Timothy Zahn first introduced the now-popular character Grand Admiral Thrawn in 1991 as the lead antagonist of his novel Heir to the Empire, in what was then known as the Expanded Universe (referred to now, and hereafter in this article, as Legends). The character was further developed in the next two novels in that trilogy, Dark Force Rising and The Last Command, and though dead following the conclusion of the trilogy, Thrawn also played a significant role in the Hand of Thrawn duology, Specter of the Past and Vision of the Future. A popular character among Legends fans, Thrawn was notably reintroduced into the new canon as an antagonist on the animated series Star Wars Rebels during its third season in 2016. This opened the door for the reintroduction of Thrawn in the literature of the new canon, allowing Zahn to produce two further Thrawn trilogies thus far: one beginning in 2017 and featuring Thrawn, Thrawn: Alliances, and Thrawn: Treason; and Thrawn Ascendancy beginning in 2020, featuring Thrawn Ascendancy: Chaos Rising, Thrawn Ascendency: Greater Good, and Thrawn Ascendancy: Lesser Evil.

However, while ostensibly the same character, the characterization that we get of Thrawn across these texts changes significantly. Even more fascinatingly, it is not a simple matter of a division between Legends and new canon: the characterization of Thrawn in Rebels has more in common with his initial appearance in Heir to the Empire than he does to the version that we see developed in the two canon trilogies. Furthermore, the way that Thrawn is characterized in the Hand of Thrawn duology, and even the way that he is developed in Dark Force Rising and The Last Command, is more nuanced and less straightforwardly villainous than his appearance in Rebels. An analysis of the portrayal of his character and his development across both Legends and the new canon offers us a unique look at the way the new canon has allowed for significant changes in previously established characters, while also calling into question our understanding of this character and what assumptions we might have for him going forward, with the presumed inclusion of him in upcoming live action shows. [1]In order to present a more concise argument here, this article will forgo many examples of direct textual analysis. For an expanded edition of this article featuring close literary analysis of the … Continue reading

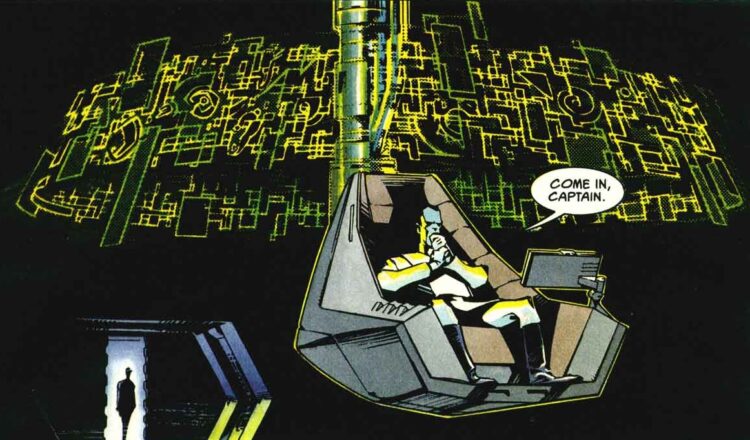

It is key, with all textual versions of Thrawn, to keep in mind the perspective through which our view of his character is filtered. Though none of Zahn’s books rely on a first person narrator (with the exception of some short journal passages as in Lesser Evil’s epilogue), Zahn does frequently focalize his third person narration through characters. And while some of those characters may be immensely likable, when they are Imperial characters (as nearly all whose perspective on Thrawn we are given are), we must consider their own bias in favor of the Empire and often the Grand Admiral himself, as well as the fact that, likable though they may be, they too by nature of being Imperial, are fascists, and their perspective of what is right and good is skewed. To that end, our first introduction to Thrawn is filtered through the perspective of the Imperial Captain Pellaeon, who respects Thrawn as a leader. We are also early on introduced to Thrawn’s respect for art as a mirror of the cultural collective of the species that produces it; a trait which is shared by all literary versions of his character.

However, in Heir to the Empire, despite Pellaeon’s perception that Thrawn is more rational than Emperor Palpatine or Darth Vader, Thrawn’s actions and words are, in fact, decidedly villainous. In chapter one we learn that Thrawn seeks, in his own words, “[t]he complete, total, and utter destruction of the Rebellion.” Notably, Thrawn’s character is the most statically villainous in the first book in the trilogy. In particular, by the time Zahn writes his character in the final book in the trilogy, The Last Command, we see more nuance to Thrawn’s portrayal as a commander, and he is less ruthlessly punitive than he was in Heir, allowing his men to make mistakes without consequences in the third book, that in the first were punished by death. This seems an attempt by Zahn to balance out the earlier ruthlessness, and to position Thrawn as a more balanced and nuanced character, who is, as we are continually told, better and more rational than the Emperor or Vader.

The change in Thrawn’s severity as a commander that we see between Heir to the Empire and The Last Command is not a change that is accountable by any in-universe cause – not that much time passes between the two books, nor does any significant event occur that would explain such a change. We can thus draw the conclusion that this shift comes from Zahn, and how he characterizes Thrawn. Whether this is an unconscious shift on Zahn’s part or an intentional attempt at softening or making Thrawn a more sympathetic character is unknown. However, given the further re-positioning of Thrawn’s motivations that Zahn does in the subsequent Hand of Thrawn duology, it seems likely that the shift to a more nuanced character that we see in The Last Command was intentional.

The Hand of Thrawn duology ex post facto offers us more complex motivations for the villainous actions of Thrawn in the previous trilogy. Though in the Heir to the Empire trilogy it was clear that Thrawn’s goal was the destruction of the New Republic for the glory and power of the Empire, in Vision of the Future, Pellaeon describes Thrawn’s motivations as having been murkier and unknowable. The shift here is indicative of the shift that takes place in this later duology, which seems to attempt to further move Thrawn from the straightforward villain he was in the original Heir trilogy, to the more complexly and even honorably motivated version of his character that we see in the new canon. It attempts to position him as something of an antihero for his people, whose motivations for obtaining power in the Empire are not merely to crush the New Republic for the sake of crushing the Empire’s enemies, but because he wants a strong Empire in order to protect his people, the Chiss. Protecting his people has, this duology claims, always been his ultimate goal.

Thrawn’s motivations are now so drastically altered from Zahn’s original trilogy that the text questions whether Thrawn, should he return, might work with the New Republic rather than the Empire. This is in stark contrast to the goals of New Republic destruction we saw Thrawn profess in Heir to the Empire. It is clear that the more complex version of Thrawn that was being developed in The Last Command is further repositioned in Hand of Thrawn to be an honorably motivated “gray” character, one who is a hero to his people, who is self-sacrificing, and who seeks not to crush and to conquer, but to defend and to uphold. This less villainous and more noble character is the foundation upon which the version of Thrawn we get in the new canon literature is built.

The first version of Thrawn in the new canon literature appears in Thrawn, which came out in 2017, nearly twenty years after the last significant work focused on him, Vision of the Future. As we learned in Vision, from the start of Thrawn we are told that new canon Thrawn’s driving motivation is to protect his people, even if the ruling body of the Chiss disagrees with his methods, even if it means being exiled by them.

As this article earlier emphasized, much of our perspective of Thrawn is filtered through narrative focalized through characters who respect and care about him. In the first new canon trilogy, the majority of our introduction to Thrawn is presented via the perspective of his friend and fellow Imperial, the immensely likable and good natured Eli Vanto. In a sense, Eli himself has a “humanizing” effect on Thrawn’s character. Much of the narrative in Thrawn is filtered through the lens of Eli’s perspective, in which Thrawn becomes a greatly admired figure. Likewise, Thrawn is shown to inspire great loyalty in those who serve under him, and to be seen by them as a source of hope for the future of the Empire.

That being said, at the same time as the new canon’s depiction of Thrawn seems to set him up as a heroic figure, and sympathizes him through the gaze of Eli, there are some echoes of the original, ruthless Thrawn that we saw in Heir to the Empire. There are some details in this initial new canon version of Thrawn that point to him not being a wholly heroic character, or at least to his moral compass being aligned to a different perspective than what we would typically expect from a straightforwardly “good”, or heroic, character. This initial new canon version of Thrawn is less a softer Thrawn than it is a muddied Thrawn – it is a Thrawn with many of the same motivations (at least, as they are presented in the Hand of Thrawn duology) and the same characteristics as Legends Thrawn but filtered through a narrative perspective and presentation that alters our perception of him to a more sympathetic one.

This is not to suggest that the new canon Thrawn is not truly more tempered than the Legends Thrawn, merely that our perception of that tempering is exaggerated by the perspectives through which we see him. It is easy to lose sight of the fact that a character as good-naturedly likable as Eli is himself a member of the Empire, and his view of Thrawn’s actions as a fellow member of the Imperial Navy are colored by this. However, this coloring is a choice by Zahn, as are other ways in which new canon Thrawn is without a doubt less starkly villainous than the original Legends version, as for example, his having increased respect for and reticence toward taking lives.

The Ascendancy novels develop the sympathizing of Thrawn began in the Thrawn trilogy even further by showing examples of him lacking confidence in himself, and even regretting his actions. The trilogy also further develops our knowledge of Thrawn’s relationships with others, as with Ar’alani, who we come to see not only as his fellow Expansionary Defense Fleet officer, but as a close friend of Thrawn’s. [2]This friendship can be seen clearly developed throughout the “Memories” vignettes in Chaos Rising, from their time together at the academy, to their continual service together in the Expansionary … Continue reading This functions in a very similar capacity to the softening of Thrawn’s character as a result of his “friendship” with Eli; though the Ascendancy trilogy takes this softening of Thrawn distinctly further. In the first trilogy, Thrawn’s friendship with Eli, and his caring about him, is implied through Eli’s point of view, and through certain of Thrawn’s actions, but is not explicitly demonstrated or stated. In the Ascendancy books, however, we see numerous explicit examples of Thrawn caring about and feeling emotions for others. Perhaps most notably, in Chaos Rising when he describes the loss of his older sister, clear and poignant sadness from Thrawn is depicted. It adds a significantly complex layer to his character, not only sympathizing him to the reader, but suggesting a further layer to his emotional motivations.

Though it presents him as significantly more complexly sympathetic, the Ascendancy version of Thrawn does not suggest a reading of the character that is entirely different from the one we have gotten previously; his character still has moments of the coldly calculating nature that we have seen from Thrawn all along. The key is that the portrayal of such calculations is more nuanced, and often couched in more noble purpose, not given with no other motivation than because he is a villain.

Seemingly, the version of Thrawn that exists in the new canon is the one whose more complexly developed characterization Zahn introduced in the Hand of Thrawn duology, and one which it could be argued is not in fact a villain at all (outside of, as previously stated, the fact that we must remember that he does work within the fascist regime of the Empire). But we have not yet considered the Thrawn we are presented with in Rebels. The Rebels version of Thrawn appeared before his first new canon literature appearance, with his first appearance on the show set between Thrawn and Thrawn: Alliances. Unlike our perspective of Thrawn in the new canon literature, Thrawn in Rebels is not filtered through any kind of sympathetic perspective, and we are not given any sense of his internal feelings or motivations. He is, overall, a dramatically flatter character. Abstracted from the insights into Thrawn’s character that we get from the new canon literature, Thrawn in Rebels is very much the coldly calculating Grand Admiral that we last saw alive in Legends, and is as ruthlessly villainous as he was at first in Heir to the Empire, and perhaps even more vindictively and pettily cruel.

In perhaps the most jarring dissonance to the understanding of Thrawn’s character that we gain in the Ascendency novels, Rebels Thrawn sneers mockingly at Hera while he speculates that one of the symbols on her Kalikori represents a brother who died young. It seems completely counter to the Thrawn who lost his sister at an extremely young age, and his adopted brother Thrass later on in life, and who we have seen empathize with others who have experienced loss, to use the loss of a brother to inflict emotional pain on another in such a casually heartless way. Likewise jarringly, while all other versions of Thrawn use analysis of the artwork of species in order to better understand them to make strategic and tactical plans, Rebels Thrawn claims he collects art merely as “trophies” or “symbols” that represent some of his greatest adversaries. This completely undercuts what was a significant facet of Thrawn’s abilities as a tactical and strategic commander, and had been shown as a respect for the culture of other species, and makes it a petty and villainous quirk.

This simplification and twisting of these facets of Thrawn into shallowly villainous characterizations underscores the dramatic extent to which Rebels Thrawn is at odds with the in some respects heroic character that he has been developed into in the new canon literature. Rebels Thrawn is a continuation of the straightforward villain we see in Heir to the Empire, without even the slight development or nuance that we see in The Last Command or Hand of Thrawn. He is jarringly different from the Thrawn of either new canon literature trilogy, and most particularly that of the Ascendency trilogy. Thrawn was a straightforwardly villainous character in his initial portrayal in Heir to the Empire. However, later in that trilogy and through Hand of Thrawn we see clear attempts at building out a more nobly motivated character with respect to his ultimate desire to save the Chiss people from a greater threat than that posed by the fascistic regime of the Empire. [3]Interestingly, in Vision of the Future, Thrawn is referred to by one of the Chiss as a “Syndic”, a title, we learn later in the Ascendency books, that is a part of the ruling families structure … Continue reading This raises a potential issue both for future new canon texts and for the assumed upcoming inclusion of Thrawn in future live action Disney+ series: how can Zahn write any books post-Rebels without dealing with the characterization of Thrawn as a stock villain, and will the version of Thrawn that we get in live action be as blatantly and statically villainous as he was in Rebels, or will he be a more nuanced and complexly characterized version as he has been in the new canon literature thus far?

To the first question, we have something of an answer in Zahn’s portrayal of Thrawn in both Thrawn: Alliances and Thrawn: Treason, which are set after Thrawn’s introduction in Rebels. Yes, all versions of Thrawn in the new canon were published after his reintroduction in Rebels. But the Ascendency novels could be explained away by taking place prior to his service in the Empire, as could the first Thrawn novel as the leadup to where we find him in Rebels. However, both Alliances and Treason continue to portray Thrawn post-Rebels introduction as a nuanced character, with honor, who is neither completely loyal to the Empire, nor a mustache-twirling cartoonish characterization of a villain. Seemingly, other than referencing facts about Thrawn’s history that we are given in Rebels, Zahn has completely disregarded Rebels’ return to his initial version of Thrawn as a straightforward stock villain. It seems likely then, that regardless of how Thrawn is portrayed in live action, we may get a subsequent book that either explains away his actions and/or adds layers of complexity to his motivations, either way maintaining our sense of his character as a self-sacrificing genius driven only by a desire to protect his people.

The answer to the second question, regarding the portrayal of Thrawn in live action, is less knowable. Historically, live action versions of Star Wars have disregarded literature whenever it serves to do so. However, we have seen a greater attempt in the new canon era to honor multimodal narratives. That said, with Rebels Thrawn already at odds with new canon literature Thrawn, there is going to be some level of disjointure regardless of which version is honored. Perhaps the way forward lies in a middle ground, in which we see a more villainous Thrawn who claims to have more honorable motivations, even if the other characters (and perhaps even we the audience) are incapable of understanding them. Only time, and further analysis of his character as he continues to be developed and appear in both future literature and televised media, will tell.

| ↑1 | In order to present a more concise argument here, this article will forgo many examples of direct textual analysis. For an expanded edition of this article featuring close literary analysis of the text, please visit Talking Trek Wars. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | This friendship can be seen clearly developed throughout the “Memories” vignettes in Chaos Rising, from their time together at the academy, to their continual service together in the Expansionary Defense Fleet. |

| ↑3 | Interestingly, in Vision of the Future, Thrawn is referred to by one of the Chiss as a “Syndic”, a title, we learn later in the Ascendency books, that is a part of the ruling families structure of the Chiss aristocracy, and while not a title that new canon Thrawn holds, this early reference points to Zahn plotting out a greater background to Thrawn and his people than we were ever given in Legends. |

Everything I’ve been thinking. I crave more of Zahn’s new Thrawn, not the Rebels Thrawn. As a stubborn Legends era fan, I had eschewed all of the new cannon books. I felt like I was somehow betraying the storyline I knew and loved. I’m so glad that I decided to try Zahn’s new Thrawn series. The character is so much deeper and richer. I’m hooked. Next topic: Can Legends books become Cannon? That big gaping hole in the ascendency trilogy (The Vagaari Pirate event which is obliquely referred to over and over but never properly explained.) Legends fans recognized this as a reference to “Outward Bound” The little bit that they do include in “Lesser Evil” about Thrass’s death may even be word for word from the Legends book. If a Legends book does not contradict the Cannon storyline, and supports other material within it, could it become Cannon or maybe just “Pseudo-Cannon”. I am aware that some of the subplots may not agree with Cannon (i.e. Does Disney have plans for Jorj Car’das? Does the presence of Anakin and Obi-Wan conflict with their timeline?). Without reading “Outward Bound” you come to the end of the trilogy wondering where the heck the rest of Thrass’s story went.