The best part about choosing topics for Not A Committee, Eleven-ThirtyEight’s group format, is that sometimes I’m not sure how I feel about an issue myself. When I read this article on Vox a few weeks back, highlighting what’s known as the “Despecialized Edition” of A New Ho—ah, I’m sorry, Star Wars—and lamenting the fact that such exhaustive fan work can only be distributed in defiance of the law, I could see both sides of the issue. Not that I was clamoring for Star Wars to become public domain necessarily, but us dedicated fans are so used to talking about the franchise as modern mythology, the contemporary equivalent of Beowulf or The Odyssey, that we can kind of take for granted the fact that nobody owns Grendel and Odysseus, while Luke Skywalker is someone’s property—for a long time one specific person’s property, and now the property of one monstrously huge and mercilessly ligitious corporation.

So as I am empowered to do in these situations, I farmed it out. I put the question to the staff, in these exact words: “is there an argument to be made for ANH (at least) to be in the public domain, either by now or at some definite point in the future? Should Lucasfilm be able to own it for eternity, or does its cultural importance mean it should belong to everybody?”

While the complexity of this issue was one easy consensus to reach, the breadth, and content, of their answers were certainly an education.

Alexander: If the question is whether A New Hope should be in the public domain right now, my answer would have to be no. Even going by the United States’ oldest and most generous copyright terms (Copyright Act of 1790!), it would have entered the public domain as far back as 1991, less than a decade after Return of the Jedi, or 2005 had it been renewed for a second term, which it almost certainly would have been, making it freely available just in time for the release of Revenge of the Sith and the conclusion of the prequel trilogy.

If we’re thinking of special exemptions from copyright law, while the film undeniably possesses many remarkable and noteworthy elements, I don’t think any of them make it any more deserving of entering the public domain than, say, Smokey and the Bandit, Saturday Night Fever, The Spy Who Loved Me, or any other popular and beloved movie released in 1977. And as for the character of Luke Skywalker specifically, there are a great many far older characters that I’d like to see available for the general public long before him (Batman? Superman? James Bond? Miss Marple?).

Now, if we’re going to talk about if and/or when A New Hope should enter the public domain, that’s a somewhat thornier issue. Copyright terms have lengthened dramatically since they first came into existence, from the absolute maximum of 28 years mentioned earlier to their present state, set at the duration of the author’s life plus an additional 70 years (95 years from publication or 120 years from creation for works made for hire, whichever is shorter). The Walt Disney Company had a significant hand in the most recent extension (and possibly others) in order to preserve its ownership of a certain iconic pair of mouse ears, and I have absolutely no doubt that they will do the same for the Star Wars franchise, and will continue to do so for as long as the corporation exists.

So the question, then, is not quite so simple as being whether or not A New Hope and its characters belong in the public domain. It can’t be that simple. It’s a question of what function we want copyrights to serve, of how long they should last before expiring, and of who we want to benefit from their existence. On a broader level, it’s also obviously tied in to the issue of what degree of corporate influence is permissible or desirable when it comes to the legislative process. And, of course, as in most things, there are valid arguments to be made by both sides of the debate.

So the question, then, is not quite so simple as being whether or not A New Hope and its characters belong in the public domain. It can’t be that simple. It’s a question of what function we want copyrights to serve, of how long they should last before expiring, and of who we want to benefit from their existence. On a broader level, it’s also obviously tied in to the issue of what degree of corporate influence is permissible or desirable when it comes to the legislative process. And, of course, as in most things, there are valid arguments to be made by both sides of the debate.

Some feel that copyright laws stifle creativity and promote undesirable monopolies on ideas, and that old works and new content creators alike could benefit greatly from the opportunity to explore their stories and characters in different ways as so many have done before with the likes of Sherlock Holmes and Dracula, or King Arthur and Robin Hood, or Shakespeare. The idea being that we could easily see dozens or hundreds of new versions of classic characters’ adventures and crossovers, and that old and mostly forgotten works could reach and be appreciated by new audiences through free digital distribution.

Others believe quite that opposite, stating that it in fact promotes creativity by preventing new writers from relying too heavily on preexisting works and ideas, and that allowing more stories into the public domain would leave the market flooded by cheap imitations and spinoffs that would only serve to taint the original works by association. That Lucas had to create Star Wars because he couldn’t get his hands on the rights to Flash Gordon is often cited in favor of this particular argument.

Some consider the current state of copyright law as having been taken too far, and see it as no longer having any relation to the function it was originally intended to serve. Patents, for example, still only last for 20 years before expiring permanently, compared to copyrights that near a century in duration. Others prefer to interpret it as having evolved into something more suitable for the times rather than having been warped (especially with regard to the increase in life expectancy since 1790), and feel that it’s necessary to continue extending it in order to properly incentivize the creative process and provide for authors’ heirs.

And even after all of that, we’ve not yet even touched the international side of things, where works may enter the public domain in some countries but not in others if their copyright terms differ, such as a recent case where James Bond become freely available in Canada (a situation not likely to last long, however), to say nothing of how potential changes would affect the music industry (and many others), where the subject of copyright (and its merits) has often been vigorously debated.

I do not believe that A New Hope and Luke Skywalker are sufficiently culturally significant as to warrant placing them in the public domain above and beyond all other similar works. I do believe that if it should ever enter the public domain, then it should do so hand in hand with every other work of and before its time. Whether or not that should happen now, in the future, or ever? That’s a question I’m not even remotely equipped to ask, let alone answer. That, I’ll leave to the corporations and courts to sort out.

Ben C: For the most part, most of the time, I would likely back the idea that the copyright on a story should stay with the artist who created it. A rare exception would be where heirs of artists are concerned – I’m not really won over by the argument that Jack Kirby’s kids should get a large amount of compensation for the bad deals Kirby signed when alive and got screwed over on. It feels like benefiting from someone else’s work and achievements. The other very rare exception, where I’d be tempted not to back it, would be when an artist has behaved with a staggering level of contempt and disrespect for their own work that it warrants intervention by the state to stop it!

Who would qualify for this category? It has to have some very hefty qualification criteria – the work must be deemed a classic of its medium, it must be staggeringly popular and have changed how stories in its medium are told. For me, Star Wars: A New Hope fits all three and its creator, George Lucas, has over the last engaged in such wanton artistic destruction that the protection afforded by copyright should not apply.

But Lucas and his company own the film, don’t they? Yes, they do but Lucas’ antics over the legacy of A New Hope seriously undermines the idea of absolute artistic licence. We can look to the example of Blade Runner, where there is about 3-4 versions of the film, but its director Ridley Scott, is quite relaxed about. This is in sharp contrast to Lucas, who went so far as to destroy the original negatives of A New Hope! Lucas’ attitude to artistic licence is to say that he had the absolute right to determine what versions of his films the audience saw and to do anything to them. Had all those revisions been positive no one would care, but a few of them are akin to painting a big black moustache on the Mona Lisa and then claiming it looks better. Such an act would likely be seen as artistic vandalism.

But Lucas and his company own the film, don’t they? Yes, they do but Lucas’ antics over the legacy of A New Hope seriously undermines the idea of absolute artistic licence. We can look to the example of Blade Runner, where there is about 3-4 versions of the film, but its director Ridley Scott, is quite relaxed about. This is in sharp contrast to Lucas, who went so far as to destroy the original negatives of A New Hope! Lucas’ attitude to artistic licence is to say that he had the absolute right to determine what versions of his films the audience saw and to do anything to them. Had all those revisions been positive no one would care, but a few of them are akin to painting a big black moustache on the Mona Lisa and then claiming it looks better. Such an act would likely be seen as artistic vandalism.

The problem, however, is exception cases tend to make for bad laws, because law has to apply so far beyond individual cases. Law sets the standard for all cases. I have massive problems with the way Lucas has treated his creation over the last two decades, but is declaring ANH to be public domain property really the solution? Given all that could flow from it? There’s plenty of companies that’d love the idea of no longer having to negotiate with creators. For all that the Lucifer TV pilot sounds horrendous, it would be worse if that particular incarnation of the character was public domain. Or they could get their corporate paws on Saga….

So the better solution to Lucas’ hubris? Arguably that what has already happened to him. Lucas is arguably a perfect case study of how not to handle success and a massively popular franchise. Star Wars now continues to be successful in spite of Lucas’ destructive and perfectionist tendencies, not because of them. Nor would I put it past Disney to grab a load of laserdiscs, subject them to a massive restoration and remaster and then release them as Star Wars: the Original Editions. The demand remains, it is not going away, that is a clear market incentive to supply them… Without changing copyright law!

There would also be a certain poetic justice to such a move too as Lucas would be unable to do anything about it. After all, he sold SW to Disney lock, stock and barrel! The same protections that permitted his destructive approach would enable a restorative one by Disney.

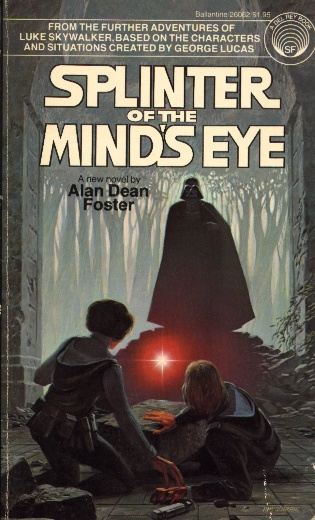

Rocky: One of the taglines for the Star Wars universe that really struck me comes from the front cover of Splinter of the Mind’s Eye. Yes, that book. And the line is “based on the characters and situations created by George Lucas.” It gives Star Wars the feel of a more collaborative universe, a perhaps prescient view of how many more authors and artists would contribute to the success of Star Wars. By now, Star Wars is a modern-day myth that almost everyone familiar with American popular culture has heard of in some way, and with Star Wars being bought by Disney and being brought back to the screen, we’re in a new era for this franchise.

Disney’s purchase is the thing that is going to keep Star Wars out of the public domain for a good long while. They’ve breathed new life into a universe that, while going, wasn’t doing anything truly revolutionary. And they’ve answered beyond fans’ wildest dreams, for better and worse. The characters and situations we’re so familiar with are going to be coming back; the next generation’s Star Wars will have the same essence as the universe we grew up on. The very fact that the franchise is continuing helps elevate it to being a true icon of popular culture. How many versions are there of Star Wars, how long of an argument can you have about which is the best, and will we ever see one definitive version? Almost definitely not.

Disney’s purchase is the thing that is going to keep Star Wars out of the public domain for a good long while. They’ve breathed new life into a universe that, while going, wasn’t doing anything truly revolutionary. And they’ve answered beyond fans’ wildest dreams, for better and worse. The characters and situations we’re so familiar with are going to be coming back; the next generation’s Star Wars will have the same essence as the universe we grew up on. The very fact that the franchise is continuing helps elevate it to being a true icon of popular culture. How many versions are there of Star Wars, how long of an argument can you have about which is the best, and will we ever see one definitive version? Almost definitely not.

There is no real need to allow Star Wars into the public domain. It’s going to continue on for many years, and with the amount of fan work, parody, commentary, and officially licensed media, we’ll have no shortage at all of Star Wars. It’s thriving all the more under its new owners, and they aren’t going to let such a valuable franchise into the public domain. Furthermore, though Star Wars is well-known and distinctive, it would be odd to let it into public domain before things like Batman, Superman, and many of the older Disney movies. Much of what’s in public domain now is also very well-known culturally, but has many different interpretations depending on the individual authors and artists working in that particular universe. Star Wars still has well-defined parameters for how its universe looks and feels, and it’s understandable to want to retain tight control of how the franchise develops especially at such a time of growth.

Mike: With persistent (though unconvincing, in my opinion) rumors of an impending official release of the unedited original trilogy, one could be forgiven for thinking that it’s only a matter of time before the creators of the Despecialized Editions get what they want anyway. Having seen just how much they’ve put into their version of a definitive Star Wars experience, though, one thing is clear to me: no official release will ever be enough. There are too many, let’s be honest here, blatant flaws in the movie and its subsequent revisions to ever reach a consensus on just what “definitive” even means—it’s one thing to take out the CGI, but do you ignore the miscolored lightsabers and the garbage mattes? Or the vaseline blob under Luke’s landspeeder? How do you feel about the English text on the tractor beam controls? The stormtrooper bumping his head?

And of course, that’s completely discounting Special Edition babies like myself whose formative experience with the movie was an altered version, and who remember it (mostly) fondly? Do we not count because we didn’t happen to see it before 1997?

So while I admire the effort these fans are putting in, and in some cases I’m flat-out in awe of what they’ve been able to accomplish, no, I have no special need for their distributing it to be legal. It’s hardly the most illegal thing happening on the internet. And the thing about Luke Skywalker being a figure of mythology is, culture is stronger than law. It doesn’t really matter how copyrighted he is. We’re gonna play around with him anyway.