Politics have been part of Star Wars since the opening pages of Alan Dean Foster’s novelization of A New Hope told the story of how the Old Republic became the Empire not through a military coup, but because it rotted from within due to corruption. With the publication of Claudia Gray’s political drama Bloodline, and the revelation that its central conflict arose from suggestions by Episode VIII director Rian Johnson, politics are once again at the forefront of the Star Wars universe. But does the saga have a core political philosophy, or make a political statement? If it does, how does it relate to the overall philosophy of Star Wars? And can we use it to predict where the franchise might take us next?

Harmony and corruption in the old Republic

The Phantom Menace is the clearest statement of George Lucas’s political outlook, and we can use it as a starting point to follow this thread through the rest of his six-episode saga. On a narrative level, TPM is the story of Padmé Amidala, told mainly through the eyes of Qui-Gon Jinn: the core conflict against the Trade Federation is Padmé’s, and it is her choices – first to leave Naboo and appeal to the Senate, then to return and unite her people with the Gungans – that drive the story and give it shape. It is unlike any other film in the saga – not the mythic hero’s journey of a Jedi-to-be, but the story of a young woman’s political coming-of-age.

Padmé leaves Naboo because she believes in the ability of the Senate to save her people from the Federation. Arriving on Tatooine, however, Padmé is shocked to discover that there is still slavery in the galaxy, and that there are places where the laws of the Republic simply do not exist. Even Republic money is worthless out here, and the entire planet is controlled by gangsters. The implication is clear: the Republic doesn’t care about what happens on the galactic frontier. When we reach Coruscant, we discover that the Trade Federation, a corporation driven by profit, has its own seat in the Senate, giving it a voice in galactic affairs that is equal to any Republic system, and stronger than worlds such as Tatooine. Taking advantage of legalism and bureaucracy, the Federation is able to stall the Senate’s actions.

The Republic, says Padmé, “no longer functions.” The implication is that it once did, and Palpatine confirms this when he says “the Republic is not what it once was.” As we will learn in Attack of the Clones, this government has maintained galactic peace for one thousand years, but something has gone wrong. “There is,” Palpatine says, “no interest in the common good.” Palpatine is secretly the Sith Lord Darth Sidious and has engineered the Naboo crisis. However, he is as much an opportunist as he is a master manipulator, as he takes advantage of the corruption already festering in the Republic.

To resolve the crisis on her homeworld, Padmé has to act outside the Republic system, and the key to her victory is that she heals the rift between her people and the Gungans. Our two leads – Qui-Gon and Padmé – show compassion and empathy for Jar Jar Binks (unlike others, including Obi-Wan Kenobi, who finds Jar Jar irritating and refers to him – perhaps not entirely jokingly – as a “pathetic life-form”). Qui-Gon saves Jar Jar from punishment in Otoh Gunga, while on their first meeting, Padmé shows no sense of superiority over the Gungan; instead, she is kind to him, and interested in what he has to say. With Jar Jar’s help, Padmé humbles herself before the Gungans, as the two societies put aside their differences and work together for the benefit of both.

This is the core theme at the centre of TPM – symbiosis, and the need for life-forms to live in harmony for the benefit of all. As Anakin, quoting his mother, says, “the biggest problem in this universe is nobody helps each other.” The corrupt, self-interested system of the Republic is no longer able to achieve this harmony in galactic society. Padmé shows us how politics should be done – through empathy and co-operation.

This fundamental conflict between compassion and self-interest should be familiar to us: it echoes the key philosophical difference between the light side and dark side of the Force. However, though we are told that the Jedi are “guardians of peace and justice in the galaxy”, we quickly learn that it is not within the remit of the Order to free slaves outside the Republic. Anakin’s perception of the role of the Jedi is mistaken. It is a subtle point here, but we cannot escape the conclusion that by allying themselves so closely with the Republic, and taking their orders from politicians, the Jedi will be dragged down with them.

Separatism and the Clone Wars

Ten years later, in AotC, Padmé and Jar Jar, our two symbols of political unity, represent Naboo in the Senate. Padmé still believes that the Republic can be saved, and has devoted her life to it, but as thousands of systems secede from the Republic, war seems inevitable. This division is the very antithesis of the harmony that Lucas values. Padmé’s attempts to avert war through negotiation are all for naught, and in a tragic twist, it is Jar Jar – catalyst for the union between the Naboo and the Gungans – who is manipulated into proposing emergency powers for Chancellor Palpatine, and ushering in the Clone Wars. The naïve and innocent Jar Jar, the symbol of the harmony between peoples in TPM, is now a victim of a political system beyond repair.

The Separatist movement is orchestrated by the Sith, but from everything we see in TPM, its systems to have a genuine grievance against the Republic. It is unfortunate that the films only show us the financial and military elements of the Confederacy of Independent Systems, but in the Clone Wars TV series – particularly the episode “Heroes on Both Sides” – Lucas explores the political and civilian sides. The Separatists have their own parliament, and are rightly furious at the corruption in the Republic. Once again, Darth Sidious and his apprentice are opportunists, who nurtured a situation brought about by individual greed and self-interest. However, the Separatists are reliant on the Trade Federation to fund their war, and shadowy financiers have ultimate control over the government. For all the idealism of its people, the Confederacy is in practice no less corrupt than the Republic.

Throughout The Clone Wars, Padmé challenges corruption and militarism, and tries to forge a path of empathy and negotiation – as she states in Revenge of the Sith, “this war represents a failure to listen.” But at every turn, she is thwarted by self-interested parties that are too powerful for her and her limited number of allies to overcome. The story of Padmé Amidala is no Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. And we must again question the allegiance of the Jedi Order. When the Separatist movement rises, the Jedi become a wing of the Republic military, compromising their entire ethos, and while we see them question this role, they do not openly challenge it. The Jedi have drifted from their role as guardians of the philosophy of the light side.

The quick and easy path: the Empire

In AotC, Anakin makes an argument for dictatorship as a means of uniting the galaxy and doing what is best for its people. He downplays his comments as a joke, but in RotS this playful moment takes on sinister overtones. On Mustafar, he tells Padmé that he can overthrow the Emperor, and that together, he and Padmé can “make things the way we want them to be”. It is at this point that Padmé draws away from him, and her heart breaks. The woman who has devoted her life to creating harmony in the galaxy through empathy and negotiation has been betrayed, ideologically, by her own husband, who now seeks power and control. I would argue that Padmé’s death because she has “lost the will to live” does poor service to a character that has shown such a strong will. However, on a thematic level it makes a certain sense, and not just because of its fairy-tale overtones: Padmé’s heart is broken because the Republic, the great cause of her life, has finally been destroyed by the person she loved the most.

At the end of RotS, Padmé’s funeral on Naboo is attended by Jar Jar and Boss Nass. The cooperation and harmony idealised in TPM has died, and their voices were too small to overcome the selfishness and corruption infesting the Republic.

By submitting to their fear of chaos and handing unlimited power to Palpatine, the Senate is in effect falling into the dark side itself by taking what Yoda calls in The Empire Strikes Back “the quick and easy path.” Rather than take the more difficult road of rebuilding the Republic in a fairer way, piece by piece, through empathy and understanding, they instead turn to totalitarianism to unite a divided and war-torn galaxy. Though the prequel trilogy shows us how easily a democracy can fall into decay, it also warns us not to give up on it, because the alternative is far worse. As Queen Jamillia says in AotC, “the day we stop believing democracy can work is the day we lose it.” We see again that Lucas’s political philosophy reflects the wider themes of his Star Wars – Anakin, too, takes the quick and easy path to power to solve his problems, instead of following the more difficult and selfless Jedi path.

Imposing order from above – even in the guise of a benevolent dictatorship, as Anakin invokes in AotC – is fundamentally against Lucas’s ideology. Harmony is not something that can be enforced by military power; it must arise from empathy and understanding between beings.

The Empire is not a comment on any specific dictatorship. There are elements of communism in its attempt to nationalise commerce and agriculture – Biggs refers to this in a deleted scene in A New Hope, and the idea has been further explored in Jason Fry’s Servants of the Empire series. However, the militaristic patriotism of the Empire more closely resembles the fascist regimes of Mussolini’s Italy and Hitler’s Germany. Palpatine’s regime is a hybrid totalitarian state, and its only ideology is order. Lucas is not making a point about any particular regime, but about the very concept of totalitarianism.

The Empire’s invocation of order and justice is, in any case, a lie. We see throughout the original trilogy that the criminal underworld now works in partnership with the Empire. Darth Vader is happy to employ bounty hunters to do his dirty work, and to help out Jabba the Hutt in the process. Marvel’s Darth Vader comics have since explored this idea further. Where the Republic failed to combat slavery and criminality through self-interest, the Empire actively uses them as a means to consolidate its own power, without a care for those who will suffer. In Return of the Jedi, it not just the Emperor who falls, but also Jabba the Hutt, and we must ask ourselves if the celebrations we see on Tatooine at the end of the film are more due to the latter than the former.

As the Empire falls in RotJ, Lucas’s story comes full circle. While Imperial forces attempt to subjugate the forest moon of Endor through military might, the Rebel Alliance achieves victory by uniting with the native Ewoks. Leia is kind to Wicket, just as Padmé was kind to Jar Jar, and the rebels show humility, becoming part of the Ewok tribe. The Ewoks, in turn, agree to help them. It is this cooperation between peoples – and the Ewoks’ harmony with their natural environment – which overcomes the Empire’s clumsy militaristic power, and brings us right back to the Battle of Naboo. At the same time, above Endor, it is Luke’s empathy and compassion for his father that reawakens the good inside Anakin Skywalker, who sacrifices his life for his son. As Lucas’s saga ends, the Naboo and Gungans celebrate together, on the same street where they held their parade at the end of TPM, while on Coruscant, we glimpse the Jedi Temple and the Senate building for the first time since RotS. Harmony has been achieved once again, and the Jedi, and democracy, have returned.

New Republic, new problems

George Lucas has since handed Star Wars to other storytellers, and it is impossible, without further information, to judge just how much of his treatment for the sequel trilogy survives. Where Episodes I-VI and The Clone Wars were driven by the political outlook of one person, we have now entered an era where stories are created by committee. I would argue, however, that the newest books and films have been consistent with Lucas’s beliefs, but have approached them from a new and interesting angle.

The Force Awakens is light on politics – arguably too light – but the real insight into the New Republic can be found in Claudia Gray’s Bloodline. On the positive side, Luke Skywalker appears to have disentangled the Jedi Order from its role as a peacekeeping force for the government, and taken it back to its origins, as he researches the early Jedi and trains his apprentices far from the center of galactic politics. However, in the Senate itself, the outlook is less optimistic.

After decades of peace, the Republic has split into two parties – the Populists, who believe in greater self-determination for member worlds, and the Centrists, who argue for a stronger centralized power. Neither side is willing to compromise with the other on any issue, leading to gridlock in the government. Only two Senators – the Populist Leia Organa, continuing the legacy of her mother, and the Centrist Ransolm Casterfo – forge a path of cooperation, as they work together to investigate corruption and criminality. However, as with Padmé’s attempts to save the Republic, Leia and Ransolm’s work ends in tragedy, as dark forces destroy them, and some Centrist worlds ultimately secede from the Republic to join with hidden Imperial forces and become the First Order.

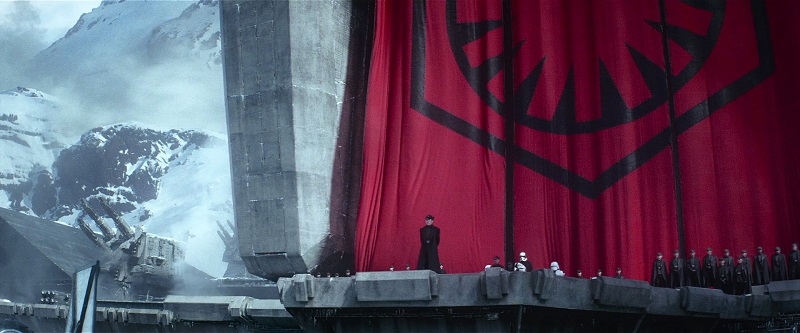

Many Centrists are loyal to the old Empire, a political system which stands strongly against Lucas’s philosophy. However, Bloodline introduces us to another danger – that of partisanship. Both sides are unwilling to compromise their beliefs and work together for the overall good of the galaxy. It is in this environment that the extremism of the First Order is able to gain a foothold, and when the Centrists find themselves unable to change the Republic through democratic means, they decide to leave and ally with old Imperial forces instead. The Republic, now controlled by Populists unwilling to risk military conflict with the First Order, is destined to fall.

The beliefs of the Centrists may stand against those that Lucas valued – the First Order certainly does – but Bloodline shows us the danger of failing to have empathy for those with different beliefs. A kind of selfishness is once again at the heart of it – a dogmatic belief that our own opinion is the correct one, and that we must not compromise any of our ideology.

Episode VIII and beyond

If Star Wars has a political message, it is that democracy can fail through self-interest and partisanship, but that we must never turn to dictatorship to fix it. Instead, politics must be grounded in humility and empathy – as displayed by Padmé and Leia – if it is to make a positive difference in the world and bring about true harmony. This reflects the overall philosophy of Lucas’s Star Wars – that greed and the desire for power lead to the dark side, while compassion and selflessness keep us in the light.

Much of the political intrigue in Bloodline came directly from Rian Johnson, so we might anticipate a greater emphasis on this element in Episode VIII than we saw in TFA. If the New Republic has survived in any form, we should not expect it to solve the crisis – indeed, its dogmatic and uncompromising approach to politics may have turned it into little more than a lesser evil than the First Order, with General Leia’s Resistance, and Luke’s new Jedi order, caught between the two.

So how will this war be resolved? Based on the previous films, we might expect the final defeat of evil in Episode IX to come about via empathy and harmony between different societies. But with George Lucas no longer part of Star Wars, this might not take the form of our heroes uniting with creatures such as Gungans or Ewoks. If the themes of Bloodline are to be explored further, it may be political forces, and differing ideologies, that we see reaching an understanding. And this theme may again be a reflection of the larger theme of the trilogy as told through the struggle between the light and dark sides of the Force. The TFA novelization by Alan Dean Foster begins with this poem from the Journal of the Whills:

First comes the day

Then comes the night.

After the darkness

Shines through the light.

The difference, they say,

Is only made right

By the resolving of grey

Through refined Jedi sight.

The “resolving of grey” indicates that a third way can be found, and this might apply on both a political and a personal level. Perhaps our new protagonist and antagonist – Rey, a beacon of light who feels the pull of the dark side during combat; and Kylo Ren, the darksider who feels the seduction of the light – will eventually come to a mutual understanding, and an empathy for each other’s struggles, and as a result, will succeed in uniting the galaxy once again.

Excellent piece–thanks for writing it!