“George, you can type this s[tuff], but you sure can’t say it!”

Harrison Ford

First night at Celebration Chicago, my dad and I plopped on the floor of our hotel room, pizza in hand, and cracked open Master & Apprentice, freshly purchased from the Del Rey booth. Trading off eating and reading at each double-paragraph break, my dad somehow always ended up with the sections filled with Kitonaks, Shawda Ubbs playing Growdi harmoniques, and long strings of Huttese. We finished the first chapter that evening and did not continue this activity the following nights. Partly, we were simply too exhausted by the end of each day’s events, but also – as good a novel as it is – Master & Apprentice was simply not written to be read aloud.

In contrast, when I decided to try reading aloud a single story in George Mann’s Myths & Fables, by the second page, my tone had taken quite the dramatic turn. By page three I was up out of my chair, pacing the apartment. Page five had me gesticulating with my free hand like a bard with an audience gathered about a tavern’s hearth.

Now this is a book tailor-made to be read aloud, beside a fireplace or at the foot of a bed.

Spoilers and Direct Quotes Ahead

Contrasts and comparisons are what you’ll find in this review of Myth & Fables, because the very structure of the book asks for it. The very title encourages us to make connections to collections of fairy tales, legends, and of course, myths and fables. The interconnectivity of “The Wanderer” and “The Dark Wraith” reminded me of how heroes from one story in a culture’s mythology will occasionally cameo in another story.

For the book as a whole, I was personally reminded of The Book of Virtues by William Bennett, which my family read from when I was young. Bennett gathered stories of all types, folklore, pieces of religious texts, Greek myths, etc. all sorted under the various virtues they espoused such as “courage”, “loyalty”, or “responsibility”.

Most of the stories in Myths & Fables could easily be sorted into one of those sections as either the triumph of a virtue or a caution against a vice. “The Knight & The Dragon” is a tale of compassion, for example, while “Vengeful Waves” and its cautions against greed would fit well among the stories of self-discipline. “The Black Spire” is about courage, wrapped up in multiple trappings of other fairy tales.

By the use of misdirection and simple items, the young heroine of “The Black Spire” invokes stories like “The Brave Little Tailor” in which common people achieve great feats by clever means, causing people to mistake the commoner for a grand soldier. That the heroine is forced to rely on simple items follows another trend that is found in fairy tales. Each of her sisters before her takes up weapons from their father – a sickle, a blaster – only to fail. The heroine is then left with a sharpened stick and a petrified piece of a tree to find victory where they failed. Though their plights are in wildly different contexts, this is similar to the youngest son in “Puss in Boots”, who was left with nothing of note from his father’s inheritance, and yet ends up the richest of the brothers. And that element of “the youngest” is another common trapping of fairy tales, which has been previously explored in Star Wars with Queen Trios of the Darth Vader comics.

Another common theme in fairy tales (one that did not become a section in The Book of Virtues) is obedience, and that too is found in four stories of Myths & Fables. In “Black Spire”, disobedience against a loving authority is the inciting incident, the damage of which the heroine undoes. “Gaze of Stone” is a cautionary tale of disobedience combined with arrogance, where both the authority and the rebel are wicked. “The Dark Wraith” feels the most like overt Imperial propaganda, striking fear into the hearts of those who would disobey their parents, their schoolteachers, or the governing body.

In each of the three instances of disobedience in “The Dark Wraith”, the victim of this boogeyman version of Vader is the cause of their own death. They had it coming. They were selfish. They thought the rules didn’t apply to them. And so “The Dark Wraith” came and killed them. The first two victims are merely children, leaning hard into the boogeyman feel, and it’s clear that they are supposed to represent the reason that someone might join the Rebellion. Or at least the Empire’s version of those reasons. The third victim is an outright criminal, allowing the story to paint the Empire as some form of protector. Keep in line, “The Dark Wraith” says. Be good and obey, and the Empire will protect you.

The fourth tale in which we see this theme displays disobedience not as a vice, but as a virtue. In this, “The Droid With A Heart” finds kin in Guillermo del Toro’s fairy tale Pan’s Labyrinth. The tactical droid that defies General Grievous is a hero because it disobeys. Even if – like Ofelia, del Toro’s protagonist – the tactical droid dies for it, its pieces are scattered and passed down among the droid army to keep its story alive.

“It is said… that [Ofelia] left small traces of her time on earth, visible to those who know where to look.”

While the distribution of the droid parts is meant to inspire hope, it also felt a little unsettling. “The Droid With A Heart” is surprisingly gruesome. Without the visual differentiation between droid and organic bodies, the constant description of Grievous’s violence against his own army is something that took me aback. Like The Book of Virtues or a collection of fairy tales, I always envisioned children as the target audience for Myths & Fables, and I could well imagine some of descriptions in these tales scaring a child as their parents read at their bedsides:

“The villagers took to hiding their young in pits beneath the shifting sands, but the dragon was wise and had seen such tricks before. It dug up the children like wriggling worms, one to feast upon each night.”

This is in contrast to another book that Lucasfilm released for children, this one also designed for parents to read aloud. 5-Minute Star Wars Stories is a selection of scenes from the Skywalker Saga films. Mostly unoffensive stories, watered down to carry as little bite as possible. Even the rathtar chase from The Force Awakens carried little in the way of threats, though I did get to teach my nephew the word “Kanjiklub”, so it wasn’t wholly a loss. Now the 5-Minute Star Wars Stories aren’t to be utterly dismissed; artistry both of words and illustrations was put into this book, and they are probably a good starting place for the very young. But it was a good frame of reference to help pull me out of my mild moral panic about scaring children with Myths & Fables.

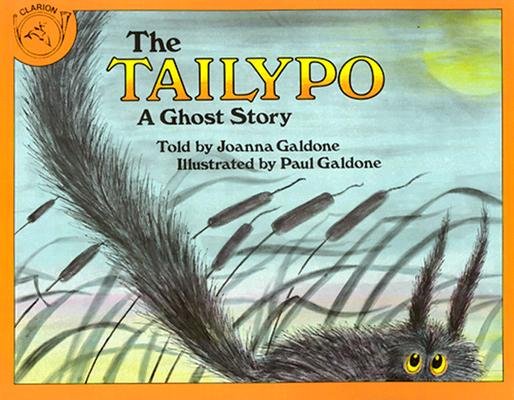

Even some of our most beloved fairy tales have very gruesome origins, and not all have been sanitized by Disney or their competitors over the years. Even if they were, the original stories – or as original as some can get – are often still accessible and marketed to children in bookstores. These moments of intensity can make a story more memorable, staying with children through to adulthood. Two staples of my childhood were the American folktale “Tailypo” (body horror warning at the link) and the retelling of an Ojibwe legend The Windigo’s Return. Both feature an ending similar to “Gaze of Stone” and “The Dark Wraith”: the monster is still out there.

Granted, that type of ending that had some of my peers quitting the Goosebumps series very quickly, but that’s the main reason I see value in Myths & Fables as a bedtime read. There is value in a child learning to overcome fear through the relative safety of a story. With their parent right at their side, walking the child through the most gruesome parts, or even with a child revisiting the tale over and over again by themselves, this is a place for them to learn how to be brave.

If, at nearly thirty years old, I willed myself to watch the Rodents of Unusual Size in The Princess Bride, no one would call it the epitome of bravery. But for a child who had spent nights buried under blankets, thinking giant rats were lurking under her bed, it was a major decision to face fear. Facing that fear had no real danger, which emboldened the child for the next time she was to be brave, and then for the time after that.

Myths & Fables ends with the story “Chasing Ghosts” which I’ve come to regard as the perfect ending for this book, especially as it follows three of the grimmest tales. For even if Ry, the pirates, and Kup’bree’ak all earned their fates, there is still an unsettling finality of either death or a cursed existence. In contrast, “Chasing Ghosts” is a tale about the scoundrel Misook who gets away with everything.

It’s the most light-hearted of the collection, everything playing with a nod and a wink, bringing the reader into the joke. Misook weaves his way out of danger and to freedom, regardless of whether or not he “earned” it, saving any young readers their own degree of moral panic. And the joke the young readers – or bedtime listeners – are in on?

“Only Misook, sitting somewhere with his feet up in a cantina, laughing, knows the truth:” the story was never really true at all.

Darth Caldoth, the Dark Wraith, Krayt, the droid with a heart, all the monsters found in these pages… the child can sit somewhere with their feet up and laugh, knowing the truth. They never really existed at all.

As another salute to the darker side of these tales, the moment I knew I wanted to write a review of Myths & Fables was a single, haunting description in “The Witch & the Wookie”:

“Shadows seemed to leer at them from amongst the trees, describing monstrous things in the darkness.”

A common piece of writing advice I’ve seen is that prose should not draw attention to itself. Like all writing advice, this is up for fierce debate, but I think even if it’s true, there’s a certain pass given to stories that are meant to be spoken aloud. There’s a level of performance suddenly expected on the part of the narrator, even if it’s just George Mann’s prose etched across the page.

We’re supposed to be set reeling from a turn of phrase. We’re supposed to lean in as our storyteller whispers to us an “as you know”, even if we do not know but are delightfully made co-conspirators anyway. We’re supposed to hang on every word, until the hearth’s fire sinks to coals and sleep overcomes us, tales of compassionate knights, fearsome wraiths, clever witches, and brave little girls following us into our dreams.