The mystique of the buckethead brigade has only grown since Boba Fett’s first appearances in the Holiday Special and The Empire Strikes Back. Their backstory- and the historical cultures upon which it draws- have grown only more convoluted over time, as various authors have accented, overwritten, or ignored the works of previous writers. However, certain historical influences can be sussed out from the turmoil. The Mongols, the early medieval Vikings, and the ancient Celts of Gaul (with a dash of modern Celtic flavor) have all played a role in building Star Wars’ most well-known warrior culture.

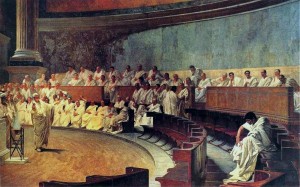

First, a bit of background. Out of universe, the Mandalorians originated with Boba Fett and the background notes established by George Lucas in The Empire Strikes Back– according to Lucas, Fett wore the armor of the Mandalorians, a group of evil warriors exterminated by the Jedi during the Clone Wars. Marvel’s “Star Wars” comic line expanded on the armored menaces, giving them a home planet (Mandalore, later rendered as ”Manda’yaim” in Mando’a) and establishing that their warrior culture still existed post-Clone Wars. The Clone Wars adventures of the Mandalorians were explained (and were later brilliantly retconned by Abel Peña in his “History of the Mandalorians” article, creating Spar a.k.a. Mand’alor Gayiyli, or Mandalore the Resurrector), with the Mandalorians eventually aiding the nascent Republic. While the Marvel era was left somewhat to the wayside in the Bantam-era EU, the Mandalorians continued to be utilized by various authors. In particular, Tom Veitch and Kevin J. Anderson laid much of the groundwork for Mandalorian culture in Tales of the Jedi, depicting the early Taung as nomadic warriors and raiders from the Outer Rim. The Knights of the Old Republic mini-franchise further expounded upon early Mandalorian warrior culture, positioning them as something of a cultural bogeyman to the Roman-inspired Galactic Republic. Later, Karen Traviss added her own substantial interpretations to Mandalorian culture, bringing in further Celtic motifs and developing the framework for a Mandalorian language.

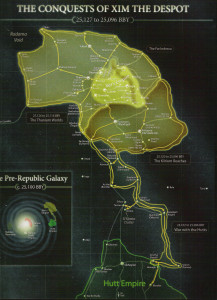

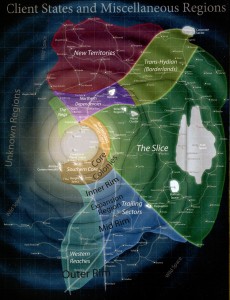

Generally speaking, the Mandalorians resemble various nomadic groups throughout history. They were driven from their original homeworld- Coruscant- and travelled from world to world, settling on planets such as Roon, Shogun, Basilisk, and Ordo before settling down in the Mandalore system circa 7000 BBY. One element in particular links them to the Mongols of the late Medieval period- their willingness and ability to effectively assimilate conquered groups and cultures into their ranks, whether using their technology, taking advantage of their knowledge of trade routes, or simply assimilating them into their ranks. The Mongols under Ghenghis Khan and his successors were able to utilize Chinese knowledge of gunpowder and siege equipment to conduct their military campaigns in Khwarizm, Mesopotamia, India, and the Russian steppes. They were further able to integrate far-flung regions into their (only briefly unified) empire, respecting freedom of religion, expanding trade routes, and providing military protection to the conquered (assuming one survived the initial military assault, naturally). Similarly, the Mandalorians were almost fanatical about incorporating groups who had survived their conquests. Upon settling in the Mandalore system, the ancient Taung (note: the name “Taung” comes from a young Australopithecus skull discovered in Taung, South Africa in 1924) immediately made war upon the native Mandallian Giants, who survived the buckethead onslaught and were subsequently incorporated into the Mandalorian war machine. Later in history, as the Taung themselves were gradually worn down by constant warfare, the Mandalorian culture became incredibly multiethnic, incorporating species as diverse as Rodians, Twi’leks, Herglics, and humans- humans would come to be the dominant species within the Mandalorian culture.

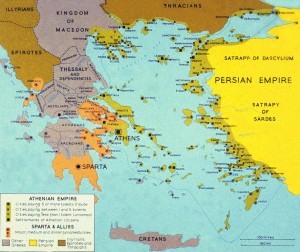

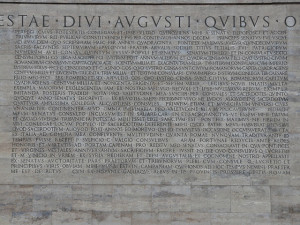

Perhaps one of the most inspired elements of Karen Traviss’s interpretation of Mandalorian history and culture was her utilization of general Celtic elements to color her spec-ops warriors. The Gauls- a Celtic culture that inhabited parts of modern-day France (the Celts themselves settled as far afield as the British Isles, Northern Italy [Gallia Cisalpina], Modern Spain, parts of the Balkans, and even central Turkey [the region known as Galatia draws its name from its former Celtic inhabitants]) were something of a cultural bogeyman to the Roman Republic, similar to the role played by the Persians in Hellenic culture and the Mandalorians in the Galactic Republic. The La Tene culture- a Gallic subculture located in Northern Italy- even sacked the city of Rome itself in 390 BCE, the last time that the city would be breached by a foreign enemy until the Sack of Rome in 410 CE. Not ones to be upstaged by their real-world inspirations, the Mandalorians participated in several battles at Coruscant, such as Ulic Qel-Droma’s raid during the Great Sith War and the sack of Coruscant at the end of the Great Galactic War under the command of Darth Malgus. Interestingly, the Romans were not absolutely averse to friendly interactions with the Gauls, despite their various wars with them- the late Roman Republic and early Empire adopted Gallic-style helmets, and often preferred to hire Gallic mercenaries rather than utilize their own native cavalry. Similarly, the Mandalorians inspired the armor of the Grand Army of the Republic, and the GAR itself was partially trained by (and cloned from) Mandalorian commandos.

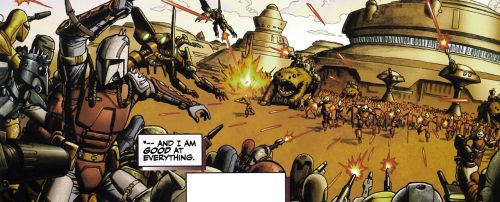

One last historical inspiration for Mandalorians can be found a bit farther north in Europe – the Vikings of Scandinavia. Much like the Mandalorians, the Vikings were perceived as a highly militaristic culture, the scourge of Western Europe. While recent archaeological evidence suggests that the Vikings also engaged in a great deal of long-distance trade, transmitting goods and ideas along the seas of Western Europe and the Volga and Dniepr Rivers, their reputation as successful raiders is nonetheless well-deserved. They were able to conduct long-distance raids through the use of their longships- vessels that could travel rivers, coastlines, and the open sea. The ancient Mandalorians were able to utilize their Basilisk War Droid to similar tactical effect, popping out of hyperspace astride fighter-sized technological terrors that could operate in deep space and in an atmosphere. While they at times menaced the Eastern Roman Empire, Viking mercenaries were eventually hired to form the Varangian Guard, an elite unit in the Eastern Roman military. By the 12th century, the makeup of the Varangian Guard had largely shifted from soldiers of Norse descent to men from the British Isles. While they were an almost existential menace in the Republic’s psyche, the Mandalorians were perfectly willing to work for Coruscant when it suited them. They were hired by both sides during the New Sith Wars, and as mentioned earlier trained the Republic’s army prior to the Clone Wars (which did not preclude the Mandalorians from fighting against those very clones- Mandalore the Resurrector’s 212 Supercommandos were almost entirely wiped out in an engagement with the Galactic Marines on Norval II). The aforementioned gradual shift in Mandalorian identity from a single species to a multi-species culture is also reminiscent in the make-up of the Varangian Guard.

While almost certainly unintentional, the way in which these historical cultures have been interpreted, reinterpreted, and rewritten mirrors the rather haphazard nature of Mandalorian continuity. The Vikings, who for years were seen as little more than raiders, have in recent decades been re-evaluated for their impact on trade throughout Europe and the Middle East. The Mongols have experienced a similar renaissance in Western historiography, in recognition of how their conquests aided in the exchange of scientific, social, economic, and military ideas between Europe and eastern Asia, as well as their ability to integrate a far-flung heterogeneous empire. The ancient Celts, of course, have been utilized as nationalistic symbols by their descendants in the British Isles and France- although the modern nation of France is more directly connected to the Franks than the Gauls. In a similar vein, the Mandalorians have gone from simple elite villains to a dynamic warrior culture who occasionally even get to play the hero.

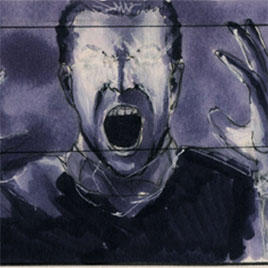

One interpretation of Daoism is that it is utterly passive, and that Daoists should make no effort to change the world. This interpretation is indeed a technically valid interpretation; the founder of Daoism, Lao-tzu, advocated severing oneself from society and becoming a hermit. However, when one considers the idea of Tian—namely, that heaven is on Earth and that it is inherently a process rather than a state—a completely opposing interpretation emerges. If heaven is a process, then it is a process that mankind must contribute to. In other words, man must take the understanding of the universe which it has gathered from the Dao and utilize this to make the world a better place—to create heaven on earth. Following one’s Li lines means applying the principle of Wei Wu Wei—active non-action—in a decidedly pro-active form. When Ganner sacrifices himself in Traitor, he is following his Li line to its fullest extent. His action—playing Horatio at the Gates in a manner that puts Gandalf the Gray to shame—allows Jacen to escape and follow his own Li lines, which culminate in his finding a peaceful resolution to the bloodiest war in galactic history.

One interpretation of Daoism is that it is utterly passive, and that Daoists should make no effort to change the world. This interpretation is indeed a technically valid interpretation; the founder of Daoism, Lao-tzu, advocated severing oneself from society and becoming a hermit. However, when one considers the idea of Tian—namely, that heaven is on Earth and that it is inherently a process rather than a state—a completely opposing interpretation emerges. If heaven is a process, then it is a process that mankind must contribute to. In other words, man must take the understanding of the universe which it has gathered from the Dao and utilize this to make the world a better place—to create heaven on earth. Following one’s Li lines means applying the principle of Wei Wu Wei—active non-action—in a decidedly pro-active form. When Ganner sacrifices himself in Traitor, he is following his Li line to its fullest extent. His action—playing Horatio at the Gates in a manner that puts Gandalf the Gray to shame—allows Jacen to escape and follow his own Li lines, which culminate in his finding a peaceful resolution to the bloodiest war in galactic history.

My understanding of Daoism is based upon, of all things, the Star Wars mythos. In particular, I can cite the New Jedi Order novel Traitor as being the key to my understanding of Daoist teachings; the author has a much more thorough grasp of the Force’s philosophical roots than George Lucas himself could ever dream of. The novel follows Jacen Solo’s journey of self-discovery while in captivity. For those who have not read the New Jedi Order, Jacen Solo is the oldest son of Han Solo and Leia Organa Solo, and twin brother to Jaina Solo. For those readers who haven’t read the New Jedi Order (and are likely unaware of the fan debates surrounding it), In the novel Traitor, Jacen Solo is held captive by the invading Yuuzhan Vong in the aftermath of the Jedi Strike Team’s assault on a Vong bioweapon facility, and the resulting death of Anakin Solo. Jacen is taught by the enigmatic Jedi known as Vergere, an unorthodox figure who has since been smeared as a “Sith”. But the epithet “Sith” cannot be further from the truth of Vergere—who herself does not exactly consider the spoken word, the name, or indeed language itself, to contain more than a glimmer of the truth. Like a good Daoist, Vergere recognizes that any truth which can simply be described, quantified, or categorized by words isn’t really a truth at all. Rather than being a product of Sith teachings, Jacen’s revelations teach him to love the universe for all of its faults, find his inner strengths, and use these to further the cause of “Tian”—the process of heaven on earth.

My understanding of Daoism is based upon, of all things, the Star Wars mythos. In particular, I can cite the New Jedi Order novel Traitor as being the key to my understanding of Daoist teachings; the author has a much more thorough grasp of the Force’s philosophical roots than George Lucas himself could ever dream of. The novel follows Jacen Solo’s journey of self-discovery while in captivity. For those who have not read the New Jedi Order, Jacen Solo is the oldest son of Han Solo and Leia Organa Solo, and twin brother to Jaina Solo. For those readers who haven’t read the New Jedi Order (and are likely unaware of the fan debates surrounding it), In the novel Traitor, Jacen Solo is held captive by the invading Yuuzhan Vong in the aftermath of the Jedi Strike Team’s assault on a Vong bioweapon facility, and the resulting death of Anakin Solo. Jacen is taught by the enigmatic Jedi known as Vergere, an unorthodox figure who has since been smeared as a “Sith”. But the epithet “Sith” cannot be further from the truth of Vergere—who herself does not exactly consider the spoken word, the name, or indeed language itself, to contain more than a glimmer of the truth. Like a good Daoist, Vergere recognizes that any truth which can simply be described, quantified, or categorized by words isn’t really a truth at all. Rather than being a product of Sith teachings, Jacen’s revelations teach him to love the universe for all of its faults, find his inner strengths, and use these to further the cause of “Tian”—the process of heaven on earth.