Welcome again to The Force Does Not Throw Dice, our section about the wonderful world of running tabletop roleplaying games set in the Galaxy Far Far Away. No, this piece is not about gaming in what is known as “the prequel trilogy era”. What we are going to be talking about is how to set up a prequel campaign to your existing campaign. So dust off your Jar Jar sipping cup, find your old Y2K survival kit, play your least-hated Limp Bizkit CD… and let’s game like it’s 1999!

First of all: I’m perfectly aware that, out of the many words that are likely to elicit strong reactions from the fans, the two most powerful ones are probably “canon” and “prequels”, but this article is not going to get into whether the idea of Star Wars prequels was pure genius or a regrettable mistake. I have my own personal thoughts on the matter, of course, but it’s completely undeniable that the existence of prequels has become one of the most important or at least one of the most popular facets of Star Wars storytelling. So, if one of our objectives as GMs is presenting a faithful “Star Wars experience” in our RPG, why not bringing this to the table? So let’s work together and see how we can make our own prequel game.

Before taking a look at how to run a prequel, I’m going to make a few assumptions here. First of all, I’m assuming that you’ve had a “source campaign” running for a while and that you’ve created enough lore and characters to draw from: to be able to create a prequel, you need some kind of original work first! Second, I’m also assuming that we are talking about a “prequel” purely in the manner of the Star Wars prequel trilogy: we are not talking about a series focused on the childhood of the current characters or about a distant prequel set in the Old Republic or even before that, but a prequel set one or two generations before the current series. Third: in an effort to make this article as useful as possible, I’m assuming that the prequel campaign is going to be either a one-shot game or a short campaign, but there’s nothing stopping it from turning into a long campaign or even completely supplanting your original game: it happened to me, and it actually was the best Star Wars campaign I’ve ever directed. But I’m being realistic: it’s hard enough to get a campaign running, so I’m assuming you will be more likely to run a one-shot between adventures. Most experienced GMs are not really going to need any of this advice, but I still hope that they will find a few useful ideas in here!

So let’s say you—both the GM and the players—are a bit tired of your current campaign and maybe looking for a change. Or your group has arrived at a place where it would make sense to stop your game for a while, like the defeat of a major villain or a long period of downtime. Or maybe you just want a change of pace for a weekend, or maybe playing a prequel game just sounds like a fascinating idea. Whatever reason you have, you’ve decided that you are going to play a prequel to your current campaign. So let’s take a look at how best to do this—as usual, I’m just going to be giving some pointers and guidelines based on my experience on the topic, and I hope that even if you completely disagree with my approach you will find this piece somewhat interesting.

The prequel storyline

Every time you start a new game, it’s a good idea to ask yourself: what, exactly, am I trying to do here? I love spitballing campaigns, don’t get me wrong, and some of my best games have been completely improvised (here’s some good reading on the topic) but it’s rarely a good idea to go into a prequel game with no previous preparation at all. It’s too easy to trip on yourself and to find complications that some prep time would have made easier to avoid.

So, other than obviously having fun, what do you want to do? Are you most interested in telling the backstory of your game? If your original storyline was about the destruction of an Imperial superweapon, maybe you want to take a page out of Rogue One and play the story of how it was built. Or do you want your prequel to be more character-oriented? If one of the player characters is always blabbing about the crazy adventures of their defunct parent or master, maybe you think it would be funny to see them in action.

Although you are most inevitably going to take a bit from column A and a bit from column B, I recommend starting focused on character rather than plot. It’s very hard to play a prequel focused on existing plots without falling into that annoying GM vice that we call railroading. What if the new team destroys the superweapon twenty years before it was supposed to be destroyed? What if they murder someone that was supposed to help them in the future? While it’s still perfectly possible that a character-oriented prequel falls into this kind of temporal paradox, the backstories of these characters are rarely as developed as the plot of your original campaign was. What are the chances that any of your players spent more and time and effort describing the life of their character’s mother than you did explaining all the power and capabilities of your Imperial superweapon and that you all spent playing through it? Take the path of least resistance to build the foundation of your game.

And when it comes to referencing the source campaign in-game, remember that one time we talked about VIPs and apply here everything that we learned there: you need to elevate the original PCs and NPCs to VIP category and thus use them sparingly and carefully. You can even look at it this way: your source campaign has become a VIP itself, so you should make any connections to it brief, relevant, and well-planned. If you really want to establish plot connections between both time periods (after all, it’s the Star Wars prequel mold) work the other way around: use the prequel series to seed some plotlines that you know you will be able to expand when you resume your regular game. You’ll avoid a lot of headaches this way.

Creating family sagas

When we talk about sagas here, we are talking about stories that chronicle the lives of the members of a family or several interconnected families over a period of time. The main Star Wars movies are obviously patterned like sagas—they are literally called “the Star Wars saga”. The Skywalker family is the focus of this saga, going from Anakin to Luke and Leia to Ben Solo, but there are many other families involved: we have the Fetts, the Syndullas, the Ersos, the Huxes, and in the Legends continuity we had even more, like the Antilles, the Fels, the Halcyons, or the Darklighters. If our objective is to build a prequel in the spirit of Star Wars, we should conceive of it as part of a saga.

So where to start with our saga? Should every player play a parent or older sibling of their current characters? I can only think of a few scenarios where that would feel natural. I once ran a Middle-earth Roleplaying Game campaign that focused on the offspring of a group of veterans of the War of the Ring who had gathered to finish a task their parents hadn’t been able to finish, so it was already established that their parents had worked together in the past, but this kind of situation is not going to be the norm. There’s always a big risk with prequels, perhaps an inevitable one, and that’s shrinking your universe by shrinking the network of acquaintances of its inhabitants. If the parents of every single character somehow also knew each other in the past, your galaxy suddenly feels more like a small countryside town than like an almost infinite canvas of billions of worlds. That’s not an effect you want. Sure, the Star Wars prequels sometimes fall into this–having Anakin be the builder of C-3PO, for example–but I’m not going to be criticizing that narrative choice: let’s just say that, if you think that that kind of thing works, it works because George Lucas is George Lucas and can get away with it. Chances are you can’t.

When I first ran a prequel series, I had been running a game with five players for just one year. Things were getting a bit stale, so I suggested playing a prequel, an idea that everyone loved. I sat down with my players to help them create their new characters and I gave them one guideline: I was okay with one or two of them playing their characters’ parents or mentors, but no more than that. I also told them that I was okay with another one or two of them playing the parents or mentors of any NPCs in my campaign. But the other two had to be completely new characters, unrelated to anything we had played before. Since then this has been my rule when it comes to prequels: one-third maximum can be related to PCs, one-third maximum can be related to NPCs, the rest have to be completely new. I’m not saying that this should be a strict rule in your game–I actually encourage you to be flexible if you think it will work better–but consider the effect a guideline like this has in-game: it creates connections to the source campaign but doesn’t go too far. It keeps the universe as large as possible while still creating continuity between two eras of play.

When I ran that first prequel campaign, I also decided to add an extra rule: all “legacy characters”–that is, characters related to an existing PC or NPC–had to be mechanically distinct from their future offspring. The way to do something like this changes from system to system: under D6 it would mean using different templates, in d20 it would mean that their main base class had to be different, and playing the current FFG incarnation I would probably say that they had to choose at least a different specialization for their characters. By doing this, I intended to help the players make their legacy characters as distinct from their future offspring as possible; honestly, my group at the time needed this kind of help–all kinds of help–when it came to roleplaying, but I’ve come to appreciate the way that a rule like this can help the prequel campaign stand apart from the source campaign, so I still invoke it from time to time.

Let’s see how this worked out the first time I ran a Star Wars RPG prequel. Our game was set in the Rebellion era, and we decided to set the prequel a couple of years before Episode I. The first player created a smuggler called Roark, the father of his usual character, Rayman the bounty hunter. The second player decided to go with the parent of an established NPC, thinking that it would allow for more leeway and creativity, so he rolled Hank, the father of an NPC he particularly liked, a bounty hunter called Jaan. Player number three came to me with a different idea himself: he actually wanted to play an existing NPC when he was just a kid, inspired by little Anakin and little Boba; the NPC he chose was a minor one, a Rebel Alliance colonel that had appeared in one single adventure, and the player seemed really excited about the idea, so I decided to allow it–remember what I said about being flexible?

The other two players rolled completely new characters, both very different from what they were playing in the regular game. Would I have relented if they had insisted on playing legacy characters as well? If I had thought they wouldn’t have enjoyed the game otherwise, yes, I would, but I would have asked them to make the connections as indirect as possible. Thankfully, I’ve found that most players are more than happy to play ball when it comes to prequels, and I’m always willing to throw out some “continuity morsels” like having the prequel group visit the homeworld of one of the “left behind” characters.

Thus our prequel adventuring group had strong connections to the existing game, but nothing was too farfetched. Could we buy that the parents of one of the PCs and the parents of a not very prominent NPC knew each other when they were younger? Sure, seemed like the kind of coincidence that could happen. Could I buy that the original characters once briefly ran into some guy their parents knew? Yeah, totally. Everyone was happy with the set-up. I successfully managed to keep the suspension of disbelief up, and that’s always a win.

The George McFly Clause

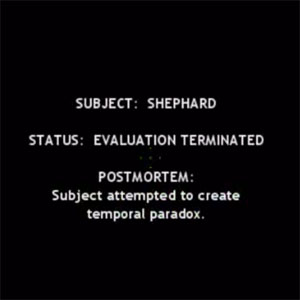

I bet you are thinking this: “so, if I’m playing one of these legacy characters and a stray blaster bolt hits their very delicate face, and my character dies before being able to conceive the future hero of the Rebellion that I play in my regular game… isn’t that kind of a problem?”

Yes, of course, and a pretty big one! After thinking it over, I talked to all of my players before starting the game and asked them if they agreed with this little clause: “if a legacy character is killed, that character will somehow manage to survive but the player will have to roll a new one.” So if Roark was killed in a firefight before conceiving his son, Roark would actually survive the experience but be seriously wounded, maybe even spend a few months in a coma, and once the ordeal was over he would stop being a player character: he would retire, maybe unable to continue a life of adventure. Roark’s player would have to roll a completely new, preferably non-legacy, character.

It’s pure metagaming, no doubt about it, and it sure can be a sour pill to swallow for the sector of players that argue strongly for “realism” and “verisimilitude” and constantly rail against things they consider to be “too gamey”, but ask them to consider the alternatives: would they prefer moving the whole prequel to an alternate universe? I mean… if you all are okay with that, more power to you and your group, but I find that it takes away from the charm of playing a prequel. Personally, I’d rather agree on this “George McFly Clause” beforehand and never have a lucky shot destroying the space-time continuum (Great Scott!)

And that’s it!

Seriously, there’s actually not much more to this. Once you’ve done your homework and made sure that most of the obstacles to enjoying a prequel campaign have been taken care of, you can run your game as any other game you’ve ran before. You can make it as linear or sandboxy as you want. You can hint at future developments, play with the players’ expectations (who knew the evil Imperial admiral was a dreamy-eyed farmer when she was young?) and let them see the past of their games. I’ve ran multiple prequel games for different settings and systems, and they are always a blast! Just remember the golden rule: as long as the game is fun, you’ve done your job right.

Loved this.

For mine, we did a few rounds as the beginner characters and started crafting our own. I felt like the villains I had designed were a little bland, so I took a step back and decided that we would play an origin story for them. (The lead was a Nelvaniaan who had some control of the Dark Side and a lost Inquisitor saber, and three specialist Stormtroopers.) To boost the main campaign, I assigned them the roles of the Stormtroopers and let them decide what they would be like. When we moved back to our original game, they really liked the new characterization they had given their enemies. I was able to curb their ability to predict what their former character would do by throwing them all in such crazy situations they didn’t have time to think ahead.