Yesterday, we offered the first lesson and sublessons Star Wars could take from Assassin’s Creed. Today, we conclude with lessons two and three.

Lesson #2: Develop character arcs for every story

You wouldn’t think this would need to be a lesson . . . but can anyone tell me what the character arc of any major hero, besides Ben, has been since The New Jedi Order? The Expanded Universe hasn’t always been very good about making sure that its stories feature heroes going through arcs and receiving character development, rather than just pushing their way through another series of events.

One of the reasons I have enjoyed the Assassin’s Creed series is that its games have always avoided the temptation to be simple sequences of action setpieces. Storytelling has always mattered. Each of the series’ heroes has received an arc in each game. Desmond’s arc, stretched across his games, was to train as an Assassin, uncover the information he was searching for, and come to accept his place among the Assassins. Every game made sure to push that forward and add some new element, and even though his arc was the weakest of the leads’, the ultimate progression from bartender who had rejected his childhood as an Assassin to unwilling participant in the Assassin-Templar war to committed Assassin who ultimately sacrificed his life to protect the world based on his philosophical understanding of Assassin tenets was satisfying.

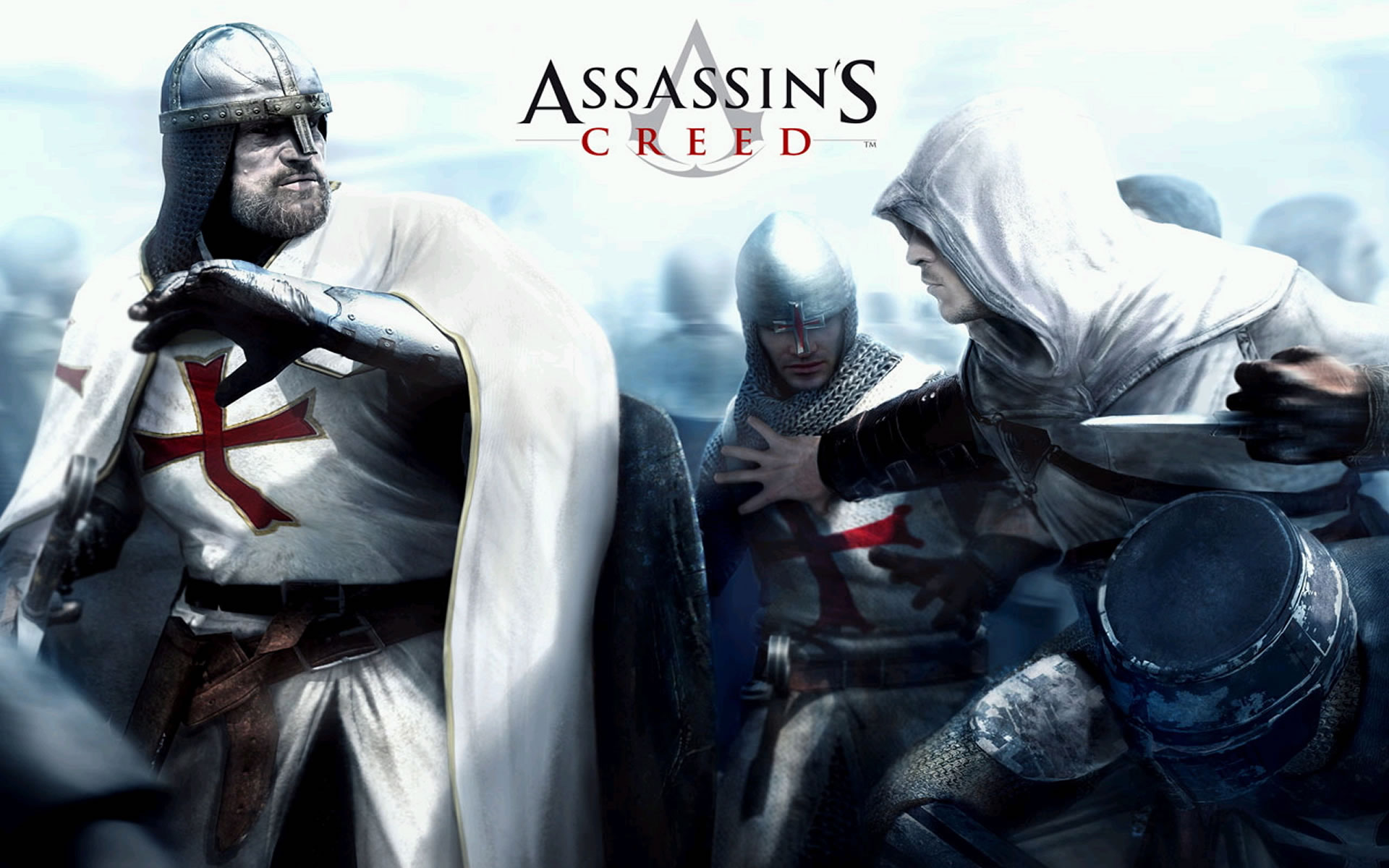

Altaïr, meanwhile, had a subtly revealed arc taking him from arrogant and dismissive of Assassin philosophy to philosophically engaged, humble, and respectful of others. He also had a nicely complex journey from dismissive of authority to respect of authority and ultimately to questioning of authority, a more subtle shift that did not move along a binary slider but involved changing his motivations, self-regard, and intellectual depth. Altaïr was later featured in flashbacks in Assassin’s Creed: Revelations, which made sure to give his life an arc of duty and sacrifice as he struggled to realize how to lead the Assassins and recover from crippling personal setbacks.

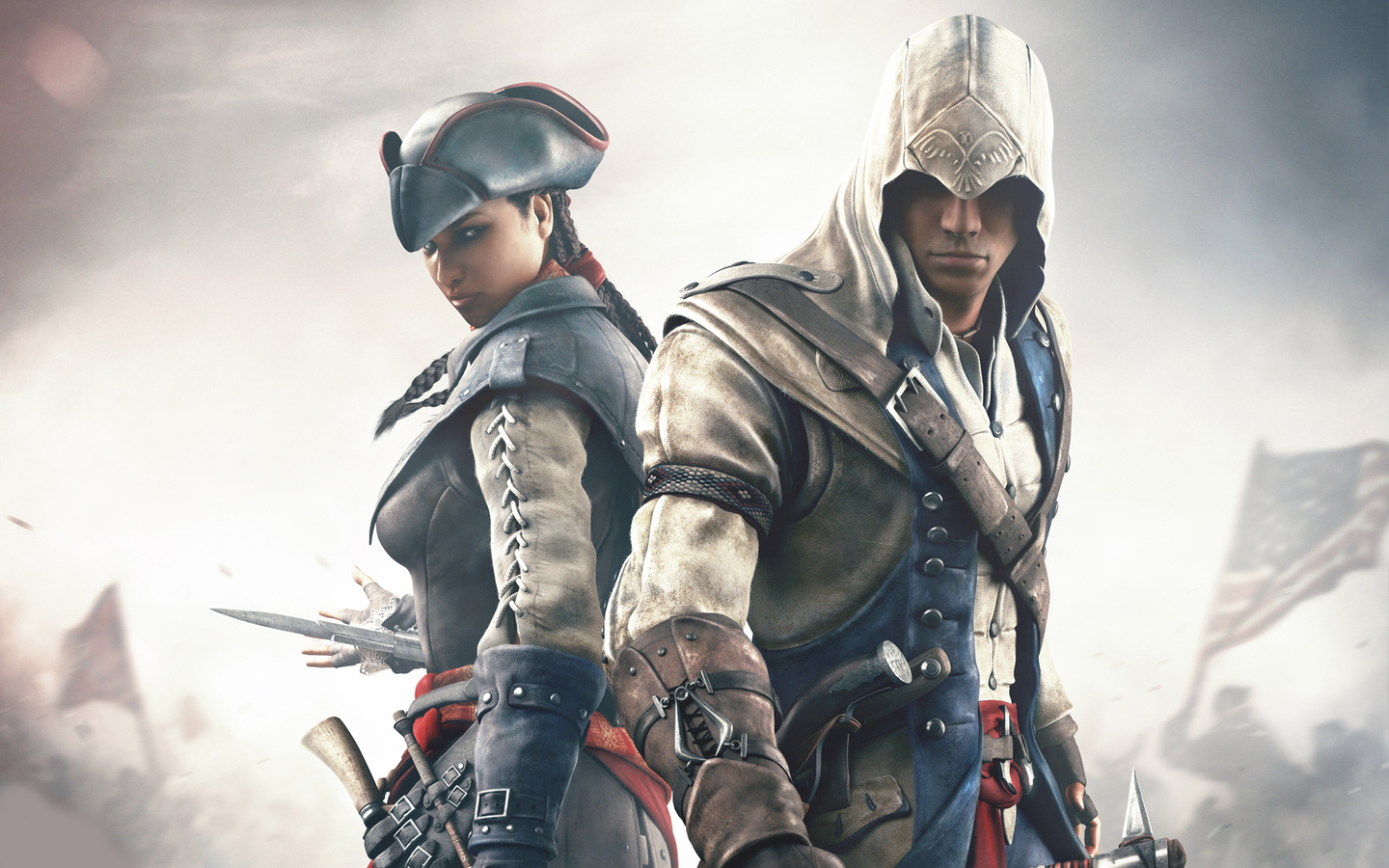

Connor’s arc was defined by his quest to find his place in the world. Born to a Mohawk woman by an English father, leaving his tribe to build a life in colonial America and engage Anglo-American society in the interest of his tribe’s safety, he was torn between two worlds throughout Assassin’s Creed III. His eagerness to figure out the right thing and do it combined with youthful anger and urgency to lead him into conflicts with his teacher over methodology, which didn’t come with simple answers. After his mother’s death, he built a surrogate family in his frontier homestead. In the end, Connor’s realization that he had no easy heroes to look up to, that the American revolutionaries, however good their ideals and intentions, wouldn’t bring his people the peace and security he hoped, and that his tribe had moved away west made him a man abandoned by both worlds he had been trying to fit into, confused and left the task of rebuilding his self-identity over again. It was a complex and challenging arc, one that showed writers eager to push their character and left him further opportunities to grow should he get sequels.

Ezio, with three games, could have stood still in the sequels, his arc completed after one game, in much the same way that the Big Three have been stalled for years. Instead, Ubisoft gave him some of the most impressive sustained character development of any leading character in a popular franchise. In Assassin’s Creed II, he was a carefree youth who was plunged into anger and confusion after the murders of his family members. He had to come to accept his place as an Assassin and learn to be a warrior. He also had to learn to let go of his quest for revenge, putting a dispassionate battle for ideals ahead of his personal anger. That game’s sequel, Assassin’s Creed: Brotherhood, didn’t leave him where he stood. Instead, just as Ezio’s transformation to an Assassin had given him an arc, his journey to leadership gave him a new arc, as the middle-aged Ezio grew into the role of Mentor of the Assassins after his uncle’s death. In Revelations, a fiftysomething Ezio, weary of a lifetime of fighting, was defined by his search for wisdom and enlightenment, which culminated in his decision that it was okay for him to retire and leave the fight against the Templars up to the other Assassins so that he could finally enjoy life and build a new family. Every time Ezio came back, it was with more character development, a new arc through which he could progress and grow. The writers knew that a story that was just about Ezio stabbing new people would ring hollow; if they were to chronicle Ezio’s entire life, it needed the emotional and narrative depth of a continuing personal journey throughout its entirety.

So do the lives of our Star Wars heroes. If Luke, Han, and Leia, and for that matter Jaina, are going to keep being at the core of stories, they have to keep developing as people. Character growth, emotional journeys, and narrative arcs aren’t just for a character’s first story; they’re for every story’s protagonists, and stories dedicated to advancing the universe’s storyline need character storylines too. If our characters can’t go through continued growth as consequential as Ezio’s, they shouldn’t continue being the protagonists for major stories.

Lesson #3: People will accept diversity if you give it to them

It has become a sort of conventional wisdom that video gamers are, in too great a proportion, racist, misogynist troglodytes who demand white male heroes just like them and reject female characters who are anything more complex than masturbatory fodder. Some of them may be, and some of them may be loud. Yet it’s noticeable that the Assassin’s Creed franchise has managed to be a blockbuster triple-A gaming property despite never featuring an Anglo-American lead until this year, in its sixth flagship game.

The series launched with Altaïr Ibn-La’Ahad, a Syrian Arab. In the freighted setting of the Third Crusade, he wasn’t a European Christian. Though the Assassins were politically neutral in the conflict and doctrinally irreligious, it was unmissable that the franchise’s “good guys” came from the cultural and racial “Other” in that particular conflict. Desmond Miles, in addition to being a second-stringer as a protagonist, was thus established at the beginning as, though American, not white-bread (indeed, his character model deliberately looked essentially identical to Altaïr’s).

The franchise followed him up with Ezio Auditore da Firenze, a Renaissance Italian. Though falling within the compass of what we would today consider a “white” European identity, Ezio was deliberately anything but your traditional Anglo-American white-guy video game hero. With his black hair, Mediterranean skin tone, thick accent, and frequent snatches of dialogue in Italian, Ezio was unmistakably “foreign.” It was his otherness that was emphasized, his placement in a culture distinct by time and space from that of American gamers.

Ratonhnhaké:ton, or Connor Kenway, was the protagonist of the first Assassin’s Creed game set in America. He wasn’t a white colonist. Instead, he was of mixed Native American and English descent. Raised within his mother’s Mohawk tribe, he self-identified as Mohawk and approached colonial society as an outsider, no matter how long he lived in it. He learned the ways of the Assassins not from a white man, but from Achilles Davenport, an elderly black freeman (and together, they served as the landlords and leaders of a bustling colonial community of outcasts on Achilles’s large estate). The protagonist of the successful companion game Assassin’s Creed III: Liberation, released on PlayStation Vita, was a black woman. Aveline de Grandpré, a product of the plaçage system of French-colonial Louisiana, had a French father, an African mother, and standing in society, as that game likewise addressed the intersection of race and colonial society. It is getting a higher-profile release on consoles and PC next year, further elevating Aveline’s prominence.

And all of the games starring these characters have been blockbusters, accompanied by no significant outbursts of racism, or in Aveline’s case, sexism. Indeed, fans had been clamoring for a female Assassin for some time, and Aveline was greeted with enthusiasm rather than the sort of “get your PC tokens out of my franchise” complaints conventional wisdom would predict. Fans likewise received Shao Jun, a female Chinese Assassin introduced as Ezio’s final protégée in the animated film Assassin’s Creed: Embers, with warmth and deep interest in seeing more of her story. Sales of Assassin’s Creed III did not suffer because it placed a person of color as the protagonist in a story of the American Revolutionary War. Assassin’s Creed launched the whole phenomenon with a protagonist who more closely resembled the terrorists America was at war with than the white-bread heroes of the Call of Duty megahits.

Overall, this suggests that audiences are much less racist and misogynist than they are suspected of being. As a whole, they are better than they are given credit for, and when their supposed prejudices aren’t pandered to, the world does not end and, importantly to studios, the product does not flop simply because of it.

Yet such concerns can’t be dismissed; we have seen incidents of the sort of backlash and backwardness on which the conventional wisdom is based, and studios of all kinds still appear convinced by and large that the American and Western public won’t accept anything other than conventionally Anglo male heroes in its blockbuster franchises. What has allowed Assassin’s Creed to get away with bucking conventional wisdom?

I would argue two main factors are at play in smoothing diversity’s passage. Assassin’s Creed doesn’t make a big deal of its racial diversity, and it inserts it in a way that is so built-in to the story and natural-appearing that it hardly even occurs to the audience to question it.

Ubisoft hasn’t spent a lot of time publicly patting its own back about how progressive and enlightened its franchise is — nor acting defensive about its choices. It just presents its characters and leaves it to the audience to notice or not notice that the head of the Revolutionary-era American Assassins is a black man, or that Edward Kenway’s first mate in Assassin’s Creed IV: Black Flag is an African. Liberation was accompanied not by statements about how groundbreaking its woman of color protagonist was, but by statements to the effect of, “Aveline is our protagonist and we think she’s cool. We think the intersection of race and colonial culture is a pretty interesting ground for storytelling, so that’s where we went.”

This may sound like it’s pandering to the chorus of people saying, “I don’t want these PC tokens crammed down my throat,” but I’m not talking about trying to take away that excuse — it’s too irrational a response for that to work. Instead, what I’m talking about is the idea that the best way for something to not be controversial is to not act like it’s controversial. Do it without comment, don’t be defensive or self-congratulatory, and it will fly under the radar. Present something as uncontroversial, and fewer people will feel provoked to engage in controversy. It may, in fact, be the best way to gain acceptance, gain converts, and normalize diversity — by quietly presenting it as normal, uncontroversial, and entirely unexceptional to those people who are on the fence or simply not thinking deeply about the issue, rather than as part of some kind of campaign directed against or at them. It’s simple psychology that acting like something is the case can have a powerful effect in normalizing the idea that it is the case, and those in the middle may be best reached by sliding around their defenses entirely.

Secondly, and significantly, Assassin’s Creed offers a context in which its diversity seems perfectly logical. The first game was set during the Crusades, in the Holy Land; of course it would feature Arab characters. The actual historical Assassins were a Middle Eastern group, thus it is unimpeachably logical that the game should star an Arab. Liberation was set in colonial Louisiana, home to the actual plaçage system; what could be more natural than addressing the issue of slavery and including a mulatto protagonist? Assassin’s Creed III built its entire story around Connor’s native heritage, making it silly to question the idea that Connor could be anything but of Native American descent. Criticism simply rolls off the games as facially absurd; it would be as unthinkable to ask why Assassin’s Creed: Brotherhood didn’t star Americans in Renaissance Rome as it would be to ask why The King’s Speech didn’t star a Vietnamese George VI.

Now, these aren’t techniques that can be applied to all stories — it would simply narrow the presentation of diversity too much, and harm the cause of advancing it, to try to make it always innocuous and unimpeachably necessary. But they do offer some ways for Star Wars to approach the issue going forward. The sequel films, for example, have an flawless route to presenting a major character of color: include Lando’s daughter as a major figure in the cast and there’s no room for controversy about her inclusion. Give viewers Lando’s kid and they won’t think twice, because there’s nothing to think twice about. Lando had a kid and she’s in the movie; just like Han and Leia. She’s black? Well, of course.

Similarly, if the EU or sequels want to give Luke a Hispanic apprentice, or if Donald Glover is the voice of the lead kid in Rebels‘ ensemble, or some original work endows a new female Ithorian Jedi lead with a Toshiro Mifune-esque mentor figure, the less clamor is made about it, the less audiences will think it’s anything to make a clamor about.

Be bold, quietly give people diversity without straining for attention, and make it seem as natural as possible, and it will be accepted a lot more peacefully than conventional wisdom suggests. Assassin’s Creed shows that it can work, and like all the other intellectual property owners, Disney and LFL need to take the lesson that the only thing really holding them back from diversity isn’t audience hostility to the mere concept of diverse lead characters, but their own cowardly and narrow perception of conventional wisdom.

One thought to “What Star Wars Can Learn From Assassin’s Creed, Part 2”

Comments are closed.