The Last Jedi is my favorite Star Wars movie. I could gush about it all day. Canto Bight, Rose, D’acy, the duel on Crait, Finn and Rey’s hug, the scene in the novel where Rey and Luke dance, the themes, the emotional release, the technical prowess of it all. Marvelous! But for all that, there’s one scene in which I find no joy.

It feels a little odd. I’m looking at something that’s a technical and choreographic marvel, at something where the actors deliver stunning performances, at something that hits the right emotional beats of a story, both in its own subplot and in the interwoven narrative of the movie as a whole. I’m looking at such a well-executed scene in my favorite Star Wars movie, and I cannot like it. I have never liked it. Not the first time I watched it, not the last.

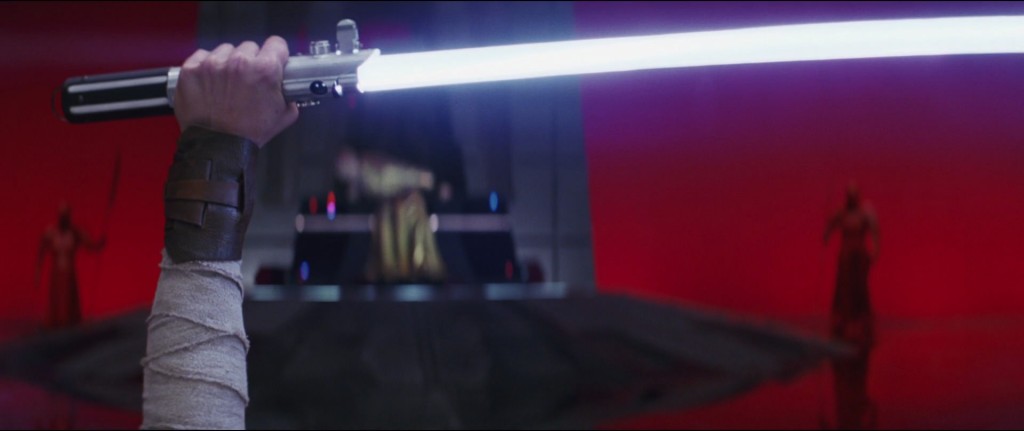

I don’t like the throne room battle sequence.

It’s purely an emotional reaction on my part, I can admit to that. I dislike the throne room battle on a gut level. And that’s okay, because emotional reactions are a critical part of the conversation around this movie. If we’re not honest about our emotional reactions, we’re not going to get anywhere.

Three Disclaimers

This is not a defense of sexist, racist, homophobic, etc. reactions. They do fall under emotional and non-rational reactions, and it’s important to examine yourself and society to see if certain emotional reactions are toxic. It’s important to have a conversation about them. That does not make them valid.

This is not to paint all criticism of a thing – in this case: The Last Jedi – as purely emotional, as I feel Film Crit Hulk did in his otherwise-incredible article: The Beautiful, Ugly, and Possessive Hearts of Star Wars.

[Hulk’s conversation partner] finally just yelled, “I felt like the film was making fun of me!”

And there it was. All these things that I’ve been talking about. The feeling of “being talked down to” by Holdo. The not wanting Finn to be silly. The ignoring of character arcs, the silly tone, the faux logic arguments, it all adds up into the vicarious way people place themselves into a movie. So they felt attacked by this movie…but it’s not attacking them, it’s attacking qualities of people. It’s attacking toxic masculinity. It’s attacking toxic fandom. It’s attacking all the worst parts of ourselves and asking us to do better. (emphasis mine – Abigail)

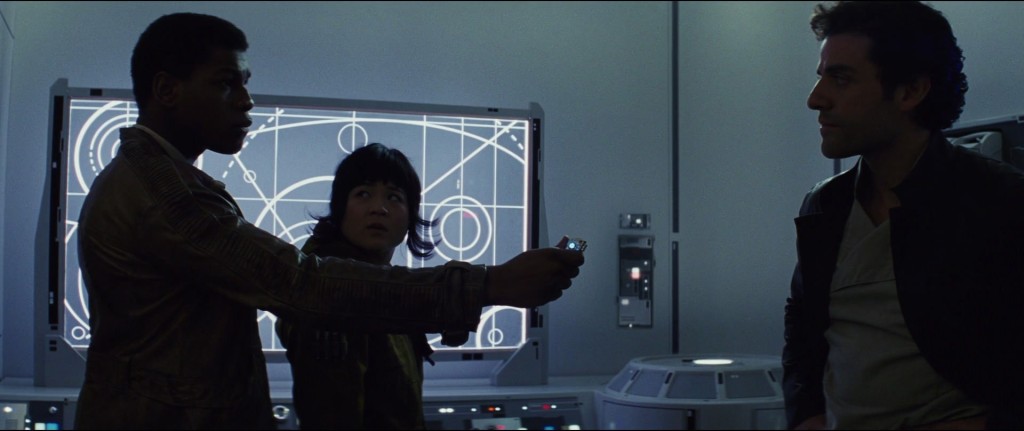

I don’t disagree with Hulk’s conclusion here as it pertains to masculinity or film criticism in general. In fact, a lot of this essay is going to be agreeing with Hulk. But not all who had an issue with Holdo and Poe’s dynamic or Finn’s slapstick comedy were upset because it was a man (gasp!) being corrected by a (gasp!) woman. There’s a racial element here too: it’s a Latino man being talked down to by a white woman. It’s a black man getting slapped about for comedy. It’s not just wishful indulgence on the line; it’s historic, on-screen representation. Representation is about more than just giving someone a positive emotion; it shapes worldviews for good or bad, and white people like us don’t get to tell people of color what is or is not “good representation”.

This is not an attack on other fans’ preferences or interpretations of The Last Jedi. Loaded language will be used in my reflections because I had a loaded emotional reaction. This loaded language is directed at the movie and fictional characters, not at fans or at creators at Lucasfilm. I do my best to avoid areas of fandom whose interpretations will cause me to react in such a way at fellow fans who are, more importantly, fellow human beings.

So, to reiterate:

This is not a validation of toxic responses to things. This is not a dismissal of all criticism of a thing I like as emotional. This is not an attack on other fans or their interpretations.

This is simply to say: your reaction to something can be purely emotional, and that is valid.

My Life Flashing Before My Eyes

I did not like The Last Jedi on my first viewing, not until after the throne room battle was done and Kylo showed his true colors once more. Every scene afterwards was a cathartic release of all the dread and revulsion that had been slowly stacking in my chest since Rey and Kylo’s first connection.

I did not know where they were going but a single end result seemed to loom large in my mind: Rey would become an emotional crutch for Kylo, and so he would be redeemed. And I would be expected to cheer at her sacrifice.

I did not realize until the cathartic release came, until after The Last Jedi cemented itself as my favorite Star Wars movie, why it had all been so visceral.

As with Rey and Kylo, it wasn’t romantic. There was an intimacy there, yes, but it was never romantic between us. My friend and I once stole away to a beach together to sort out old pains of ours, watched the sun set, and laughed about how between any other two people, it would have been romantic, but wasn’t it nice that we were able to share it as just friends?

We became friends in the same way that Rey and Kylo did. A shared loneliness, a feeling of being outcast from the very people who were supposed to welcome us with open arms: our body of faith. A friend to whom one could say “you’re not alone” and hear the same in return. In that way, we told each other our pains and fears. I remember telling him that I was afraid of the fact that I related to a specific villain character, because I was afraid that it meant I was cowardly and traitorous.

That was especially hard to admit, especially to him. I had initiated the friendship because we had similar interests, but I threw myself fully into it because he revealed he had cut himself off from his faith-support system and mourned its loss. I thought I could be the one to bring him back. I thought I could save Kylo Ren. And I became convinced that I had an obligation to do so, no matter the toll it took on me. I was no traitor. I was no coward. And I would not abandon him like everyone else did.

The Last Jedi paints out, beat-for-beat, my friendship with him. The one-sided stories that cast people I respected as villains and himself always the victim. The warnings from those familiar with his past. The philosophical lecture about parents meant to bring me to his side. Increased isolation that refused to share my friendship with others: it was him or them. Heck, I even had described my support to him in a manner that echoes the throne room battle in eerily specific ways (we were quite a melodramatic pair).

Our friendship ended in the same way as Rey and Kylo’s in The Last Jedi. After a moment of intense trust – standing back to back in battle, inviting him to my home to meet my family – the isolation tactics become glaringly clear. And maybe Kylo and my friend didn’t even realize that they were doing this, maybe it wasn’t their intent, but the result was the same.

A demand for even more emotional entanglement, and the realization that you’ve gone too deep. With all your good intentions, with all your hopes, and you find he’s determined to stay down in his bitterness. He doesn’t want out; he wants you to stay there with him.

This has been your life. You have staked your purpose on this, and suddenly it’s get out or drown under his needs and his needs alone.

I didn’t ghost him. I treated him with the respect I felt he was due and went to talk one-on-one. It wasn’t healthy to hang out just the two of us, I told him, but let’s hang out with mutual friends. Rey offered something similar to Kylo: save the fleet, find a group with which to belong again. Let’s step out into the light together.

And for mine and Rey’s efforts, our deepest insecurities that we shared in intimacy were slapped back into our face. Painted in such a manner that the only way out was into the pit with them.

“You have no place in this story. You’re nothing. Nothing. But not to me.”

“Everyone else left me because they couldn’t handle my pain. I didn’t take you for a coward.”

The first time the throne room battle kicked off, I didn’t feel triumph at a man redeemed. I felt sick, as if my friend’s use of me, as if my role as an emotional crutch, was morally right. As if I should not have laid down that boundary. As if I should have kept going until I found the throne room battle that I had once described, regardless of the toll his friendship took on me.

So I felt a strange, sick sort of relief as Kylo revealed his true colors and claimed the title of Supreme Leader. I felt a gentler, cleaner relief as Rey shut the door on Kylo.

I felt ill for days after I had broken off my friendship with him, half believing that I was the coward he said I was. The Last Jedi gave me a balm for this guilt I’d carried. Rey showed me that I wasn’t morally wrong for trying to connect with a fellow outcast nor was I morally wrong for breaking off a toxic relationship. But even with that balm, even knowing the cathartic release that’s coming, I cannot bring myself to thrill at the battle.

It’s a well-constructed scene, narratively placed with aplomb, with stunning choreography and powerful acting. And I loathe nearly every second of it. That sick dread knots itself in my gut all over again, as I wait for Rey’s fears to be thrown back into her face.

“I didn’t take you for a coward.”

Stretch out with Your Feelings

Storytelling, for both the creator and the audience, is a deeply personal thing, and that can be frightening. The creator slips bits of their own life into it, and the audience sees their life reflected. Joys, fears, desires, pain, no holds are barred. Storytelling is visceral for everyone involved, which makes visceral reactions valid.

I can write 50,000 words (and counting) for an essay about “Twin Suns”, using film and literary theory to declare what a masterpiece of storytelling it is, dedicating over 15,000 of those to argue how this was the perfect ending for Maul. Someone else can write a 280-character tweet on how “Twin Suns” made them feel like they were watching a mentally disabled man get put down violently. That gut-wrenching interpretation is no less valid than mine for its length or its emotionally-charged language. They can exist alongside each other, and the conversation is all the richer for them both.

There seems to be a fear among a certain, widespread brand of film reviewers to admit to having an emotional reaction to something. So, like Film Crit Hulk’s conversation partner, they couch their dislike in rational or logic-based language, creating a smokescreen that doesn’t allow any real conversation to take place.

Since this brand of reviewer often gets misinterpreted as film criticism, it changes that conversation as well, which is why we’re seeing a lot of push back from film critics on this subject. Film Crit Hulk talks about it frequently, including in the essay I’ve already linked here. Lindsay Ellis discusses it in her analysis of the Disney live action remake of Beauty and the Beast. Patrick H. Willems spends an episode of his show specifically tackling the most oft-used smokescreen: plot holes.

You can find plot holes or logic gaps in any movie, and if you want to, go right ahead. Just don’t tell me that those are genuine flaws and problems and reasons that a movie is bad. Because they’re not. None of these things actually matter, because they’re not what a movie is about. …We’re so invested in [the characters] that to pick apart the logic… would mean totally disengaging from the story. (Patrick H. Willems: SHUT UP ABOUT PLOT HOLES.)

This brand of film review/criticism creates pressure to give a rational “why” for our reactions to things. This is tied into some use of the phrase “guilty pleasure”, as if we’re not supposed to like something that’s of “poor” quality, so we either must admit out front that we know it’s not that good, or we must find some logical reason to support our opinion. It’s the same with the reverse, like the series of nitpicks about the throne room battle, in which a weapon seems to have been edited out in post. I’m sure I could find a thousand different “rational” reasons to say why I dislike this scene, but none of them would be honest.

One of the most frustrating moments in The Clone Wars is in the final Clovis arc, where Obi-Wan tries to have a conversation with Anakin about his jealousy over Padmé’s former love life. They never get to the heart of the matter because Anakin keeps giving false reasons for his anger, and Anakin keeps giving those false reasons because the current environment of the Jedi Order does not allow for raw, emotional honesty.

Storytelling is going to get raw and honest with us. I’m not saying that everyone needs to blab the reasons for why they feel a certain way to a bunch of strangers on the internet, but let’s at least admit when our reaction is emotional. Let’s change the environment around these sorts of conversations so that we can admit it. Otherwise we’re just Anakin and Obi-Wan talking circles around each other until one of us sets the galaxy on fire.

I find no thrill and no joy in the throne room battle sequence, for purely emotional reasons. And that’s okay. That’s something we can have a conversation about.

…and then the Rise of Skywalker goes on to do exactly what you were worried it would do in that scene. Sigh.

Well… let’s just say that TROS is a lot to process, and I’m more baffled than angered at some of the decisions.