In a series named Star Wars, it’s inevitable that war stories will influence the universe. From the beginning, Star Wars has been a universe of war and battles. The films, however, did not go into “war story” mode that frequently. A New Hope focused on the individual adventures of its heroes, only widening its scope to focus on the war being fought between the Rebellion and Empire in the final raid on the Death Star, which drew heavily from the World War II aviation film The Dam Busters for inspiration. The Empire Strikes Back opened with the frenetic ground action on Hoth, but from there became a story of Luke’s Jedi training and Han and Leia’s flight from the Empire. The prequels gave us the opening and closing battles of the Clone Wars, but declined to become simple “war films.”

The films borrowed techniques and tropes from war films when it was time to depict the big battles (the pre-battle briefings, the comms chatter during battle heavy with military-sounding lingo, the visual storytelling used to depict a battle beyond the experience of simply a few lead characters), but they did not exist simply to tell the stories of their wars. They borrowed from, but were not themselves military fiction, a term I like as it suggests slightly more specifically the defining characteristics in which I am interested: fiction that is about the military itself and concerned with military actions.

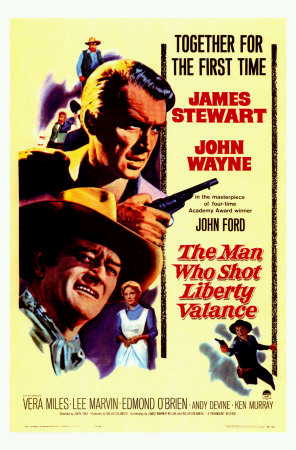

The Expanded Universe has followed that lead. There is usually a war, or at least a battle, and the battles often borrow from military fiction for their telling. Various historical military influences, especially as filtered through fiction, have had their own impact on the nature of the universe — the mixture of Age of Sail and World War-era naval warfare that informs the franchise’s space combat, its World War II dogfighting, large-scale ground combat that owes more to the Civil War and World War II than a realistic consideration of combat tactics in an advanced-technology setting, the medieval clashes between Jedi and Sith in sources like Jedi vs. Sith and Tales of the Jedi. Since that observation is not particularly revelatory, however, that’s not the aspect I want to focus on here.

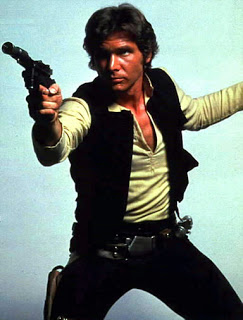

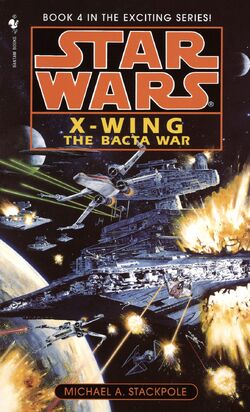

The unique opportunity offered by the greater variety of the Expanded Universe is the chance to do “pure” military fiction, stories that are entirely or significantly about the military, interested in military details, and follow military characters and actions. The X-wing and Republic Commando series are perhaps the most readily notable military science fiction, following protagonists in military units. In the case of the Republic Commando series, the protagonists are clone commandos operating within the military sci-fi “space marine” tradition of grunts in ground combat. Michael Stackpole’s X-wing novels and comics follow the flyboys of Rogue Squadron, while Aaron Allston’s Wraith Squadron X-wing novels blend commando and aviation action.

These are not the only military fiction on display, however. The video game Republic Commando, as well as the X-wing and TIE Fighter video games drew from the same well for interactive Expanded Universe action. The Black Fleet Crisis trilogy prominently followed a fleet, and the politicians and commanders at home, through an entire war. It delved heavily into command structure, military intelligence gathering, and other issues of naval organization that most Star Wars novels skip, and showed a Tom Clancy-like interest in modern military affairs. To the Last Man, an arc of Empire, was directly inspired by the British colonial action of the film Zulu, which dramatized the real-life defense of Rorke’s Drift. The first Clone Wars novel, Shatterpoint, focused on telling a “horrors of war” story influenced by Apocalypse Now.

Yet, when all is considered, the amount of military fiction in the Expanded Universe actually isn’t that heavy, relative to the EU’s size. I think there could be room for a great deal more. We haven’t had a military comic series since X-wing: Rogue Squadron ended in in 1990s, but I think a comic following a military unit could provide an excellent set of ongoing adventures while playing to the popularly known, high-selling elements of Star Wars like X-wing-vs.-TIE action or stormtroopers and Star Destroyers. Fans have clamored for years for more X-wing novels, or a TIE Fighter series following the popular Baron Fel. Military-focused fiction on a larger scale, like The Black Fleet Crisis attempted, could provide an ideal path to telling a more unified story of the Clone Wars — stories about which have tended to focus on single, random battles on single, random planets rather than coherent large-scale campaigns — on a strategic level, and potentially bringing fan-favorite or established but underused characters like Pellaeon and Dodonna into use. The many untold or merely hinted-at campaigns of the New Republic would also be fruitful ground for a military fiction treatment.

There are also entire subtypes of military fiction that have yet to be fully explored. The style of heroic historical military fiction displayed in the Horatio Hornblower, Sharpe, and Aubrey-Maturin novels, which follows a heroic soldier or seaman as he fights in a war or wars and rises through the ranks in a series of adventures, has yet to be fully explored in a Star Wars context. I think it is especially promising as a way of introducing new characters or exploring existing ones. Imagine a comic series following an intrepid young lieutenant in the Old Republic’s Judicial Fleet as he tames the wild Rim and rises through the ranks in a series of naval adventures, or a set of Gar Stazi novels charting the Legacy-era Supreme Commander in his younger days as he climbed the ladder in earlier clashes.

Star Wars cannot devote its storytelling entirely to war stories and the military — massive aspects of the saga would go missing — but considering the importance of war to the saga’s storytelling, it could do much more to tell war stories and develop an aspect of the setting — the soldiers, pilots, admirals, and generals who belong among the cast — that has too often gone neglected in recent years.