Wars more whimsical and fantastic, you had Kevin J. Anderson and Barbara Hambly for that. Bourne-esque espionage thrillers? Michael P. Kube-McDowell’s Black Fleet Crisis trilogy was a great story (in my opinion) that featured a huge original cast (plus Lobot), bore almost no resemblance to the stories surrounding it on the timeline, and included a great little Indiana Jones-style Lando adventure that itself had almost no relationship with the rest of the story those very books were telling.

The Bantam era is one of circles inside of circles, and something for everyone. Which is great when you consider the wealth of different stories the Star Wars universe is equipped to tell—the New Jedi Order and beyond have their good and bad qualities, but the fact is if they weren’t your cup of tea you were basically out of luck. From 1999’s Vector Prime all the way up to the twilight of the EU and Crucible, the post-Bantam EU was one ongoing narrative, and while I was hugely invested in that narrative at the outset and still look back on the NJO fondly, it’s easy to find people who tuned out of the EU around that time, and the longer it went on, the more people were alienated by the nonstop travails of the Big Three and their ever-dwindling supply of offspring. What it was, though, was interconnected in a way that Bantam had never even tried. Many would argue that consistency was a problem even within each series as different authors chose to highlight or abandon different characters and threads, but they were each still telling basically the same story.

Meanwhile, if you wanted EU storytelling that had nothing to do with what the Big Three were up to, there was one place you could turn—the prequel era. As the films were coming out and the books and comics rushed to expand upon them and fill in the cracks, we got another pocket universe that was much closer to Bantam’s. Political thriller? Cloak of Deception. Fantasy adventure? Rogue Planet. Even Zahn eventually got into the prequel game with Outbound Flight. But the real prequel pocket universe was a mixture of Bantam-style and NJO-style storytelling: the three-year, largely real-time Clone Wars multimedia project. Telling a variety of stories in novels, comics, and animation, covering everything from “Apocalypse Now in space” to “M*A*S*H in space”, the Clone Wars that unfolded in the EU from 2002 to 2005 were perhaps the high-water mark for balancing consistency and variety. A concrete timeline was established and held fast to across all forms of media, while at the same time the enormous palette of the war allowed for different creators to work to their strengths without having to worry about clashing with each other. Even when different media depicted the same exact events, as in the novel Labyrinth of Evil and the second season of the Clone Wars microseries, the creators had the sense to cater each version of the story to the format’s strengths at the expense of slavish alignment. Which version of Palpatine’s kidnapping was the “true” one? Whichever one you liked more.

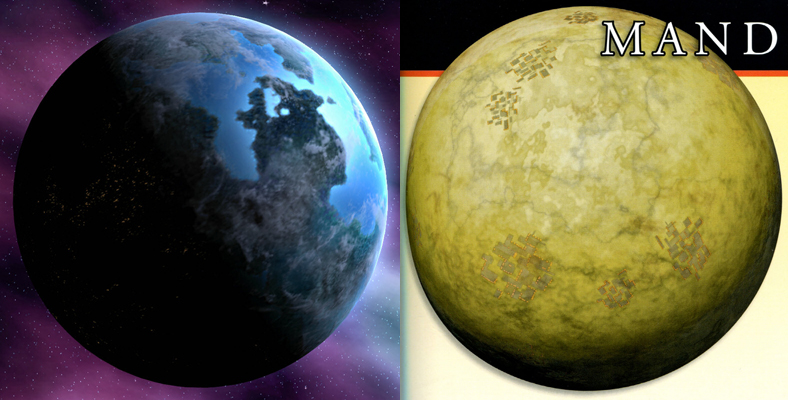

And for a while, it was good. Then The Clone Wars happened. While an official reboot was still a long way off, TCW demonstrated plainly and on a regular basis what many of us had always understood deep down: George Lucas was gonna do what George Lucas wanted, and if the EU clashed with those plans, it was their problem, not his. Suddenly, we had a planet Ryloth that was both tidally locked…and not. A Mandalore that was covered in desert cubes instead of woodlands. An Even Piell who was literally dumped into lava yet was still alive years later. And of course, five years’ worth of Anakin (with and without a spunky apprentice in tow) to fit into a three-year span of time.

The EU kept chugging along for another six years in this sort of quantum state—both consistent and a mess at the same time. Naturally reference books like the Essential Guide to Warfare began incorporating elements from TCW at the expense of the earlier material, papering over the minor inconsistencies and more or less ignoring the big ones. Even the far-flung Big Three were affected, as the mythology of the Mortis arc worked its way into the end of the Fate of the Jedi series. And then, at long last, came the reboot. Going forward, the inconsistencies no longer mattered; much of the worldbuilding of the EU remained intact, but where Lucas had gone a different way, his vision remained true.

But what of the “Legends-verse”? Did Anakin have an apprentice, or not? There are Legends sources that state both. Which Mandalore is the “real” one? They both are. If they had gone ahead and rebooted as soon as The Clone Wars started, it might have been harder to hang this argument on the EU’s lack of internal consistency, but things being as they are, I see no benefit in imagining an alternate timeline where the EU Clone Wars kind of happened, but TCW kind of did too. Or where Ryloth was tidally locked in ancient times, then not during the Clone Wars, then was again after Endor. And so on. I loved the original Clone Wars, and I loved those old Ryloth stories, but I think they’re more valuable when viewed on their own terms, not hobbled by efforts to bring them into line with later material they had no way to account for. The EU was never all that consistent, but the great thing about the reboot is that we no longer need to pretend it was. They’re all just stories now. Legends, even.