One of the cleverest, most self-referential character arcs in the original Star Wars trilogy is C-3PO’s ability as a storyteller. In the first movie he claims to be “not very good at telling stories,” but in the final film he recounts the heroes’ adventures to the Ewok village with a delightful blend of humanlike charisma and droidlike sound effects. Either modesty or a lack of confidence was holding our anxious droid back, and as masks fall, it turns out that Threepio can make stories interesting (to everyone except Han, anyway). Vader is actually Anakin; lightsabers are actually useless; and Threepio is actually very good at telling stories.

But what if he isn’t?

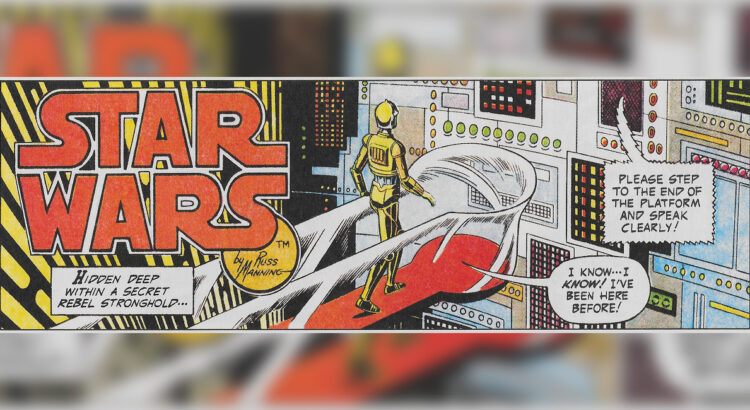

Mistress Mnemos is a room-size supercomputer whose mission is to store all the Rebel Alliance’s data, whether entertaining or not. She debuted in Russ Manning’s newspaper comic strips in 1979, and has never even been referenced since. This in spite of her incredible potential as comic relief, femme and non-humanoid droid representation, and commentary on the nature of storytelling itself. As she is built into the walls of a secret Rebel stronghold and literally plugged into the story’s narrator, Mnemos is the platonic ideal of a captive audience.

As brilliant as she was back then, I think Mnemos could serve an even more important role now. She protests Threepio’s excessive, self-centered tangents — “My banks are overflowing with trivia as it is!” — and that was in 1979, decades before “Star Wars trivia” was the subject of board games, parties, and masters’ theses.

Even her name has aged in a fantastically relevant way: the prefix “mnemo-” means “memory,” one of the most vital themes for a franchise so rooted in nostalgia, so backwards- and inwards-looking, with even its freshest new stories haunted (and frequently visited) by the ghosts of the Expanded Universe. Every spinoff of the original trilogy must contend with its audience’s presumed memories, and that presumption often bleeds into the stories’ themes and the struggles of their characters: Revan’s amnesia, Anakin’s dreams, Yoda’s burnt library. As the audience, we remember the story, while the characters can forget, or try to stop it, or need to move on. But Mnemos must remember, too, no matter how unhappy it makes her.

For a franchise so aware of itself as a story, with its trope-based narratives and operatic reliance on music, Star Wars actually depicts remarkably little storytelling. How did Rey hear the legends of Luke Skywalker? A simple way to integrate the magical, intimate act of storytelling into future projects would be to use it in framing devices. Who better than Threepio to tell, and who better than Mnemos to listen?

Mistress Mnemos spoke her last before The Empire Strikes Back had even been released, but my other favorite storytelling framing devices in Star Wars comics are far more recent: Tales from Wild Space, backup stories in the 2017-20 Star Wars Adventures children’s series, and Tales from Vader’s Castle, published throughout the Octobers of 2018 and ‘19. Both series are narrated by a member of the adventurous Graf family — Emil and Lina — to their misfit crews, generally for the purpose of teaching a moral lesson. Though I love the characters and situations they get themselves into, the “lessons” aspect of their stories isn’t especially compelling. You don’t really need a fervor for morality to want to hear a Star Wars story.

Which is why Mnemos is so interesting to me as a character; she isn’t here for fun, she’s here for work! And she hates it! There is something so valuable about hearing the story alongside an unhappy character (just think of the framing device in another paragon of eighties nostalgia, The Princess Bride). Not only is it funny and ironic, but it gives the story opportunities to anticipate and have fun with the audience’s criticisms. What better way to immediately induce sympathy for a character than to stick them in the exact same position as the audience: forced to listen to this ridiculous stuff?

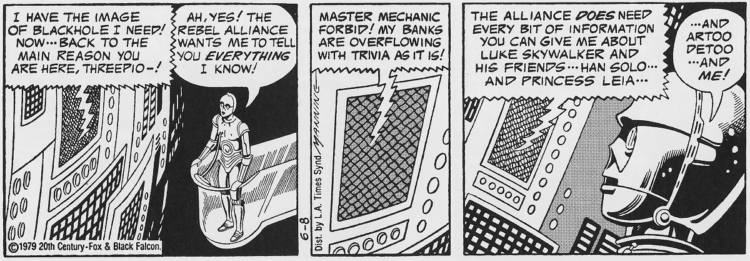

To the right is my favorite panel of Mistress Mnemos. With this line, she not only reveals her own vulnerability, but Threepio’s as well. She patronizes him, just as he would normally patronize Artoo. She is extremely aware of her own robotic function and outraged at Threepio’s apparent disregard of his. But I think the lady doth protest too much — she seems more than capable of judgment herself!

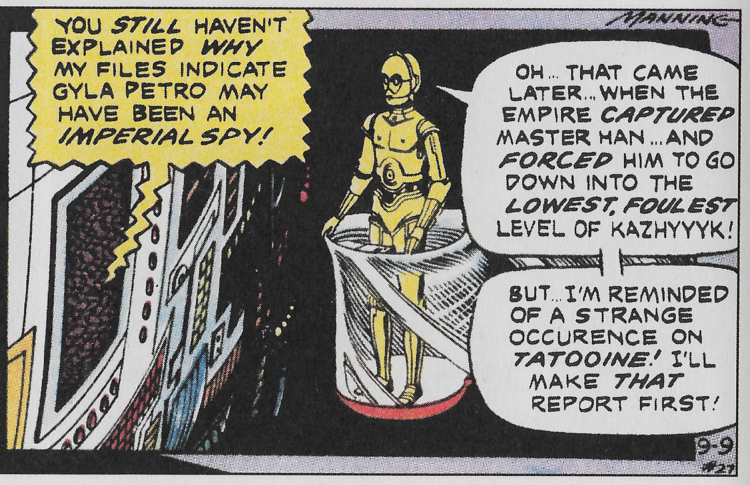

I believe the reason she denies herself moral reasoning is a deep-seated frustration and despair at her own circumstances. After all, she was designed by mobile, sensory people, with mobile, sensory values — but she has neither mobility nor senses herself. Few characters are so nightmarishly trapped in their own bodies; and by extension, their own stories.

The tension between these two is just begging to be resolved. Their relationship could be adapted as the throughline for an anthology series, or a parallel narrative to a long-running adventure story. Either way, it would be an excellent way to re-introduce a forgotten character, show another side of a classic one, and allow the franchise to grapple with the difficult themes of franchise fatigue and the inaccessibility of too much lore.

But perhaps the most important reason why Mnemos, and at least one other Russ Manning character, ought to come back is to finally get closure on this incredible plot hole:

To explain why this plot hole means so much to me, I have to tell the sad story of the end of Russ Manning’s career. For a whole bunch of reasons — his lavish pacing, his unfettered creativity, his numerous excellent female characters, his appealing characterizations for Leia and Threepio especially — Manning is my favorite Star Wars storyteller. For the first three storylines, Manning wrote his own stories with an inspirational degree of creative freedom, especially for the restrictive and stressful medium of newspaper comics:

“The way that I much prefer to write, and this [eventually drove] the Star Wars people up the wall…is to sit down and conceptualize a story. I decide what the main conflict is, who the villain is and what he is, how it ends, how the hero solves it, who the main characters are through the story, and that’s it. I don’t write it out, pre-plot it, or anything of that nature. I didn’t even break it down into eight weeks or twelve weeks…but would just start writing, thinking it would be fresher and more fun for me, every week, to do what was necessary for that Sunday page or that particular set of six dailies.”[1]All of Russ Manning’s Star Wars comics were published in Star Wars: Classic Newspaper Comics, Volume 1 by IDW Publishing in 2017. The three he wrote himself are called “Gambler’s World”, … Continue reading

As one might expect, this freedom was unsustainable:

“The Star Wars people were so incredibly product-conscious, they were so careful with their product, that they wanted to see a synopsis of the story, and when I had that done [I was asked] if I could turn in a complete shooting script so they could look at every single word, deciding whether that word belonged there or not. [They would then] want me to follow exactly what I had written in the script because they had approved it… I could never get to that point once where I could get that far ahead and get that much work done.”

So at the end of the third storyline, Manning was replaced as writer:

“Carol [Titelman] was very kind to me. She let me go for a full year [scripting the strip my way]. But at the end of the year she said, ‘It isn’t working. We don’t have enough control.’ I said I can’t write the other way because I don’t have time, I don’t like to write the other way, and I have no objection if you find a writer that you like, so they got some other writers.”

The panel above shows the entirety of that transition: Mnemos asks for clarification on the loyalties of Gyla Petro, Threepio hints at a jungle adventure, then cuts himself off to talk about a completely different adventure, with a completely different writer.

Manning continued to draw for the comic until June 1980, when declining health forced him to retire; he died a year later, at only fifty-two.

Manning was the only writer who ever wrote Mnemos, or Gyla, or Sharlee, or Gamine, or the President of Vorzyd V (though his male character Blackhole was developed by other writers). Another story set on Kashyyyk would have played to Manning’s strengths; after all, he spent twelve years drawing Tarzan comics.

Despite what he made Mnemos say, Russ Manning was very good at telling stories. His style was more slow-paced and meandering, but he used that space to have fun with the setting and deepen his characters’ relationships, especially that between the droids. Much like his version of Threepio, who addresses Mnemos without a hint of anxiety or modesty, Manning set his own boundaries and timeline based on what he could do and what he wanted to do. This freedom is apparent in his confident work. We can’t know what he was planning for Gyla Petro’s backstory, but we can take inspiration from his unique voice and honor his legacy to finally answer Mnemos’ question, and finish Threepio’s story.

I’ve written more about Mistress Mnemos and Russ Manning on my blog “Daily Star Wars Comic Panel”.

| ↑1 | All of Russ Manning’s Star Wars comics were published in Star Wars: Classic Newspaper Comics, Volume 1 by IDW Publishing in 2017. The three he wrote himself are called “Gambler’s World”, “The Constancia Affair”, and “The Kashyyyk Depths.” I found his quotations in the introduction essay, “From the Databanks of Mistress Mnemos: Remembering Russ Manning” by Henry G. Franke III. |

|---|