I am a woman conflicted.

I was relentlessly eager for Claudia Gray’s Master & Apprentice, but once it was released, my enjoyment of the work was overshadowed by my childhood love for Jude Watson’s Jedi Apprentice series.

I feasted on the rumors and then the announcement of an Obi-Wan Kenobi series, but at the same time, I’m not ready to say goodbye to John Jackson Miller’s Kenobi.

I want to set Del Rey up on a blind date with author Ann Leckie to bring the Young Satine Kryze novel we deserve into being, but I dream of this while clutching the Schrödinger’s canon of A Star Wars Comic‘s Satine issue to my chest.

I am not unique in these anxieties. Even if it’s not these particular characters and these particular stories, everyone has pieces of Star Wars that they want to see the light of canon. Perhaps it’s something that people want to see make the jump from Legends or theories that they want confirmed. Engaging with stories is always personal, and while critiquing the work we consume is important, there’s also a space where we must be willing to let go and accept the contradictions between our expectations and the stories created by other, equally invested people.

A good practice ground for engaging in these contradictions is the robot stories of Isaac Asimov.

Isaac Asimov was a Jewish immigrant who became one of the most prolific writers in America. While he is mostly famous for his science fiction, he also had a great love for mysteries and satire. His body of work – over five hundred published books [1]Blackwood, B. D. (2010). Isaac Asimov. Critical Survey of Long Fiction, Fourth Edition, 1–4 – stretches to include non-fiction for nearly every section of the Dewey Decimal system. My own personal Asimov collection includes gems like Familiar Poems, Annotated and An Easy Introduction to the Slide Rule.

Early on in his writing career, Isaac Asimov found disdain for one of science fiction’s common themes: the robot uprising, referring to it as Robots-as-Menace or the more famous “Frankenstein Complex”. He found the notion distasteful, that scientific advancement was “playing God” and a punishable sin. His Three Laws of Robotics were created (along with the accidental invention of the word “robotics”) in order to emphasize the notion of robots as tools created by man [2]Asimov, Isaac. “Robots I Have Known”. Robot Visions. 1990. Originally published in Computers and Automation, 1954.

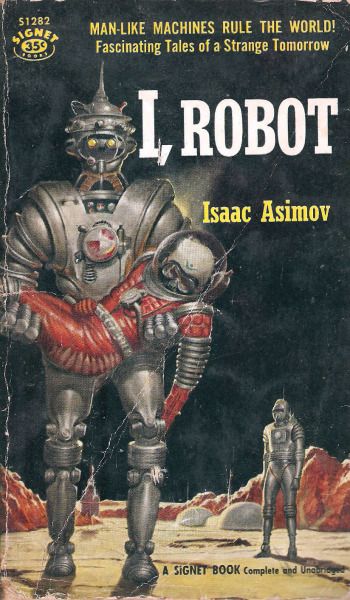

The Three Laws weren’t fully introduced until the fourth robot story Asimov wrote, “Runaround” [3]Asimov, Isaac. “Introduction”. The Complete Robot. 1995. which meant that “Robbie,” “Reason,” and “Liar!” had to be rewritten to reference the Laws explicitly when they were collected into the book I, Robot. Published in 1950, I, Robot connected these stories through a newly-written framing device of an interview with principle character – Dr. Susan Calvin – tying her to stories in which she previously had no part.

I, Robot is frequently regarded as the first of Asimov’s works in his Robot series, but by picking it apart, we can see that the “canon” doesn’t have as solid a foundation as fans might be used to today. Perhaps the original versions of his first three stories are merely Early Installment Weirdness rearing its head. After all, Dr. Susan Calvin became the binding agent of most of Asimov’s robot short stories. Along with the duo of Powell and Donovan, her appearance serves as an acknowledgement that these stories took place in the same universe. However, the rest of the novels in the Robot series took a different route.

For a time, it appeared that the Robot mysteries were not set in the same universe as the short stories, despite relying heavily on the Three Laws. There didn’t seem to be any acknowledgement of the adventures of Calvin or Powell and Donovan. As the novels continued, however, sly references to the short stories were slipped into place, namely repetitions of problems and archetypes. Then in Robots of Dawn, the name of Dr. Susan Calvin was dropped, not as a historical figure, but as a mythological one. Suddenly, Calvin and all that she brought with her were irrevocably made a part of the novels’ universe, even if presented as mere fables.

Asimov seemed to treat the canon of all his robot stories with this same type of fluidity. “The Bicentennial Man” and “Segregationist” are stories that could be set in the same universe, but don’t fit neatly with either Calvin’s tales or the Robot mysteries [4]Andrew, the titular Bicentennial Man, is also referenced as a mere myth in Robots of Dawn. With “…That Thou Art Mindful of Him” and “Cal”, Asimov flirts with the notion of a robot uprising, the very thing he created the Three Laws to avoid. When considering any potential pushback from such developments, Asimov’s response was effectively “my house, my rules”. [5]“…there is more than a hint of Robot-as-Menace. Well, if I want to do that once in a while, I can, I suppose. Who’s there to stop me?” – Asimov, Isaac. The Complete Robot. 1995. Quote … Continue reading.

At the end of the day, the stories of Isaac Asimov’s robots are not beloved for their interconnectivity, but rather for the ideas they explore. Many of them could be boiled down to “Three Laws Troubleshooting” but even those are rarely a simple puzzle story. They ask questions about mortality, humor, arrogance, compassion. They reflect something of ourselves – we flawed humans with no Laws to control our free will. It would be foolish to throw out the richness of stories like “Bicentennial Man” or “Cal” simply because they didn’t fit with the ongoing stories of other characters.

And this is the lesson: new canon contradicting the stories I loved from Legends or fan fiction doesn’t mean I have to say goodbye. It’s not just a matter of being able to return to the books but understanding that, as displayed by Chris Wermeskerch’s Legendary Adventure reviews, there’s value to be had in the return. That there’s “always a little truth in legends.” Lucasfilm itself seems to be leaning into this value of these stories. They aren’t just pulling in the legends of Legends like Thrawn, but between From A Certain Point of View, The Legends of Luke Skywalker, and most recently Myths & Fables, it’s like they’re encouraging people to play with the fluidity of canon.

Interconnectivity is fine – important, I would even argue in some cases – but the stories we cling to are ultimately beloved not because they’re piles of references. Canon, Legends, or fanfic, these stories are beloved because they reflect something of ourselves.

Master & Apprentice can’t take away the catharsis that Jedi Apprentice‘s Obi-Wan gave me as a child. Annileen and her Casablanca world of Tatooine will still be waiting for me in the pages of Kenobi. And Satine casting away her bowstaff like Luke Skywalker could always find a place as a fable of virtue regardless of where the canon takes her next.

| ↑1 | Blackwood, B. D. (2010). Isaac Asimov. Critical Survey of Long Fiction, Fourth Edition, 1–4 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Asimov, Isaac. “Robots I Have Known”. Robot Visions. 1990. Originally published in Computers and Automation, 1954 |

| ↑3 | Asimov, Isaac. “Introduction”. The Complete Robot. 1995. |

| ↑4 | Andrew, the titular Bicentennial Man, is also referenced as a mere myth in Robots of Dawn |

| ↑5 | “…there is more than a hint of Robot-as-Menace. Well, if I want to do that once in a while, I can, I suppose. Who’s there to stop me?” – Asimov, Isaac. The Complete Robot. 1995. Quote from “Some Non-Human Robots” and discussion of “…That Thou Art Mindful of Him” in “Two Climaxes”. |