In the process of writing about the supporting-character situation of the Expanded Universe, a few thoughts occurred to me about the pernicious effect of prequel-style Jedi characters — specifically, the way that Jedi-from-birth recruitment, and its corresponding tendency to identify Jedi purely as Jedi, limited opportunities to define Jedi as unique characters. Nanci’s excellent article on Tosche Station soon afterward hit that same point as part of a larger critique of the prequelization of the Jedi, so I decided I could let the topic sit briefly before I returned to it. Now, I think, is the time to revisit the topic in depth.

A diverse Jedi Order

Before the prequels established that the Jedi of their time were taken from their families in infancy and trained in seclusion from the galaxy, the Expanded Universe ran with the idea that most Jedi were trained as adults or youths. Furthermore, given Luke’s example as a farmer-turned-freedom-fighter-and-fighter-pilot, the EU did not take the calling to be a Jedi as an exclusive vocation, a full-time occupation for monks dwelling in a Temple away from society.

The result of this was an incredibly diverse Jedi Order. The first Jedi candidates were adults who had escaped identification as Force-sensitive; by necessity this meant that they had already developed identities independent of the Jedi. Corran Horn was a police detective who became a fighter pilot and married a smuggler. Kyle Katarn was a farmboy who signed up to be a stormtrooper, but defected after the Empire killed his father and became a Rebel mercenary and commando. Tionne was an avid historian and musician with an interest in the Jedi. Kam Solusar was an Imperial Dark Jedi redeemed by Luke. Kyp Durron was a child political prisoner put to work as a spice miner. Mara Jade was an Imperial spy and assassin who served the Emperor personally before becoming second-in-command of a smuggling and information-brokering cartel, then a merchant captain. Streen was a hermit who loved birds. Gantoris was a leader of his remote, hardscrabble people. Cray Mingla and Nichos Marr were accomplished scientists and engineers. Dorsk 81 worked a nine-to-five job in a cloning center. Cilghal was an ambassador. Leia was a princess and senator who became a freedom fighter and diplomat, then political leader of the galaxy while raising a family.

These Jedi were a collection of people with different skill sets and life experiences. They had families, friends, and lives outside the Jedi Order. This Jedi Order of spies, commandos, scientists, fighter jocks, cops, businesswomen, diplomats, smugglers, and farmers was bursting not only with background detail, but different competencies that informed the characters’ story roles and the personalities they brought to the table. Rather than being defined by their status as Jedi, they had independent existence that ensured they were fully-formed characters.

This continued even with those generations of Jedi who trained as youths. Because they were not separated from their families before they could walk, individuals were still able to develop outside the Jedi Order and gained unique backgrounds. Jacen, Jaina, and Anakin had famous parents and a set of adventures under their belts before they were even old enough to start attending the Academy. Anakin and Jaina shared an aptitude for mechanics, while Jacen preferred animals and jokes. Jaina was a talented pilot who was friends with Zekk — an orphan scavenger who became a Jedi trainee himself. At the Academy, they met Tenel Ka Djo, an outdoorsy princess; Raynar Thul, slightly pompous heir to a merchant house; Lowbacca, Chewbacca’s nephew with his own immediate family who played into the story; Tahiri, raised by a tribe of Sand People; and Lusa, a former Imperial captive who became ensnared by an extremist group before joining the Jedi.

Furthermore, these rounded characters were not required to act identically. Full-time Jedi weren’t required; Jedi could live on their own and hold down different jobs while being Jedi, just as Luke had been a fighter pilot commanding a squadron in the Rebel military at the same time he had become a Jedi Knight. Leia was a Jedi and the president of the New Republic simultaneously. Kyle Katarn learned to be a Jedi, then returned to fighting the Empire in a commando unit. Jaina Solo joined Rogue Squadron during the Yuuzhan Vong War while still serving as Mara’s apprentice. Cilghal became a senator after graduating from the Jedi Praxeum. Keyan Farlander continued serving in the military, rising to become a general. Corran Horn kept flying with Rogue Squadron until he retired, and rejoined the military during the Yuuzhan Vong War. Kyp Durron put together an independent pirate-hunting squadron. Danni Quee continued her scientific endeavors while training with the Jedi. Some Jedi remained single, while others married and started families. Students and teachers lived at the Jedi Academy, but graduate Jedi Knights roamed the galaxy.

The influence of the prequel Jedi

These Jedi, so diverse in lifestyle, background, and characterization, stand in sharp contrast to the Jedi of the prequel model. By having its Jedi trained from birth inside a rigid Jedi Order, the prequel model eliminates so much of this potential diversity. There are no cop Jedi, no fighter jock Jedi, no scientist Jedi, no politician Jedi, no business Jedi. There are no Jedi with families. No Jedi serving in the Senate, in a fighter squadron, in the laboratory. Jedi may train in a few specialties, but this doesn’t replace the experience of being in one of those roles in a Jedi-independent context, surrounded by Forceless colleagues, defining oneself through a career. Instead, all Jedi have the same monotonous background: Jedi raised inside the Jedi Temple by other Jedi raised inside the Jedi Temple, going on Jedi missions with other Jedi who go on Jedi missions. The option for a character like Saba Sebatyne, whose upbringing within Barabel culture has left her with an incredibly distinctive and unique personality, simply isn’t there.

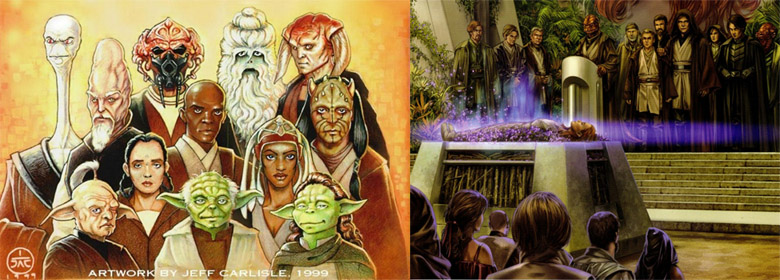

It is not impossible to develop individual characterization in this situation. A sharp writer like John Ostrander can do a great deal to set Jedi characters apart with strong personalities and genuinely unique story roles. But most prequel Jedi, even the better-characterized ones, are not quite as distinctive as Ostrander’s. Qui-Gon is distinct from Obi-Wan in outlook and attitude — but he is not nearly as different as he could be. Given twelve Jedi at once in the form of the Jedi Council, creators did an admirable job of trying to develop some sense of distinction in personality and specialization — but they couldn’t escape the fact that they are stuck doing variations on the same basic template. You could switch out Eeth Koth, Saesee Tiin, Kit Fisto, Ki-Adi-Mundi, and Adi Gallia in most stories and not notice any difference at all. The restrictions on storytelling potential are real and significantly limiting.

The prequel Jedi Council of twelve prequel Jedi — one of whom is a little more aggressive than the others, one of whom hasn’t taken an apprentice and is a great pilot, one of whom knows Chancellor Valorum, etc. — is a significant change from the Jedi Council of the New Jedi Order — a married couple consisting of a sweet-natured farmboy fighter pilot and a harsh-but-loving reformed assassin/spy/smuggler, a hard-bitten veteran commando with a history of struggling with the dark side, an intensely practical detective/Starfighter Command colonel married to a smuggler, a reformed Dark Jedi and his musician wife, a bachelor ex-slave miner who committed genocide in a vendetta over his family, a gentle healer with a political background, etc. Mike Cooper will point out that the prequel Council is much more visually diverse, but it is the New Jedi Order Council that is vastly more diverse in character.

This distinction is especially clear in the creation of brand-new Jedi protagonists. Jedi created outside the prequel context during the New Jedi Order still had distinctive characteristics. Kenth Hamner was an ex-fighter pilot and current military liaison, which informed his by-the-book, law-and-order personality and his administrative, diplomatic, and leadership expertise. Saba Sebatyne was raised in Barabel culture, giving her a distinctly alien personality and the mindset of a hunter. Wurth Skidder had no particularly unique background, but was infused with a headstrong, cocky personality and a particular agenda to take the fight to the enemy. Ganner Rhysode was an arrogant, narcissistic Jedi who saw himself as a naturally superior hero before he got his ego under control.

Post-NJO, when the prequelization of the Jedi took hold? Quick, tell me the difference between Valin Horn, Jysella Horn, Natua Wan, Kolir Hu’lya, Seff Hellin, Doran Tainer, and Thann Mithric? If you answered, “I don’t know,” you’re correct! All are born Jedi who have never done anything other than hang around the Temple and go on Jedi missions, which Troy Denning increasingly further genericized as purely commando strikes and StealthX fighter operations, in which all Jedi are blandly and uniformly competent.

Other prequel-influenced stories like Scourge, Fatal Alliance, Dark Times, Red Harvest, and Crosscurrent have struggled to make their Jedi protagonists stand out as characters. Their creativity seems crippled by adherence to the generic career-Jedi norm. Even the efforts to subvert that norm have been so hemmed in by uniformity as to spawn a new trope — the plucky-but-underpowered young female Jedi trainee who lacks confidence and worries about washing out. See Darsha Assant, Etain Tur-Mukan, and Scout.

In conclusion

The painful truth is that the Jedi-from-birth template, especially as exacerbated by Troy Denning’s tendency to run roughshod over any distinctions in Jedi roles in favor of making them interchangeable commando-pilots, produces cookie-cutter Jedi characters. They have the same life experiences and the same basic outlook. Their options for character definition are restricted by the removal of so many tools for diversification from the author’s toolbox, and the uniformity of the pattern discourages further innovation in all but the most creative authors. The unchecked spread of the Jedi-from-birth prequel model across the timeline and into authors’ heads must stop. It’s time for authors to return to diversity in background and role for Jedi characters. Their characters and stories will be so much richer when they do.

I’m fine with the Jedi-from-birth from model, but only as long as it remains where it belongs, in the era of the Republic’s decline and fall. Luke’s New Jedi Order should remain as dissimilar from the old as possible. The state of the old order pleasantly mirrors that of the Republic, as both grow into massive, ponderous (and a bit pompous) bureaucracies. The aftermath of the Galactic Civil War should trigger a reevaluation of the nature of the Jedi Order just as much as it should the workings of the galactic government.

No, no, no TLI – how will the audience be able to make sense of something different? Something that doesn’t fit neatly inside the box marked “Jedi Order”?

Remember this is a franchise that works on Highlander rules: There can only be one!

On a different tack, I found both Scourge and Crosscurrent to, at the very least, attempt something different with their Jedi leads.

Hmm Mander Zuma actually struck me as pleasantly refreshing, as he clearly had his own outlook on life and the force, especially as he was far from the typical in the field, brash hero Jedi, which given that he is a Liberian and also was one in his Pre-Jedi life makes sense, especially since Tionne was the one who trained him.

Scourge wasn’t a perfect novel, but it was definitely a big step in the right direction. I’d like to see more of Zuma.

Actually, I’d settle for Grubb writing another EU novel.

I first ran into this problem when someone asked my RP character what her interests were and I had to think long and hard for the answer, eventually answering with a flippant “lightsabering stuff.”

I don’t think it’s good for the characters either.

I don’t mind the Jedi from birth model or even there being a large amount of similarity among Jedi, since both approaches are natural ways for a pseudo-religious military order to be structured. In fact I think the high level of similarity, and the social disconnects it creates between the Jedi Order and the common people represent one of the more important weaknesses of the Jedi and something that should be retained.

I do agree that the ‘commando-pilot’ model is a problem, and a big one. In particular I blame the tendency to use, and to introduce characters through, Jedi in a ‘crowd scene’ context. After all, when you strip it down to brass tacks the Jedi ultimately do have a relatively similar set of combat abilities Corran, Kyle, and Jaina all still handle most of their problems either with a lightsaber or a starfighter. If you dump two hundred people into the middle of a gigantic combat sequence, such as Geonosis, no matter how diverse they internally the external appearance is going to be pretty conformist, whether they are Jedi or Commandos, or Senators.

I would much rather see the rarity of the Jedi (and for that matter their enemies the Sith, there was no need for the lost Tribe to have tens of thousands of members) serve as a way of fostering specialization. Jedi are really, really rare, especially in the NJO era, and their skills and abilities are precious commodities. They should be sent out alone or in very small teams and that sort of storytelling gives them a chance to develop distinct personal approaches to problems that occur.

As other commenters have mentioned this has worked with Mander Zuma and Jaden Korr, but it is not the primary approach. Instead there has been a tendency, going back to the beginning of the NJO series to treat the ‘Jedi Order’ as if it were a single combat unit that deploys large Jedi groups at one time. Doing so inevitably focuses on a small command team (usually the Council members) and produces a seemingly faceless mass of ‘troops.’

We should not have Jedi ‘troops,’ even in the Old Republic Era when the Order might have had a million members, certainly not for a few hundred Jedi in the New Jedi Order.

“If you dump two hundred people into the middle of a gigantic combat sequence, such as Geonosis, no matter how diverse they internally the external appearance is going to be pretty conformist”

I see your point, but it doesn’t have to be that way––Blast Radius did this right, I think.