First, a disclaimer: while this piece won’t be getting into major plot details from Bloodline (since we haven’t read it yet), we will be dealing directly with information from the three-chapter excerpt that was released late last week by instaFreebie [1]Editor’s note–this piece mistakenly credited the release to the Playcrafting newsletter in its original form regarding the political context and background of the sequel era. If you deem that to be spoilery, proceed at your own discretion.

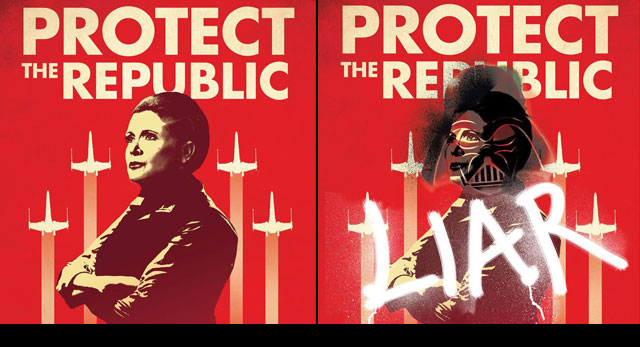

Mike: So Jay, you and I have spoken on and off about Leia’s founding of the Resistance as a difficult move to judge from our perspective here in the real world—on the one hand, we know the First Order is a serious threat, but in-universe, it’s very easy to see how she’d come across to the post-Endor generation as an old soldier refusing to accept peace, or worse, as a warmonger. At the beginning of Bloodline we learn that after a couple decades the New Republic senate has polarized into two factions: the Centrists, who favor a stronger leadership role for the Republic and a more aggressive military, and the Populists, who prefer more power and autonomy for individual planets. While at first glance it seems sensible that Leia would be part of the Populist faction, it’s especially interesting considering that she’s on the verge of starting her own army.

What first struck me about this backdrop, though, is how believable it felt—at least to someone used to American politics, which are nominally divided into “federal” people and “state” people. Something you’ve brought up here multiple times is the danger of haphazardly translating contemporary political issues into Star Wars’ fantastical setting, when they don’t really apply. Not only does Centrists/Populists feel to me like an artful distillation of real political divisions, it feels like a very appropriate division for the GFFA to have at this point, when so many of its members would be ex-Imperials and ex-Separatists alike. It takes the sort of generic sense of “corruption” we already knew was coming (and which appeared to varying degrees of success in the Expanded Universe) and grounds it in the known history of the galaxy—just like I’ve been hoping for all along. Did you get a similar real-world feeling from it?

Jay: Almost immediately — and it was a vibe that reinforced the sense I got when we got the first teaser summaries, too. When I first heard of the Centrists and the Populists, I immediately thought of the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans from late 18th and early 19th century American politics. It was a gratifying comparison, because the First Party System is actually one of my favorite periods of history (and that was well before it became the centerpiece of a certain very popular musical that I must find a way to see). I’ve been harsh on transplanting contemporary politics into Star Wars, especially when it comes to deciding who gets to be the hero and who gets to be the villain. But I’ve always said that history is different — we’re looking from a different perspective, and the historical approach is good for exploring ideas because we can get a sense of what historical politics mean in context, where they went, etc with a sort of detachment we don’t have with contemporary politics. George Lucas himself, after all, based the Star Wars films in part on the fall of the Roman Republic, the rise of Napoleon, the Third Reich, Richard Nixon’s crony politics, and the American Revolutionary War against the British Empire.

So Gray’s echoing of post-founding American politics is not only in keeping with all that, but it echoes perfectly. Here we have a post-revolutionary New Republic. In fact, the excerpt shows how nice of a fit it is because we learn that the position of chancellor was pretty ineffectual and the New Republic actually lacked an executive. That brings to mind the inefficiencies of the American post-revolutionary Articles of Confederation, where federalists and anti-federalists (predecessors of the Federalist and Democratic-Republican/Jeffersonian parties, though not entirely overlapping) debated the merits of a national government and an “energetic” executive. Given that we know that there’s some First Senator position that the Centrists pose, the analogies write themselves. Important too is not whether or not the issues are an exact fit, or whether the Populists fit closer with the anti-federalists or the Jeffersonians — or even whether it’s a perfect fit (for example, most of the officers and leaders of the Revolutionary War tended to be Federalists because the war made them recognize the need for unity, while Leia is clearly a Populist here because of her fears of central authority).

It’s not a perfect fit and it’s not supposed to be, because Gray isn’t giving us a retelling of American history in space. She’s echoing familiar ideas because this immediately helps contextualize the readers. We may not know what happened in the past twenty odd years of galactic politics, but we’ve already oriented ourselves because we understand the arguments and feel of the debate. And if we’re not Americans, the debate over central vs. delegated authority will echo in other political contexts too — the Legislative Assembly and the Directory of the French Revolution, or the diffuse post-war powers of the German chancellor. If we really want to be fun, we can even give it a contemporary cast that I don’t think is intended — think of the EU (that thing in Brussels, not the other one!) and discussions over supranational authority in the Council vs. the electoral authority of the Parliament, or the statecraft-y tinge of the Ministers. Or what about the UN and the principle of sovereign equality of states vs. the Right to Protect principle — letter versus spirit of the law, anyone?

But I’m liable to get carried away with all the comparisons. The point is that there’s a certain familiarity in the Centrist vs. Populist struggle that exists to make the stakes and issues clearer, without need for exposition or to spell them all out. When one or the other makes a point or a complaint, the reader knows exactly what’s going on.

Mike: There’s also been a lot of early talk about the Imperial sympathizer Ramsolm Casterfo, and his echoes of certain, ah, participants in this conversation. One thing I noted from his scenes is that he and I are almost the same age—and as such, I actually found myself very much understanding his point of view. I don’t get the appeal of collecting war artifacts (of any kind), but as someone who believes in at least the ideal version of a strong central government, Casterfo’s perspective that the Empire would’ve been great if it wasn’t for that pesky Emperor was one that I have to admit felt reasonable. I especially appreciated that he wasn’t just a fop who got off on the pageantry of the Empire; he seemed to have real principles behind his opinions—he’s the embodiment of the time-honored “well so-and-so was a bad guy but he made the trains run on time” perspective. If someone can grow up (apparently) within New Republic society to be like him, well, I can only imagine the kind of things teenage Hux was being taught out in the Unknown Regions.

Mike: There’s also been a lot of early talk about the Imperial sympathizer Ramsolm Casterfo, and his echoes of certain, ah, participants in this conversation. One thing I noted from his scenes is that he and I are almost the same age—and as such, I actually found myself very much understanding his point of view. I don’t get the appeal of collecting war artifacts (of any kind), but as someone who believes in at least the ideal version of a strong central government, Casterfo’s perspective that the Empire would’ve been great if it wasn’t for that pesky Emperor was one that I have to admit felt reasonable. I especially appreciated that he wasn’t just a fop who got off on the pageantry of the Empire; he seemed to have real principles behind his opinions—he’s the embodiment of the time-honored “well so-and-so was a bad guy but he made the trains run on time” perspective. If someone can grow up (apparently) within New Republic society to be like him, well, I can only imagine the kind of things teenage Hux was being taught out in the Unknown Regions.

My favorite little detail about him, though, is that he’s not a haughty nobleman from some storied Old Republic family—he’s from a minor manufacturing planet that was hit hard by the war and yearns to appear more important than it currently is. In other words, he’s less Tagge than Tarkin. You’ve always said that Tarkin represents everything that was wrong with the Empire, but I suspect you’re much fonder of Casterfo—how do you square that circle?

Jay: Oh, you just had to mention his background, didn’t you? That’s actually the bit that distresses me quite the most about him — I’ve been told for a while now that I’d like Casterfo and that he sounds similar to me but the fact that he’s actually a bumpkin leaves me pained. I’ll also add that there’s nothing wrong with fops who enjoy pageantry, dangit. I think it would’ve been very interesting had he been a Core World senator, perhaps even from Coruscant, because it would’ve shown that the Empire and the Old Republic weren’t that far apart — and it works well with the leveling notion of the New Republic, with the democratization and the moving away from the pomp that characterized both the Galactic Republic and the Galactic Empire. That Coruscant-led culture is still there, and I’d have liked for Casterfo to represent that.

But as much as it loses in the contrast between the old and the new, I do agree that it makes his perspective interesting. His Inner Rim world is not one that really benefits from the Empire’s Core-centric preferences. The world would not have been coddled and favored. Casterfo, too, isn’t arguing to regain some lost privileges. Rather, he notes that his world was probably better off under the Empire because of the way things were run. It makes for a more compelling argument — it’s all well and good for someone to say that the Empire was better because you and yours got privileges they’ve lost, but it’s another matter to say everyone was better off under a well-run machine.

His conversation with Leia is interesting in that regard. Casterfo is willing to differentiate the Galactic Empire as a system of government from its reality as one ushered in by a despot. He’d probably like the Empire that Rae Sloane and Ciena Ree thought they were serving, the entity that the Empire tried to convince everyone it actually was. His thesis is that if the Empire actually lived up to its promise, wouldn’t it have been great? Leia sees the Imperial system as irredeemably rotten — that not only was the Empire awful, but any attempt to centralize the Republic is just as awful. She is unwilling to separate the Empire’s actions from its system.

![Rae_Sloane_Orientation[1]](http://eleven-thirtyeight.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Rae_Sloane_Orientation1.png) It’s an interesting contrast, and I hope we see more of their debates. The argument was cut short before Leia had a chance to deliver some more substantial arguments — e.g. the issue of accountability and what happens when a ruler isn’t benevolent — but I’m sure we’ll get to it. What I got out of the discussion was that Casterfo did have a point, and one that makes him interesting instead of a caricature. I like that — it would’ve been very easy to just go with the unreconstructed Imperial idea, and Gray didn’t do that.

It’s an interesting contrast, and I hope we see more of their debates. The argument was cut short before Leia had a chance to deliver some more substantial arguments — e.g. the issue of accountability and what happens when a ruler isn’t benevolent — but I’m sure we’ll get to it. What I got out of the discussion was that Casterfo did have a point, and one that makes him interesting instead of a caricature. I like that — it would’ve been very easy to just go with the unreconstructed Imperial idea, and Gray didn’t do that.

As for the contrast with Tarkin, well that’s an easy one. While both Tarkin and Casterfo are Rimmers (Tarkin moreso) who imitate Core World accents, Casterfo seems (so far) to be about more than just survival of the fittest. He actually believes in the Empire as a force for good, while Tarkin had developed an ideology that’s essentially the secular version of Sith ideology: ruthlessness is its own end. I still wish Casterfo would be the public-spirited ancient Core World type, but I don’t think that necessarily mean he’s Tarkin. Also, Casterfo does have a satisfying preference for finery. That’s important.

Obviously.

Mike: I do find myself hoping he sticks around after the events of the book, and perhaps even survives the destruction of Hosnian Prime somehow—it’s interesting to think about how he’d react to such savage actions on the part of other neo-Imperials. Claudia Gray certainly knows how to craft compelling antagonists.

There’s another thought I’ve been toying with lately that the excerpt shined some new light on—sound in space and faster-than-light travel notwithstanding, one of the least realistic elements of the Star Wars universe, in my opinion, is the idea that the Old Republic was at one point a genuine utopia. There were some sort of conflicts with the Sith in ancient times, and then, for somewhere between several centuries and several millennia, there was a period of Ideal Government: no great wars, prosperity, fairness, and so on. The Sith eventually work their way into this system and corrupt it from within, a process that was well under way by the time The Phantom Menace kicks off so that we never really get to see just how ideal things really were—but to hear the Journal of the Whills describe it, they were pretty nice.

If you accept this premise (and I concede that it’s reasonable not to), then to my mind there has to be something fundamental about the populace of this galaxy that makes them, well, better than us. Maybe it’s the best parts of so many different races and cultures rubbing of on each other over time, or maybe it’s the Force subtlely, literally, working its magic, but there are things they seem to pull off that we here on Earth just couldn’t.

Chief among these, and this is where Bloodline comes in, is the prevalence (and seeming effectiveness) of child rulers and representatives. Leia and Padmé would be noteworthy enough on their own, I think, but according to Leia in the excerpt, there are “many” in the New Republic senate who weren’t yet born when the Battle of Endor took place twenty-four years earlier. To join the government at fourteen, as both Leia and her mother did, is presented as challenging but not all that unusual, which suggests to me a marrying of the inherent idealism of youth with what has to be a far more efficient and balanced educational system than any on Earth—for the upper classes of Naboo and Alderaan at least, but again, this may in fact be quite common.

The Empire does arrive right on schedule, of course (there’s those trains again), but one of the biggest changes from the Expanded Universe to the new canon is that once Palpatine is dead, the war to defeat the Empire becomes a popular uprising as much as a naval operation. Only a generation or so after happily handing over absolute power to a tyrant, the galaxy rises up and tears his entire system down in the space of a year. It may cherry-pick elements from our history, but on the whole this is just not a thing that could really happen, I don’t think. That doesn’t make it bad—Star Wars is a fairy tale, after all—but it casts the sequels in a very interesting light. What was the real fluke here, the Old Republic or the Empire? Am I just taking the rosy “Republic of legend” stuff too literally?

Jay: Maybe I’m an optimistic believer in fairy tales, but I don’t believe that the Republic of legend necessarily makes people better than us. Of course, part of the thing about Camelot fables is that they’re always rosy and not meant to be taken literally: that’s part of the point. The Old Republic surely did have its problems, but those were problems that were obscured while everything was working right. They were problems that didn’t get revealed until things started creaking apart. But from the point of view of the Imperial period, just as in the point of view of say — the dark ages — the past seems full of light and wonder and amazement. It’s part of that fairy tale element of it, and it’s part of why there’s great risk in exploring the Old Republic setting in narrative because you risk getting too close to that grand painting and seeing all the painted over strokes and mistakes.

But even taking aside that observation about the nature of wistful nostalgia, I do think it’s impossible to deny that the Old Republic was a different, more optimistic time. Even during its later days — that was what Lucas was going for, particularly with Naboo. There was a comment Leia made in Shattered Empire that’s very instructive: she said something like Naboo represented the best of the Old Republic. Though Naboo isn’t a Core World or a Founder or anything like that, I think that’s a pretty accurate observation of how Lucas intended Naboo to function in the PT. Naboo was that idealistic world that embodied the true spirit of the Old Republic that was lost on Coruscant by then. They were idealistic, with their elective monarchy, child rulers, and faith in the people’s choices. They were artful, serene, peaceful, contemplative. Padmé had a childlike innocence and faith in the Republic’s anti-slavery laws — not just because she was young, but that was the society she was raised in. The Queen’s advisors all expect the Senate and Jedi negotiators to be able to do something, because that’s what they do. But then Padmé gets to Coruscant, and learns from Palpatine what’s really happened to the Senate in recent years.

That’s it — that’s your primer — the Old Republic that was (refined, artistic, democratic, peaceful) and the Old Republic in its dying years (corrupt, sluggish, unconcerned). So the Empire comes along and sweeps away the corruption and inefficiencies through the fires of war, only to replace them with more centralized treatment. The Core is still where all the corruption occurs, and is still where all the benefits go but there’s that narrative that the Empire is cleaning up the Rim that the Republic just left there. The illusion of the Republic’s corruption is dealt with, while the reality stays. And that’s perhaps why the New Republic is like, let’s just get rid of the whole thing. Let’s start over. And the first step, we’re not bound to Coruscant — there’s too much baggage there.

It’s sad for me, since Coruscant will always be my favorite. But it makes sense — the New Republic is trying to inaugurate a new optimism. The excerpt suggests though that the NR is overly concerned with style over substance, and it really repeats the same mistakes of the Empire in that way: it makes a big show of getting rid of what the previous governments did wrong, but it doesn’t actually do it.

As for the Empire getting torn down so quickly, I wonder if it’s a function of the shorter timeline in light of the prequels. The EU was operating on the assumption that the Empire was around for a while, at least a couple of generations. Few were around who remembered the Old Republic — they were all in their sixties. It was institutional, and it was the government. The NR had to start from scratch, and realized that it couldn’t — it only really started achieving rapid success when it took Coruscant and absorbed the Imperial ruling bureaucracy, and even then worlds stuck with the Empire for years and years. In contrast, the NEU is going with the “regime change” model — the NR and Rebels aren’t an external force fighting the galactic government. They’re internal revolutionaries. They rise up in the hinterlands, make a stab for the governing apparatus of the galaxy while the government is in utter disarray, and after a series of spectacular victories, are handed the reins of power. The Empire falls as quickly as it came into being: circumstantially and the product of a change in government.

Mike: So in light of all this, are you still optimistic that the New Republic is actually an improvement upon the late Old Republic? I mean, obviously we know things don’t go well over the next several years while the First Order slowly consolidates its power, but is the conflict as presented in Bloodline a fatal flaw or a bump in the road? In other words, pretend there is no First Order and the NR is left to its own devices—do its partisan problems feel solvable, or is this more of an “Articles of Confederation” phase, where they’d be better off scrapping the whole thing and starting over?

Jay: Heh. Well, obviously the New Republic has some issues. Partisan gridlock, but that’s just symptomatic — the NR’s structural issues have caused these parties to take starkly opposing viewpoints on how these issues should be solved. It’s not a healthy political system. It’s too early to judge whether it’s an improvement on the Old Republic — or whether it should have followed the Legends NR in trying to imitate the Old Republic (to the extent the EU knew about it at the time). But it’s clearly broken.

But here’s the thing. It has the luxury to be broken. The New Republic won the war. It established peace. It unified the galaxy. That’s no small thing. I can’t really say “hah! They failed, the Empire had it right all along!” That was easier to say with the Legends New Republic, which did end up failing (though an extragalactic invasion, not unlike the First Order, was the immediate culprit). Absent external circumstances, I do think that the New Republic is deeply sick, but not a failure.

Perhaps Casterfo is right, and a stern hand at the helm is what’s necessary. Perhaps Leia is right, and a focus on duty and service like in the days of the Imperial Senate (on its good days) are what’s important. My personal jury’s still out on that one, but I’m pretty much still leaning towards Leia at this point (despite my fondness for Imperial pomp) — but I don’t think the fact that there’s disagreement means the New Republic hasn’t worked.

I think its extreme egalitarianism is silly. I think it went too far. I think that Casterfo and Leia both have good ideas (and that Leia’s idea of bipartisan unity is what’s needed — I don’t think she does a good job in meeting the Centrists half way, but it’s still a good idea). I think it can be saved. But I don’t think it failed. If anything, that commemorative ceremony on Hosnian Prime that opens up the book shows that.

As far as I know so far in three chapters, the New Republic won the war, brought peace, and therefore bought itself the luxury to be politically dysfunctional twenty-four years after Endor. It’s not perfect, but it’s a work in progress. So long as people keep trying, it’s worth saving. That may end up requiring drastic changes — we figured in Aftermath that Mothma’s crazy idealism wouldn’t last, and we’re seeing that come to fruition now. But I think if not for the First Order on the horizon, which cut all of this short, it would’ve been solvable.

| ↑1 | Editor’s note–this piece mistakenly credited the release to the Playcrafting newsletter in its original form |

|---|

re: Casterfo and the dstruction of Hosnian Prime

It would be quite interesting if he did survive and then turn on the First Order for being so incredibly excessive, the same kind of excess that lay behind the Death Star and which ultimately destroyed the Empire.

On a general note, you two might well talk me into buying this despite my ambivalence for the new late post-ROTJ era.

That would be nice. It would certainly make the Casterfo comparisons even more appropriate :p

I suspect the political comparisons are going to run and run. For instance, if Casterfo is practically denouncing the Emperor while praising the Imperial system, that takes him close to Khrushchev’s denunciation of Stalin.

(Need to actually have a read of those 3 chapters now.)

Well, he’s not actually an Imperial though — he’s a young New Republic senator who was too young to fight in the war. It’s a little bit different from the example of a more moderate ruler rejecting the excesses of his predecessor.

OK, found the book in Waterstones, had a flick through – the verdict?

That fucker and the Senate deserve to burn.

Very good article. One of the strengths of the new canon is that we have learned that though the Rebellion was a bigger threat to the Empire and that it started with a lot of minor cells (like the Rebels one in Lothal) we have also learned there was people in the Empire that were not aware of the Sith ruling the galaxy but thought the order brought by the Empire was good. After reading those three chapters I am really looking forward to read the whole book next week and find out what happens next.

I like the way Claudia Gray is developing Casterfo – and based on her mental casting – Tom Hiddleston – now I have a image in my head for him. Hope he survives the Starkiller destruction of Hosnian Prime.