As a general rule, I try to stay away from retrospective pieces here at Eleven-ThirtyEight. Sometimes, like with David’s excellent Jaxxon piece on Monday, there’s a new hook that makes old information freshly relevant, but by and large my feeling is that Star Wars material released prior to the Disney era—and certainly the original trilogy in particular—has had its time in the sun and continuing to poke at it years or decades later is tantamount to navel-gazing and doesn’t really advance the conversation. That can be fun, don’t get me wrong—but it’s not something I’m interested in doing here.

Sometimes, though, new stories create a fresh context for that old material. Luke’s behavior in The Last Jedi might create a new lens through which to view his training, for example, or a pending film might prompt the revisitation of related material from the Expanded Universe. Even if you discount Legends, Star Wars remains a gigantic body of work and there are always new threads, new patterns, that can be isolated when the moment is right.

Despite the scattershot nature of the eight saga films’ release timeline, despite being written out of order and across multiple generations and largely on the fly, one such thread has lingered in the background since the very beginning. It has a logical starting point in Episode I, pays off in Episode VI, and most impressively, continues in a sensible and compelling way in the sequel trilogy—all with very little in the way of open acknowledgement from the creators. This thread, to my mind the great unspoken subplot of Star Wars, is the quest for the perfect soldier.

Our story begins with the Galactic Republic. In a time of ostensible peace, the government has no standing army. Average citizens—especially in the Core—signing up to fight on its behalf is an unthinkable concept. The first army we are introduced to is quite literally a commodity: privately owned and operated battle droids, fighting for the interests of their owners. Little more than blasters with legs.

There are two spectra we’ll be keeping tabs on throughout this story: effectiveness and uniformity. Battle droids represent the bottom end of the former spectrum and the top end of the latter. To the casual observer, they’re bloodless, G-rated chaff for the heroes to mow down in what’s reputed to be the least “mature” Star Wars film. Even the sarcastic sense of humor they begin to exhibit in later films and in The Clone Wars is handwaved as malfunctioning circuitry—they’re centrally controlled and have no internal lives, so any semblance of a personality is purely coincidental. And yet…

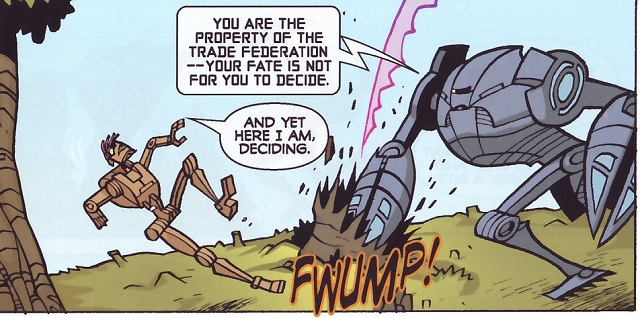

L-1

Our first subject has no official designation—Wookieepedia identifies them simply as “Lone battle droid“, in honor of which I’ll be referring to them as L-1 (get it?). In the short comic story “Pathways” by Jeremy Barlow and the Fillbach brothers, L-1 is separated from their unit in the heat of battle on an unnamed planet. Damage from a land mine severs their connection with the central control core, and almost immediately a personality emerges. L-1’s new awareness is guided by one new principle above all: self-preservation. One droid couldn’t make much difference in a conflict of this scale, so why walk willingly back into the line of fire?

After narrowly foiling another droid’s efforts to retrieve them, L-1 resolves to spend their dwindling battery life relaxing under a tree and savoring the lack of conflict—“I’d rather have two days of freedom”, they conclude, “than go back to what I was.” Years later, a depowered L-1 is found by two locals and put to work on their ranch, where one can hope war never touches them again.

Was L-1’s personality always present and simply overridden by the control signal, or were they born on that battlefield? Either way, the ramifications are unsettling to dwell on. But the story of L-1 posits that you can never completely control for free will, that no degree of regimentation is immune from chaos theory.

* * * * *

Anomalies aside, the battle droids served their purpose. In sufficient numbers, they gave the galaxy’s corporate powers enough confidence to mount a secession movement against the Republic, thereby justifying in the minds of the Senate (and, alas, the Jedi Order) the massive clone army Darth Sidious had already created.

With their development being a major plot element in Episode II, the Grand Army of the Republic is the closest this “perfect soldier” subplot ever comes to being explicitly stated. Where battle droids were cheap and disposable, the clones are bespoke soldiers, made from the finest genetic template available and custom-augmented to the Republic’s needs. And indeed, they were “immensely superior” to battle droids, as Lama Su boasted, holding their own despite being outnumbered something like a hundred to one.

But while they started out effectively identical, even a bunch of genetic duplicates couldn’t help but develop distinct personalities. More chaos theory, perhaps—the travails of war and the dynamics of brotherhood worked their magic, and by war’s end, any number of veteran clones were walking around with given names and riotously customized armor that would have made Sabine Wren proud. Perhaps Sidious had planned for this all along, or perhaps he saw what was happening and reacted accordingly, but when it came to the clones’ most important order, this amount of invididuality was dangerous—and thus extra measures had to be taken.

CT-5555

As one of the primary recurring characters on The Clone Wars, the unimaginatively-named Fives is the quintessential clone “success story”. He begins as just another buckethead off the assembly line before finding his way into the 501st Legion under Anakin Skywalker, and after displaying an uncanny talent for not dying is promoted to the ranks of the special-forces ARC troopers.

ARC trooper Fives is present at the Battle of Umbara under Jedi General Pong Krell, who turns out to have gone rogue—as a gesture to Count Dooku he leads his clones into one death trap after another, effecting heavy casualties before being discovered and put down. The Umbara episodes are clearly meant to communicate to the audience a rising discomfort with the Jedi on the part of certain clones—Anakin’s unit in particular. We leave this arc beginning to understand what might have been going through their minds while executing Order 66 some months later, but we still don’t have the full picture.

Soon after, Fives witnesses Tup, a fellow clone, experience some kind of mental break and assassinate his Jedi General. Fives takes it upon himself to investigate the incident, eventually discovering an artificial chip implanted in Tup’s brain—and presumably other clones’ as well. Fives never figures out the whole story, but we of course recognize that the chips are meant to ensure compliance with Order 66.

The Expanded Universe notably went a different direction on this subject, explaining that the clones’ obedience conditioning and trust in the system were enough to ensure the vast majority followed through. I admit to preferring this interpretation myself, but Darth Sidious was nothing if not thorough—and thus I’m happy to accept a number of clones (those serving alongside Anakin and Obi-Wan would naturally be prominent candidates) were outfitted with chips as an extra level of security.

In any event, Fives’ inquiries eventually attract Sidious’s attention and he is dicredited and disposed of, but not before warning Rex, his brother in the 501st, that something was amiss—and sure enough, when Rex is found by the Rebels many years later he and his companions have removed their chips, and thus avoided participation in Order 66. Unlike L-1, Fives’ exercise of free will makes a material difference in both the Clone Wars and the Rebellion.

* * * * *

With the Clone Wars having done their job, the newly-minted Emperor decides to phase out the clones in favor of conscripting soldiers from across the Empire. The throughline of this subplot now becomes clearer: clones were much more effective than droids, but ironically, their personalities were too distinct; chips or no chips, they weren’t manageable enough—and as soldiers through and through, they likely would not have taken well to quiet garrison assignments in the middle of nowhere.

Thus, Sidious willingly turns down the effectiveness dial in order to also turn down the autonomy dial. He no longer needs warriors as much as he needs legions of faceless, innumerable goons to reinforce the idea that his Empire is always present, always watching. Brainwashing and dehumanization become the rules of the game, and surprisingly, it proves easier to brainwash impressionable proles than custom-bred warriors.

Those proles are, of course, famously terrible soldiers—by now, one begins to get the impression that Star Wars is trying to tell us something.

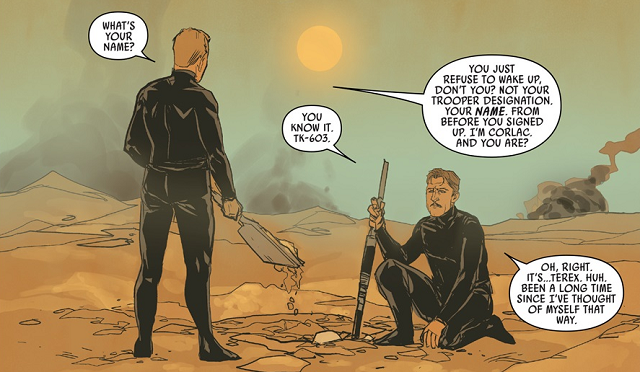

TK-603

Where the clones started out with designations and chose names, stormtroopers are born with names, families, and regular lives, and voluntarily forsake them all. One such trooper was TK-603, a survivor of the Battle of Jakku we meet in Charles Soule and Phil Noto’s Poe Dameron comics. When it becomes clear the Empire has lost the battle—and the war along with it—TK-603’s companion TK-605 shoots their commanding officer, offering an explanation uncannily reminiscent of L-1’s: “I didn’t particularly feel like fighting to the last man.” Reintroducing himself as Corlac, TK-605 appears thrilled to leave it all behind, whereas TK-603 needs a moment to even remember his real name—Terex. The two then spend a year in the Jakku wastes, cobbling together enough damaged ships to finally leave the planet. But even after all this time, Terex brings his stormtrooper armor with him.

The two link up with a criminal enterprise on the planet Kaddak, but while Corlac has visions of piracy and general criminality, Terex maintains hope that the Empire will “come back”. Corlac and his associates convince Terex to use the access codes from his former post at the Rothana Imperial Shipyards to gain access to a treasure trove of old hardware—but where they see a pirate fleet, Terex sees the beginnings of a new Imperial fleet: if you want something done right, you might as well do it yourself.

After months of work, Terex eventually overhears Corlac lamenting Terex’s delusions of a reborn Empire and promising to take him out of the picture when their plans inevitably conflict with his. In this moment, at long last, Terex accepts that the Empire is over, killing his co-conspirators and spending the next couple decades as a surprisingly effective criminal himself. But even then, some part of him never lets it go, and when he eventually learns of the First Order, the faceless-grunt-turned-warlord doesn’t hesitate to leave it all behind and reenlist.

* * * * *

Effectiveness and uniformity, it seems, are at odds in this universe. Just below the surface, the saga portrays an ongoing push and pull between good soldiers and submissive soldiers, and in this light the routing of the Emperor’s “best troops” by a bunch of teddy bears represents a satisfying final statement: no tactical or technological advantage can compete with a diverse group of individuals fighting of their own free will.

Terex encapsulates this point nicely—he begins as a grunt, but the more he’s able to shed that mentality, the higher he rises. Even when he returns to service, he does so as “Agent Terex”, having earned through force of personality a degree of self-determination. It says everything that when he falls too far out of line, his punishment isn’t imprisonment or execution, but mind control.

But I’m getting ahead of myself—with the development of the sequel trilogy, the Battle of Endor would prove not to be the final statement after all.

FN-2187

At first glance, First Order stormtroopers are the optimal solution to the problem of the perfect soldier: trained from birth like clones, brainwashed like stormtroopers. It’s actually pretty remarkable what a logical next step this is, and it suggests the people writing these films are paying closer attention than many give them credit for.

And yet! Even with no loved ones to lure them away, with scarcely any awareness of life outside the First Order at all, the very first we see of these terrifying new stormtroopers is a desertion. The instant he’s dropped into combat for the first time, something inside FN-2187 just understands that this isn’t what he wants, and before you can say “stormpilot” he’s out of there.

Rebranded Finn by fellow escapee Poe, FN-2187’s real fight is just beginning: through Rey, he learns for the first time what it means to really care about someone else. Maybe a little too well, in fact, as his motivation for the next film-and-a-half is not defeating the First Order but protecting Rey. Only when she leaves for Ahch-To and he’s deprived of this option does Finn have an opportunity to consider the needs of the galaxy at large.

With Rose’s guidance, and with DJ as a galling example of the other direction his life might take, Finn at last embraces the Resistance’s cause independent of his concern for Rey. In his final confrontation with Phasma (for now?), she dismisses him as “a bug in the system”, inherently flawed, never better than scum. “Rebel scum”, Finn replies.

* * * * *

Even in the First Order—hell, even in battle droids—individuality appears to be inevitable. That seems to be this thread’s real message: regimentation is anathema to personhood. No matter how completely you control for free will, life finds a way.

But what of it? If that’s what the story is trying to tell us, what endgame does it suggest for all those other stormtroopers?

In a scene deleted from The Last Jedi (but preserved in the novelization), Finn learns that his former allies on the Supremacy aren’t aware of his actions—a successful desertion (by now a full defection) is regarded as a dangerous idea, and the First Order was careful to keep it quiet. For all the foaming zealotry of an officer like Hux, the average stormtrooper may not be as devout as we think.

The cleanup of the Empire has been a hot-button subject over the last couple years, given the later atrocities of the First Order. Could more aggressive penalties for former Imperials have scared people like Terex straight? Considering the state of affairs after Hosnian Prime is destroyed, the case could be made that the New Republic shouldn’t have left so much as a single stormtrooper alive. But I don’t think that’s the lesson we’re meant to learn here—my suspicion is that in the end this great unspoken subplot will at long last dovetail with the saga’s primary lesson: compassion.

However many Episodes we end up getting in the future, no amount of star warring is going to account for every single stormtrooper. When the First Order is defeated, what do you do with all those people? If a conscript like Terex can’t learn his lesson, what hope is there for someone raised the way Finn was, with no home to return to? I honestly have no idea. For a while now I’ve had an image in my head of a true final battle involving rebels and stormtroopers fighting side by side against…something. I don’t know what, nor do I know if there’s a way to do that in the current political climate that doesn’t come across as irresponsibly forgiving of real-world fascism. But the story Star Wars keeps choosing to tell us over and over is that people are not meant to be stormtroopers—and good guys can come from anywhere.

It may not be worth revisiting the entire piece for a few lines of dialogue, but Hux makes an extremely interesting comment on Crait before Luke and Kylo fight. I won’t say anything if you plan on reading it soon, though.

I’ll get back to you in a few days then. 😛

Having read that scene now, I honestly wouldn’t read a lot into the Jedi thing—he frames them as child warriors is based on Brendol’s warped version of history. I do think there’s meat in the notion of neither Jedi nor clones (nor FO stormtroopers) knowing their families, versus Luke and the Rebels coming from loving families, but that could be another piece entirely.