The last time Jason Fry and I digitally sat down together, The Force Awakens was right around the corner and a deluge of Force Friday books had just swept away everybody’s mental real estate. Even in a two-part interview, it was a huge challenge to cover everything Jason was then involved with in the world of Star Wars without asking a hundred questions. So it was actually kind of a relief that this time the decks were nice and clear—we know he’ll have things coming out this fall in conjunction with Rogue One, but it’s a mite too soon for any real detail on those (hell, even any fake detail).

What, then, should we talk about? Well, he does have one thing coming out just around the corner (June 14th, to be precise), something with a long history of coming up in these interviews of ours—The Rise of Earth, the third book in his original series The Jupiter Pirates. Something that’s also come up a lot is Jason’s advice on designing a world like JP’s from scratch; how that process was informed by his Star Wars experiences, and vice-versa. I know a lot of us SW fans have dabbled in original fiction inspired by our fandom (some, like Bryan Young and Tricia Barr, have even released their own stories and gotten invited to do SW as a result), so I thought rather than do a straight interview entirely about a non-SW series, it would be fun to frame this as sort of a seminar in worldbuilding, covering everything from the first steps to the finishing details, and even post-publishing.

First up we’ll discuss the foundations of the Jupiter Pirates universe—why it is the way that it is—and how they inform the messages present in the work, both deliberate and happenstance. Then in the second part on Wednesday (we’ll be off for Memorial Day) we’ll look at smaller stuff like naming characters, and how to handle errors that come up once a book is committed to paper.

Phase One – Building Blocks

You had almost nine centuries of real-world history to develop between the present and the story of Jupiter Pirates; can you talk a little about why you set it exactly when you did, and how you went about sketching in that huge gap?

I needed an amount of time that seemed sufficient for colonies to get established and create divergent societies, but not so much time that those societies would be completely different, or have escaped dependence on Earth. Granted, you can argue about how long that might take: The wonderful Expanse books by James S. A. Corey do some great world-building around that process, which went a lot faster than in Jupiter Pirates. But I attribute that mostly to the fact that The Expanse is science fiction where Jupiter Pirates is space fantasy.

Similarly, I needed enough time for piracy to arise in the outer planets, have a long “golden age,” and wind up near extinction. I think those are the most fruitful settings for storytelling – when things are in the process of changing, but how things will change is still to be determined. You get a lot of conflict, and a chance for your characters to shape events.

Similarly, I needed enough time for piracy to arise in the outer planets, have a long “golden age,” and wind up near extinction. I think those are the most fruitful settings for storytelling – when things are in the process of changing, but how things will change is still to be determined. You get a lot of conflict, and a chance for your characters to shape events.

That was the end state in terms of storytelling; from there I worked backwards to figure out how much time I needed.

Working backwards is one of the storytelling tricks that aspiring writers should learn first, because it’s so simple that it almost feels like cheating. There’s a great bit about that in the story sessions for Raiders of the Lost Ark: the end state is Indy and Marion getting flung into a temple full of snakes, and the working backwards is having Indy talk about hating snakes earlier in the movie, all the way back to the harmless one in his lap. It feels magical to the moviegoer or reader: elements get introduced and build up to a payoff. But the storyteller feels a little sheepish at the applause, because he or she got to run the tape in reverse and make everything come out right. The process works whether you’re talking about action scenes in a movie or crafting fictional history for a book series.

As for filling in the blanks, I learned from my Star Wars experience and kept things pretty loose, sticking to what would come up in the conversations the Hashoone kids would naturally have with each other and with their parents. This way you get bits and pieces of history, but they’re anchored to incidents in family lore, unfold as part of pirate tales, or come up in battle simulations.

I tried to stay away from the dreaded “info-dumps,” not always successfully. There are a couple concerning the Battle of 624 Hektor, but that event was the turning point for the pirate tradition and the Hashoones’ family fortunes, so those info-dumps seemed like a necessary evil, and I tried to make them go down easy by delivering them through the kids arguing. That way those scenes did double duty as character development. (That’s another great basic writing trick: instead of two scenes that each do one thing you need, find a way to make one scene do both.)

For fans of the series and to scratch my own world-building itch, I had Tycho write a homework assignment about the history of the solar system – it’s an exclusive for members of the Crew, the Jupiter Pirates mailing list. Some of the events Tycho talks about in that paper get revisited in The Rise of Earth: he meets Kate Allamand, a young woman from Earth whose view of the Jovian Union’s grievances is quite different than his. And once when we get to Earth later in the series (probably Book Four), that history will be highly relevant in understanding why Earth works the way it does.

A few folks who’ve read Tycho’s paper have complained that Vesuvia takes some points off Tycho’s grade because he got a few dates wrong, but she doesn’t say which ones. That was deliberate—it’s my Get Out of Continuity Jail Free card, should I ever need it.

Compared to Star Wars, the technology of Jupiter Pirates is fairly grounded—what would you say is the least plausible invention (or event) you had to posit to make your premise work? And more broadly, how do you even approach “plausibility” in worldbuilding? Did you feel any responsibility to detail a future for Earth that felt politically, militarily, and/or technologically realistic? Very little of the Jupiter Pirates universe seems fantastical to me, so the contrast with the total insanity of Star Wars stands out.

I don’t think there’s an individual invention or event like that – it was more the initial choice to write space fantasy vs. science fiction and not worry about the implausibility of the space-fantasy elements. Jupiter Pirates has what I call Lucasian physics: ships dogfight, get lost, hide behind asteroids, etc. I took that approach because I grew up loving Star Wars and wanted that same feeling animating my stories.

I think what you’re responding to is that Jupiter Pirates doesn’t have aliens, robots or faster-than-light travel – the farthest we see anyone travel (so far) in the series is Saturn. I’m also proud of the fact that there’s life on Europa (and other places too) but nobody talks about it because it was discovered centuries ago and doesn’t really affect anyone’s life. Which I think is realistic: tube-worms in Europe’s ocean would be a game-changing discovery in 2016, but by 2816 most people wouldn’t care.

The funny thing is, the decision about what to exclude was also shaped by Star Wars. I love aliens and droids and hyperspace, but I’d worked with that palette and wanted to do something different.

Writing within those limits also helped me tell the story I had in my head. The Earthfolk and Jovian Union loyalists and Saturnian revolutionaries are all stuck with each other – they can’t just fire up the probability drive of a colony ship and find another star system. I didn’t think about that consciously, but it fit. That’s often true with storytelling – a lot of the time you’re navigating by feel, and have to trust yourself that there’s a reason you chose Door No. 1 instead of Door No. 2.

The plausibility question is an interesting one, and one I have to admit I’m still wrestling with. I’ve said before that for me world-building is like matte painting: you don’t do entire canvases, but limit yourself to the little bits of scenery behind the action. I get why some fans love world-building — I mapped half of a fictional galaxy, so I definitely have that gene. But for me the world-building is always secondary, even tertiary, to the characters and the action. I think if that dynamic gets reversed you’re courting trouble.

This is a really inefficient route to saying that I start with the end state – the characters and the story – and work backwards to make sure the world-building supports whatever circumstances the characters find themselves in. I think what I mean will be clearer when we finally see what Earth is like in Jupiter Pirates. I’ve had some of those scenes in mind for years now, and the world-building has been crafted to support them once the story finally catches up.

Phase Two – Themes and Subtext

It’s hard to escape the sense that a lot of Jupiter Pirates comes from a personal fondness for traditional pirate yarns and wanting to do your own spin on them—but to what extent would you say there’s an underlying message or theme to the story? Do you think every work of fiction has, or should have, a point of view beneath it?

I don’t know about “should,” but I think any story that’s longer and more complicated than a barroom yarn will automatically have a point of view – the presence of a storyteller guarantees one.

Any story that’s compelling enough for you to write it down, commit it to film, etc. is going to come from a bunch of different wellsprings. Stories that moved you will be in there, alongside ideas that intrigued you. Whatever you’re wrestling with in your own life will get in there too, sometimes in odd ways. We’re all remixing and mashing stuff up all the time – it’s what we do.

I love pirate stories, but Jupiter Pirates is probably most influenced by the Patrick O’Brian books and The Sopranos. The setting’s essentially the former, while the family conflict was shaped by the latter, but shifted forward a generation: Huff Hashoone is the unreconstructed pirate, the kids are training to be legal privateers, and Diocletia Hashoone is stuck in the middle – she’s the Tony Soprano of the family.

To that, though, I added my own insecurities about my place in life and in my family. For example, I’ve written my whole life, but have always been conscious of being the son of two very good writers and the grandson of a great writer who’d been a successful novelist. I was raised by one tough, no-prisoners woman and married another, and it took me a while to realize that wasn’t typical. I have no siblings but have always had friends who felt like brothers and sisters.

To that, though, I added my own insecurities about my place in life and in my family. For example, I’ve written my whole life, but have always been conscious of being the son of two very good writers and the grandson of a great writer who’d been a successful novelist. I was raised by one tough, no-prisoners woman and married another, and it took me a while to realize that wasn’t typical. I have no siblings but have always had friends who felt like brothers and sisters.

What are the themes of Jupiter Pirates? I’d say the biggest one is earning your place in your family, and what happens when you start to question whether what you’ve worked for is really what you want. All three of the Hashoone kids reach conclusions about that question in The Rise of Earth, and have very different answers. But that theme wasn’t something I could have articulated when I started planning the series – it bubbled up from all the influences and personal stuff cited above.

Do you feel any responsibility to present the Hashoone kids as role models, considering the books are aimed at younger readers? How do you balance creating three-dimensional child characters (I have a feeling Yana would tell me to go to hell right now) with presenting a story that young minds will absorb constructively? I’m not even sure what I mean by that, but I’m curious whether this is something you think about at all considering that you’ve historically dismissed the idea that “young readers” books are all that different from “adult” books.

Not really. Tycho did some things in Curse of the Iris that made him pretty uncomfortable, and he’ll find himself facing another tough choice in The Rise of Earth. (Oh, and just wait until you see what Diocletia does.) But that’s part of Tycho growing up – when the series is complete, I hope readers will look back at The Rise of Earth and point to things that happen in it as precipitating events for a lot that happens later.

On the other hand, Tycho’s a good person even when he makes questionable choices. I’d say I feel a responsibility to have the protagonist be a good person, but I think that’s pretty close to an ironclad rule in storytelling, regardless of whether you’re writing for kids or adults.

You don’t have to do it that way, but it’s like fighting gravity: protagonists can make mistakes and bad choices, but if they deliberately do wicked things you’re almost daring the audience to bail out. The Ripley books by Patricia Highsmith are an example of storytelling that flouts that rule — they have a weird dread to them because the protagonist is the murderer and the narrative railroads you into rooting for him to escape justice. Those books work because Highsmith’s a terrific writer, but they’re an uncomfortable experience. I suppose that’s true of the Verhoeven movie version of Starship Troopers, too, but the satire hides it better.

It’s actually pretty interesting that you say protagonists being “good people” is so important, because that immediately called to my mind the antihero trend in lots of recent television—initiated, many would say, by Tony Soprano. Do you think you’re skirting that rule because your own particular “Tony” isn’t the story’s focus? And is Sopranos another example of writing that’s just plain good enough to get away with an antihero, or do you have a more expansive definition of “good” than I do?

You’re right that the generational remove lets me skirt it. Another aspect of Jupiter Pirates that lets me do that is Tycho’s age. I like to write “on the shoulder” of my protagonists, generally sticking with their point of view throughout the narrative but maintaining a little bit of authorial distance at all times — I find that little gap can be interesting for both the reader and the writer. At twelve, Tycho is such a product of his upbringing and his environment that the reader notices aspects of Tycho’s world that are invisible to him. But as he gets older that’s less true — he questions more things and entertains doubts he’s never had.

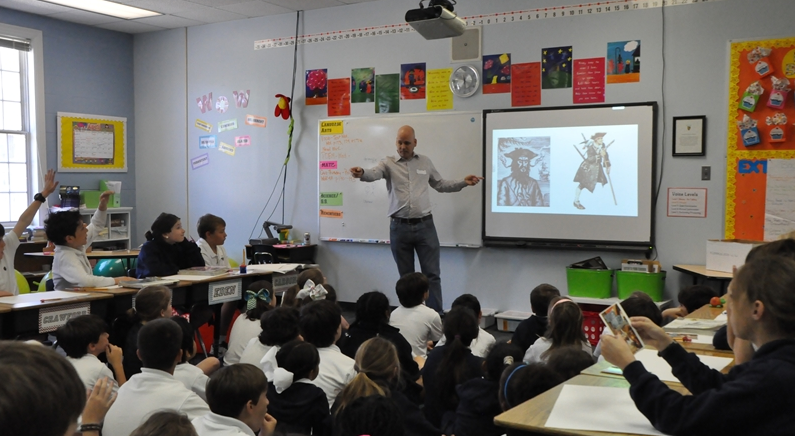

Also, while I hope I’ve never been too cute about this in Jupiter Pirates, I like constructing stories you can engage with at multiple levels. You can enjoy Jupiter Pirates as a pirate yarn; you can also read it that way while musing that Tycho’s part of a troubled society and a family that’s done some shady stuff, and wondering if he realizes that and wanting to know how he’ll react if/when he does. One thing that makes me happy is it’s too simple to say that the pirate yarn is for kids and the sociological musings are for adults. I’ve had conversations with twelve-year-old Jupiter Pirates fans who had a hundred questions about the Jovian Union’s class system and how last names work in 29th-century families, and I’ve had conversations with forty-five-year-old Jupiter Pirates fans who wanted Huff to get his Captain Hook on even more than he does. (Plus folks of all ages demanding to know what’s up with the ship’s cat.) I’m thrilled to have any of those conversations.

* * * * *

That’s all for now! Come back for Part Two on Wednesday!

One thought to “Worldbuilding 101 with Jason Fry”

Comments are closed.