I have been stunned when individual males would confess to sharing intense feelings with a male buddy, only to have that buddy either interrupt to silence the sharing, offer no response, or distance himself.

The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love by bell hooks

I have begun reading bell hooks’ The Will to Change as a means to better understand my own masculinity. The feminist author was one of several voices I tuned into to help me navigate the imposter syndrome I had regarding my gender, and as I was making my way through one of the chapters, my mind kept circling back to The High Republic Adventures.

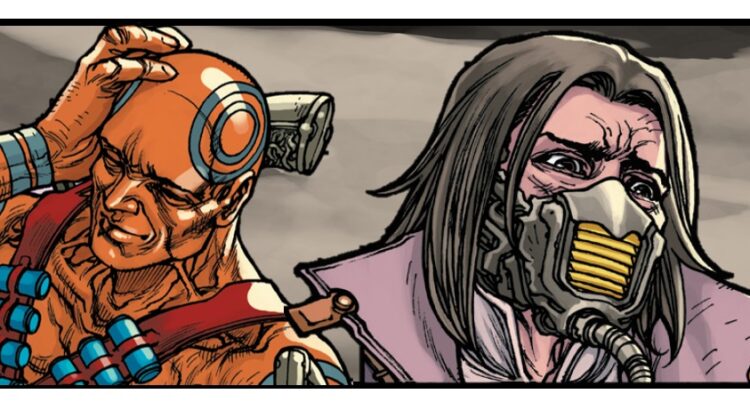

The preview of issue #5 of the comic had been released two days prior on May 4th. I was of course obsessed with a certain queer coding from Dexter Jettster, but that wasn’t the primary reason why the preview kept repeating in my head. It was the fact that he was saying these things to Alak, another man.

The Will to Change is a feminist examination of patriarchy’s violence against men. In this book, she speaks a great deal about how our society keeps men trapped in a loop. It is good and healthy for men to reject patriarchy, to redefine masculinity apart from it. But then our society, including women – steeped as we all are in patriarchal norms – rejects the men who attempt to break free, for not being “manly enough”. In particular, men are shamed for showing “weakness” or emotional needs. They are expected to maintain emotional isolation from others.

This is also known as toxic masculinity, a term which actually came initially from men. Essayist F.D. Signifier points out that it began as a way to describe “all these things that we (men) do in the name of performing masculinity that low key suck and hurt us in the long run. (…) self-denial, like limiting emotional range, like stoicism and wanting to be a lone wolf, and not wanting to ask for help.”

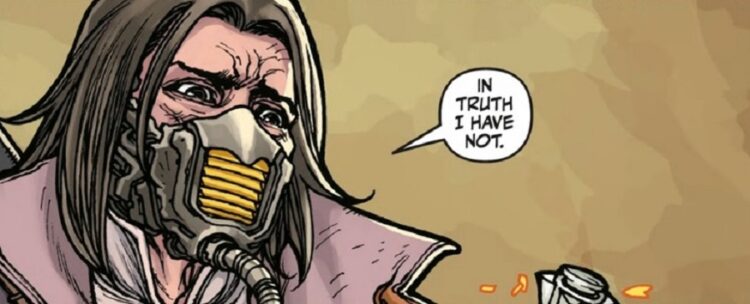

What The High Republic Adventures #5 gives us is two men being vulnerable with each other as they discuss what it’s like to be in romantic or queerplatonic relationships. Dex is free to express the joy and fullness that he feels. Alak is free to express his own concern and uncertainty. Alak seeks emotional openness from Dex, and when Dex gives it, Alak feels free to be emotionally open as well.

This is an arc that Alak has been on throughout this run of The High Republic Adventures. Every issue has given Sav and us readers a glimpse further into Alak’s relationship with the pirate hunter Raf Thatchburn, revealing that he’s not as stoic as he first appears.

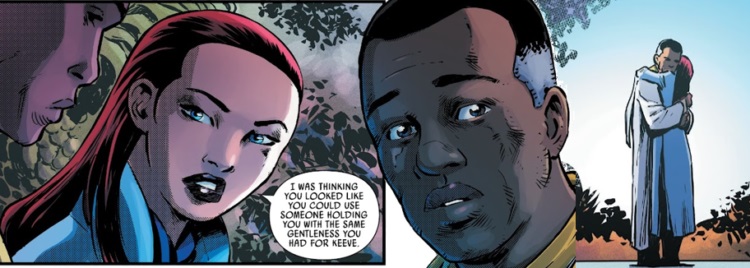

In issue #2, Coromont knows Alak well enough to understand that Alak’s surliness is a sign of other emotions like uncertainty and concern. In issue #3 Alak trusted the entire crew enough to have them around as a support system during personal conversations with his boyfriend. And in issue #5, Alak is able to trust both Dex with his own emotional vulnerability and Shan to metaphorically and physically protect that space for him.

I think it’s also important that we are specifically seeing a man of color receive this support from his community. White men are often afforded more leniency in their expressions of masculinity, because in our culture, white is the default. Any man who is not cis, heterosexual, straight-sized, able-bodied, or white is expected to perform masculinity twice as hard for less acceptance.

A Black man being treated with gentleness was an equally rare and beautiful moment in Daniel José Older’s other High Republic comic – Trail of Shadows – and it’s again beautiful to see as an ongoing theme for Alak, a gay, disabled man of color, here in Phase II.

I’m not the only reader to have noticed the importance of this moment. Wes of Queers Watch noted this exchange, and Ryan of Mynock Manor said in his review,

Dexter Jettster, Alak, Quiet Shan, Therm Scissorpunch, and Coromont might be in the middle of a warzone, but they are having casual conversations while punching their way through the city, actions befitting of their legendary status. It might seem like an 80’s action movie this way, but their conversations are the inverse of what you’d expect as it’s tender, open, and honest subjects instead, not false bravado and toxic masculinity which push outdated ideals on what men should be like.

As Ryan points out, this comic has more than just Alak and Dex’s conversation. Thermoculus Krisintvolt Scissorpunch also has something to get off his chest. It begins with Coromont asking him what’s wrong, and in response, Therm admits that he is scared and doubtful of himself.

Setting aside Rado’s declaration that he’s still planning to arrest all of the pirates someday (which is why we say No Cops at Pride, thank you), we get to see another moment in which a man chooses to be vulnerable with the other men in his life, and the others are there to catch him. Through that support, through a positive response to his fear, Therm is able to step up to the next challenge that comes his way.

These are wonderful character moments in general. However, as I have mentioned previously, it is also important to take into account the primary audience of this story. This is a comic for children.

In The Will to Change, bell hooks pointed out that “[t]here is no body of feminist children’s literature that can serve as an alternative to patriarchal perspectives, which abound in the world of children’s books.” A child can be raised in the most anti-patriarchal family, but media surrounding him will still insist that he follow certain roles. And for a child raised in a toxic masculine environment, he will have little to no examples of what healthy masculinity might look like for him.

Gender stereotypes in literature contribute to self-identity and self-image development in young children. Gender stereotypes are societally constructed and ingrained into children at a young age. Not only do children accept these stereotypes without question, they are also more likely to internalize gender stereotypes because of the emphasis on illustrations and repeated readings.

Nebbia, Christine C., “Gender stereotypes in children’s literature” (2016). Graduate Research Papers. 680.

Filmmaker and essayist Jessie Earl recently released a two-part essay about her experience growing up, about how the expectation of a specific type of masculinity affected not only her as a trans person, but everyone who was raised as a boy. She and others had been told to be alone, to mask their emotions, and sever any connections they might make with others. Earl speaks about how – as a result of this pressure – characters who deliberately isolated themselves with masks and anger ended up resonating with her experiences as a teenager.

Fortunately, the media landscape has been changing since bell hooks published her book in 2004. For one example, the children’s cartoon Steven Universe (2013-2019) dedicated many episodes to tackling toxic expectations of boys, showing the titular hero Steven embracing masculinity in ways that are healthy both for the people around him and for himself. For another example, we have The High Republic Adventures.

Kids reading this comic are going to be able to see five different men showcasing emotional openness with dignity and support. And they will be able to see these tender moments in contrast with Raf Thatchburn, Saya Keem, and Bazrip Ratht Sav Malagán. Interspersed before, after, and between the moments of healthy masculinity are examples of emotional isolation.

As we saw in the last issue, the Dank Graks are a crew in which every member must remain on alert. They cannot trust even each other to care for their emotional needs (except maybe – as we are told – for Drrn, the old softie). As a result, Sav ends up herself falling into the same patterns of the Graks. She locks up her emotions and knocks Saya over in a manner similar to the Graks’ pranks. Even when Saya becomes elated at the fact that Sav saved her life, Sav offers no response and distances herself from the opportunity for emotional closeness.

We of course have very clear reasons for why Sav is acting this way. She’s undercover, it’s self-preservation. Which still manages to reflect why men emotionally isolate. They’re taught to mask their emotions, and it’s a different type of self-preservation. Watching Sav navigate the toxic environment of the Graks only serves to highlight the healthy masculinity in Maz’s crew.

Issue #5 ends on Raf Thatchburn, who has been on a bit of a parallel track to Alak throughout the comic series. Not only are they boyfriends, but while we see evidence of Alak continually seeking and accepting connection from his crew, we see Raf deliberately isolate himself from that same crew.

Even when provided with a chance to connect with the pirates, Raf chooses to perform a role (pirate hunter in actuality, toxic masculinity in metaphor) that separates him. When Maz breaks up his fight with Alak in issue #1, Raf cuts his own explanation off. He chooses to storm away. After he and Dex team up to escape the Graks and protect Sav, Raf undercuts their new common ground by threatening Dex. Raf continually rejects emotional connection for the sake of performing a specific, societal role.

When we first see Raf in issue #5, it is again in contrast to Alak, despite having been asked to come by the pirate. Alak voices concerns about Raf’s well-being. Raf is focused on the events from a very detached perspective, focused on solving whatever crime is at hand. But then in a moment where Sav herself is able to choose vulnerability – giving up her lightsaber to send a message – Raf finds himself responding in kind.

Not only does he show his emotions for the first time, the issue itself ends on the suggestion that Raf may actually seek connection with the same people he’s been rejecting this entire run.

With all these character moments intersecting, issue #5 of The High Republic Adventures acts like a mini showcase of what healthy masculinity could look like. Not just in the sense of a man being a good person, but in the sense of men – collectively – being in vulnerable and supportive community with each other.