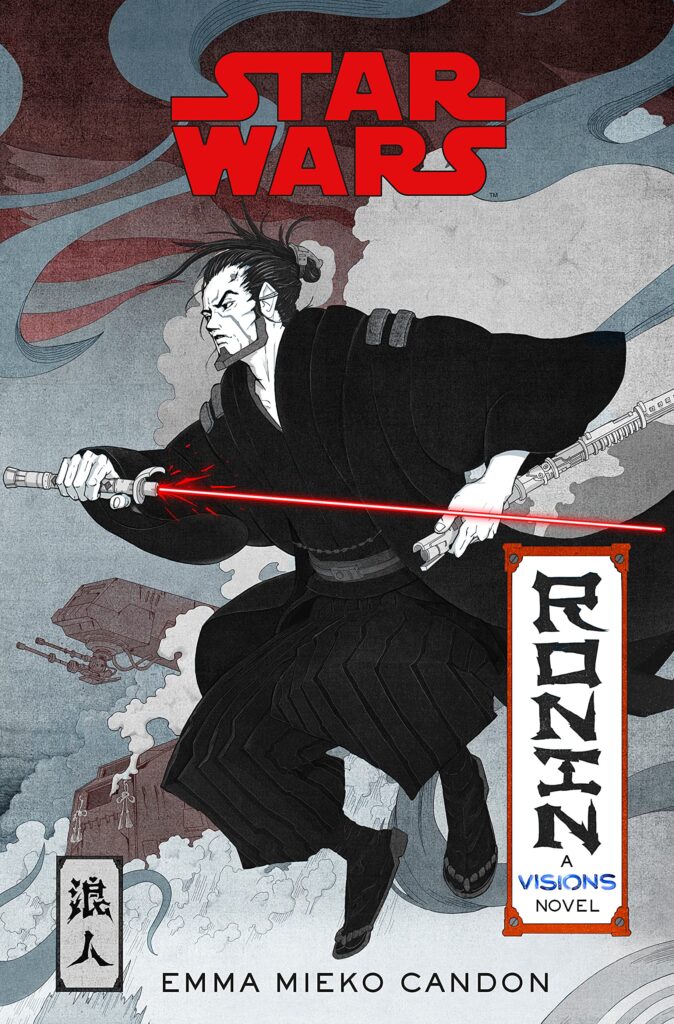

Emma Mieko Candon’s novel, Star Wars Visions: Ronin, is remarkable in several ways. It’s remarkable for taking the story hinted at in the Visions short “The Duel” and turning it into a full narrative, it’s remarkable for generating its own setting unmoored (or better yet, unburdened) by existing Star Wars storytelling and continuity, it’s remarkable for LGBTQIA+ representation (thankfully something SW publishing seems to be pretty good about), and it’s remarkable for putting Star Wars squarely in a Japanese-inspired milieu and still feeling perfectly like Star Wars. As Candon put it in their author’s note, Ronin is an “iterat[ion] on an American saga that is itself an iteration on Japanese narratives.” Like the Star Wars Visions shorts themselves, it feels like Star Wars has come home to where it all began.

A lot of ink has been spilled on the influences of Star Wars, from Flash Gordon adventure serials, to the monomyth, to political commentary on Nixonian America. By now most of us know of the historical allegories about Nazi Germany, the Vietnam War, the American Revolution, and the Roman Republic’s transformation into the Roman Empire. Many of us also know that George Lucas took inspiration from Japanese, Indian, and Chinese cultures for ideas of the Jedi and the Force — and SW’s cultural influences (or depending on how you see it, appropriations) go even beyond that when we consider costuming, location design, and the ever-expanding on-screen world of Star Wars on cinema and television. You could probably write a whole book on the real-world cultural influences from the Americas, Europe, Africa, Oceania, and Asia on Star Wars.

Star Wars has many roots. But those aren’t the only place Star Wars belongs. It also belongs to everyone who’s engaged with it, who’s thought about it — but for so long, Star Wars had this idea that it had to look, and feel, a certain way. Star Wars Visions broke that idea for the screen just as Ronin broke it for the page. And I think that’s great.

Star Wars publishing has shown a willingness to experiment with books like From a Certain Point of View from Del Rey or The Legends of Luke Skywalker from Disney-LFL Press. They’ve hired an author pool of different backgrounds and experiences, and I’d love to see that continue going forward. I’d also love to see authors able to take their experiences and tell stories that we might not have previously thought really fit in Star Wars, but actually do. Ronin shows the way — if we can have space dreadnoughts with pavilions, gardens, and sliding wood-and-paper doors, we can have it all. We can frame our Star Wars stories in ways we never thought possible. But we can do it in an honest way, that doesn’t look like we’re pillaging from different cultures to lend our stories exotic flavor — by letting creatives engage with Star Wars in a way that’s informed by their own backgrounds and experiences.

Why Ronin is So Breathtaking

The thing about Ronin — like the Star Wars Visions project as a whole — is that the Japanese cultural framework enhances, rather than takes away from, the “Star Wars feeling” in each of the stories. It’s important that we got nine shorts and one novel, because no single story could ever truly take on the burden of being an entire culture’s “take” on Star Wars. Instead, we’ve gotten ten takes from ten creative teams (I’m counting Ronin separately from “The Duel”) showcasing that there’s no such thing as a monolithic “Japanese take on Star Wars” and that each creator tells a unique story influenced by their background and experiences.

The galaxy of Emma Candon’s Ronin feels different from the canonical Star Wars galaxy that we know (though it doesn’t necessarily have to be), and the important part is not that it’s different but how those differences function within Star Wars storytelling. Think of Candon’s galaxy as a mirror to the galaxy we know — mirrors play an important role in the story, and even at the meta level the reflection of familiar Star Wars themes into a different context teaches us something.

The Jedi are a great example — in Candon’s telling, the Jedi are closer to historical samurai — they have clans, they wield political power like feudal daimyo (lords), and they serve an empire. At first blush this seems very different from the Star Wars we know — but is it? Compare these Jedi to the Jedi of the prequel trilogy: similarly dogmatic and set in their ways, seemingly tied at the hip to a governmental bureaucracy, and functioning as generals during the Clone War. The differences are instructive: Ronin’s Jedi relish war and see it as an opportunity for glory, while war is the downfall of our filmic Jedi. In the announcement interview for the book, Candon explained that they set up the Jedi this way to parallel the socio-political role of samurai in the jidaigeki films, which are suspicious of the samurai as a class.

Viewing the Jedi through this alternate framework becomes a way to view and get a better understanding of Star Wars as we know it. The samurai-inspired Jedi mirror our canon Jedi just as the Empire’s own failings reflect the political and economic failings of the various republics we know in Star Wars. Viewing these through a different lens allows us to wrestle with ideas that we might not get to see more directly. It turns out the Japanese framework not only serves as a way to explore Japanese cultural and historical narratives, but Star Wars ones as well.

The story of Ronin is nothing without its characters — and they’re part of this interpretive framework too. Each of them has a different background and relationship to the galaxy Candon created. The titular Ronin has his own history with the Jedi and Sith as do each of the characters he meets. The bandit Kouru has her past and is more than just a villain, while the Traveler and Chie are both deeply ambiguous and very interesting. The pilot Ekiya is the most interesting member of the main cast to me, precisely because she lives outside of the Jedi/Sith/mythic framework and can expose the dogma of these “space wizards” to critique precisely because she’s not buried inside them. Narratively Ekiya mirrors the story of Ronin itself: looking at the themes of Star Wars from the outside and allowing the audience to look at them critically. Does the all-important Jedi-vs.-Sith conflict make all that much sense given the impacts it has on the average person, or does it obscure what should actually matter to the characters in the setting? It’s ample food for thought.

Models to Follow

I think Ronin really struck me in a way that Star Wars novels haven’t in quite a while, precisely because it was able to feel so different and so familiar in many ways. But it wasn’t only the meta story — it was a deeply engrossing story itself where all the cultural trappings actually felt familiar and right for Star Wars, as if they’d been there all along. And that brings me to my next thought: could this happen again? Could we get more of this?

As I mentioned earlier, Star Wars has taken a lot of inspiration from real-world cultures in the realm of costuming, design, and story elements. At the same time, it’s a quintessentially twentieth-century-American story at its root – and as the story expands it continues to reflect its original genesis. There’s room for Star Wars to pay its respects to the places and people whose stories it adapted to create its modern mythology though — he question is how to do this right? Star Wars would need to both stay true to itself, and at the same time be respectful of the cultures that it would be including to try and avoid the persistent threat of stereotyping or appropriation.

The “easy” answer (nothing about this is easy) is to invite more creatives to tell the stories in their own voices, much like the Star Wars Visions project did. I’m thinking specifically of the Disney-Hyperion imprint Rick Riordan Presents. Riordan created the Percy Jackson series and several others, successfully adapting Greek, Roman, Norse, and Egyptian mythologies to modern stories for young people. When audiences clamored for him to tackle more mythologies, Riordan came to the realization that he perhaps wasn’t the right person to tell these stories and instead used his great success to elevate other writers who could explore their own cultural mythologies through the platform of the Rick Riordan Presents imprint.

Star Wars publishing would be greatly enriched by such an approach: it would allow other authors of different backgrounds to engage with Star Wars through their own framework, giving us potentially amazing stories in ways we hadn’t thought possible. Star Wars has already pulled inspiration from all over the world — I find it difficult to imagine that people would write stories that didn’t feel like Star Wars. And if a story ended up feeling significantly different, that’s a feature, not a bug. Star Wars is big enough that it can take on a few different types of stories: if it can handle a LEGO Holiday Special, it can handle stories through different cultural lenses as well.

Let’s try a few examples of how these lenses could work. There’s always more mining the vein of the Jedi: since the Force is based on so many cultural traditions, we could have a story about the Jedi Order drawn on South Asian cultural traditions. Ideas about dharma, reincarnation, cycles of life, and the spirituality of rivers and mountains seem ripe for exploration in Force stories (they don’t even have to be Jedi — I’m always a fan of showing the exploration of the Force through non-Jedi or non-Sith mindsets). I’d also love to see a story set on Naboo that explores that world through a South Asian lens since many Naboo names like Padmé, Pooja, Sheev, etc. are Indian in origin — it’s possible George Lucas just liked the sound of those names (like Ashoka or Akbar becoming Ahsoka and Ackbar respectively), but we can do something with that too: explore Naboo’s connection with nature, explore the high esteem of artists and poets in their society, or even use some of the more fraught social/colonial history of the different countries and peoples of South Asia to talk about the Naboo people’s poor relationship with the Gungan people and their attempts to right those wrongs. Or perhaps we could have a story about a conqueror or emperor that isn’t based on only the British, the Romans, or the Germans — why not the Mughals? I’m proposing stories from South Asian contexts because that’s my background so I feel less awkward talking about it than I would talking about someone else’s culture, but Star Wars has taken influences from cultures on every continent. The important thing here is that we wouldn’t be reframing or changing Star Wars as we know it. Instead, I think we would be taking what we already know about Star Wars — an existing connection or influence — and exploring it through real-world cultural ideas in order to tell us something new about Star Wars.

I think Star Wars has such narrative strength not just because it taps into different storytelling traditions (the hero’s journey, pulp sci-fi, etc.) but because it’s a myth grounded in the familiar. The “used future” of Star Wars has echoes of reality — Tatooine (Tunisia), Naboo (Italy), Yavin (Guatemala), and Jedha (Space Jerusalem, via Jordan) were all filmed at or inspired by real places and even the war-fighting is drawn from cultural memories of World War II. Human history is so compelling and interesting and helps our fantasies feel real in a way that wholly invented stuff doesn’t — there’s a reason that modern epics like Star Wars, Dune, and Lord of the Rings all draw from the real world for their imagined worlds. But just picking and choosing from real places for flavor isn’t good enough — authenticity can add more. Most importantly — such an approach honors Star Wars as the modern mythology it is, allowing people to engage, respond, and add to it in dynamic ways. Do the stories need to be canon? No — but arguably the focus on canon can be pretty inhibiting anyway; a story doesn’t need to be canon to be good.

This Isn’t the Only Answer

I think continued Star Wars storytelling in the vein of Visions and Ronin, whether or not it follows the concept of Rick Riordan Presents, is a great way forward to keep Star Wars dynamic, to honor Star Wars’ creative origins and to reflect its nature as a modern mythology. Before anyone gets the wrong idea, I’m not saying that such stories should replace traditional Star Wars stories or that they should be the only way forward — I’m just saying that it’s something I’d like to see, in addition to everything else that Star Wars has cooking.

Traditional Star Wars storytelling will probably always still be the main line of the franchise — and the canon will probably continue to be the main avenue of future adventures. I’m not saying that needs to change in order for Star Wars to respect its sources. I think I’d like to see more voices tell stories within the Star Wars canon too — I don’t want to relegate these stories to purely alternative cultural takes on Star Wars, especially given how much Star Wars has already pulled from world cultures. But figuring out how to deal with this inside of canon is a much trickier question. And am I really saying that you can’t pull from a real-world cultural source if it’s not your own culture, and any attempt to do so is appropriation? I don’t think so — I think storytelling would be creatively impoverished that way.

These things aren’t easy — I think at the end of the day if people are respectful and tell stories in good faith, that means a lot. Allowing more voices at the table and more stories to be told will only enrich Star Wars storytelling and is a great first step as we figure out the rest of this stuff. At the end of the day — we want good stories, told respectfully and told well — and if we get those, we’ll be better for it.

Star Wars has always suffered from the era of it’s creation. Before the internet and before the travel shows, the world seemed so much bigger that an American director wasn’t worried if he named a planet after an obscure desert area of Tunisia, or used a real world language for an alien race spoken by very few people. The world is much smaller now and going forward they really should, and I think have to an extent, move away from referencing Earth cultures and places. It always takes me out of any narrative when they write stories in that way.