The Star Wars universe, despite originally depicting a very Manichean struggle between good and evil, has become in the decades since the original movie a very morally nuanced place. I’ve mentioned before that if I look at the current status of the franchise, I’m tempted to consider Star Wars to be more of an anti-war story than a war one, but that’s a debate that we’ve had on this website very recently. Personally, I feel that although the original trilogy no doubt romanticized armed insurgency, George Lucas’s point of view on war and violence had evolved and become considerably more pacifist by the time the prequels and The Clone Wars rolled in.

Behind the curtain of space fantasy, George Lucas told the audience about things like false flag operations, the military-industrial complex, and factionalism in insurgencies. The heroes of the story, the Jedi, lose because they get involved in war. War itself is bad. If we look at the totality of the material that Lucas himself produced under the banner of Star Wars, behind all of the heroics and the swashbuckling, it sure appears to tell us that war sucks. But is there a way to add a bit more nuance to this message without negating it?

Enter Saw Gerrera: the only Rogue One character appearing on the big screen for the first time while remaining an original Lucas creation, having been originally developed for the never-filmed Star Wars: Underworld TV project and first seen in animated form in The Clone Wars, Saw Gerrera is played by Academy Award winner Forest Whitaker and is set to make a big splash in the galaxy. The Databank describes him as “a battered veteran of the Clone Wars as well as the ongoing rebellion against the Empire, [who] leads a band of Rebel extremists. Saw has lost much in his decades of combat, but occasional flashes of the charismatic and caring man he once was shine through his calloused exterior.” Lucasfilm president Kathleen Kennedy told Entertainment Weekly that Saw Gerrera is “on the fringe of the Rebel Alliance. Even [they] are a little concerned about him. […] He’s off on his own” and Whitaker says that “he really believes that what he has done is right. He understands that […] worlds could be destroyed if he doesn’t succeed. And he’s one of the only people who will do everything to make sure the Imperial forces don’t.” Saw Gerrera is set to have been of the original architects of the Rebel Alliance, but one who is not in good terms with Mothma, Organa, and the rest. He has his own faction of extremists (called “partisans” in Bloodline) and he appears to be fighting his own fight against the Empire. And that is something that history tells us has happened over and over.

Because, for all the talk about his filmmaking influences, Lucas has also drawn some heavy inspiration from human history. The story of Gerrera’s rebel faction reminds us of diverse guerrilla movements throughout history, being depicted as an insurgency armed by the very government it’s rising up against (like, among many examples, the Afghan Mujahideen) and showing a side of the Rebel Alliance that we had only seen before in a very small way: that the Alliance is not a monolithic group but made up of different factions with their own agendas and their own reasons for rising against the Empire, reasons that sometimes might be at odds with each other. Because in the real world factionalism is a big factor in most armed revolutions and can sometimes decide the whole course of the war.

After the French Revolution, members of Legislative Assembly were split into different political clubs, from the moderate Girondists to the reactionary Feuillants and the radical Jacobins, the latter being the party responsible for Robespierre’s Reign of Terror. The split of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party into the Bolshevik and Menshevik factions was carried into the Russian Revolution of 1917, with Mensheviks being outlawed in 1921 after the Kronstadt rebellion and Lenin being so worried about factionalism that it became the central topic of the 10th Congress of the Russian Communist Party. The Cuban Revolution involved several dissatisfied factions rising against Batista, including groups as politically opposed as the communist 26th of July Movement led by the Castro brothers and Ernesto “Che” Guevara and the fervently anti-communist Student Revolutionary Directorate. During the American Revolution, factionalism and regionalism walked hand by hand, with trouble brewing between the states, like New York and New Hampshire or Pennsylvania and Virginia (and yes, we could easily see hints of this in any possible tension between Gerrera’s Outer Rim-spawned forces and Mothma and Organa’s Core Worlds group).

But, perhaps accidentally, perhaps on purpose, the closest real-life equivalent to Saw Gerrera and his partisans can be found in the Spanish Civil War, in Buenaventura Durruti and his infamous Column. The Durruti Column was the largest anarchist military unit during the war; originally a ragtag group of militias formed in Barcelona when several far-left militants saw that the government of the Republic had done nothing to protect the city from Franco’s forces and armed themselves with stolen weapons, it became one of the most recognized military units during the early war, getting an almost mythical status. Buenaventura Durruti (14 July 1896 – 20 November 1936), their leader, was a hardline activist more than familiar with violence, having been involved in the shooting of the Archbishop of Saragossa, in a failed attack on military barracks after short-lived dictator Miguel Primo de Rivera seized power, and even in bank robberies in Chile and Argentina during his decade of exile from Spain.

But, perhaps accidentally, perhaps on purpose, the closest real-life equivalent to Saw Gerrera and his partisans can be found in the Spanish Civil War, in Buenaventura Durruti and his infamous Column. The Durruti Column was the largest anarchist military unit during the war; originally a ragtag group of militias formed in Barcelona when several far-left militants saw that the government of the Republic had done nothing to protect the city from Franco’s forces and armed themselves with stolen weapons, it became one of the most recognized military units during the early war, getting an almost mythical status. Buenaventura Durruti (14 July 1896 – 20 November 1936), their leader, was a hardline activist more than familiar with violence, having been involved in the shooting of the Archbishop of Saragossa, in a failed attack on military barracks after short-lived dictator Miguel Primo de Rivera seized power, and even in bank robberies in Chile and Argentina during his decade of exile from Spain.

When Madrid was threatened by Franco’s armies in late 1936, the Durruti Column marched down from Barcelona to defend the city, rallying people to its banner on the way and multiplying its original size by a factor of three. Durruti himself died during the campaign, and the following year the Column joined the Republican Army, becoming part of the 26th Division and continuing to fight, this time alongside the Republic loyalists. It’s tremendously easy to draw parallels with what we know of Gerrera’s extremists: a group of revolutionary soldiers from the borderlands who believe that the Republic left them in the hands of the enemy, a radical group that fights its own wars without regard for any central command but that still joined the main military force on the eve of the movement’s largest offensive, eventually becoming part of that movement. Even if it’s just an accidental parallel, it rings absolutely true because it’s been inspired by a pattern that has followed revolutions since the dawn of time.

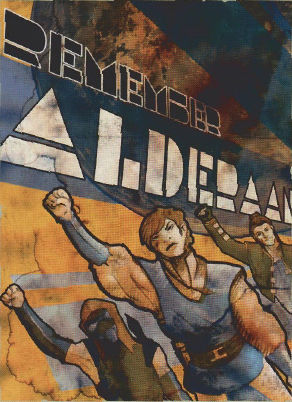

And of course, the introduction of such a realistic factor into the once-heavily-idealized Rebel Alliance completely changes the scenario. The existence of Saw’s extremists has actually changed the nature of the Rebel Alliance as we once knew it. The Legends universe had a figure that we could initially consider similar in Garm Bel Iblis, but his nature and Gerrera’s are very different: Garm was one of the founders of the Alliance and split from the organization due to differences with Mothma; Gerrera is something different, a nominal member of the Alliance that is at odds with its leaders and apparently still has to be talked into joining the offensive to steal the Death Star plans, but his path seems to be one of convergence. In the new canon the nature of the early Rebel Alliance appears to have been altered in a very profound way. Before the Battle of Yavin coalesces them, the Alliance doesn’t really look like a military organization, but more like a loose revolutionary movement formed by loyalists (Mothma and Organa), associated militias (the Lothal rebels) and radicals (Gerrera’s forces). We don’t know if there’s any equivalent to the Corellian Treaty, or if the Alliance pre-Yavin is looser than it used to be, but all hints point towards the latter. The Alliance, once unrealistic in its portrayal of white-clad nobles leading the harmonious forces of a united resistance front, is now as mired in conflict as its real-world counterparts were and still are.

And of course, the introduction of such a realistic factor into the once-heavily-idealized Rebel Alliance completely changes the scenario. The existence of Saw’s extremists has actually changed the nature of the Rebel Alliance as we once knew it. The Legends universe had a figure that we could initially consider similar in Garm Bel Iblis, but his nature and Gerrera’s are very different: Garm was one of the founders of the Alliance and split from the organization due to differences with Mothma; Gerrera is something different, a nominal member of the Alliance that is at odds with its leaders and apparently still has to be talked into joining the offensive to steal the Death Star plans, but his path seems to be one of convergence. In the new canon the nature of the early Rebel Alliance appears to have been altered in a very profound way. Before the Battle of Yavin coalesces them, the Alliance doesn’t really look like a military organization, but more like a loose revolutionary movement formed by loyalists (Mothma and Organa), associated militias (the Lothal rebels) and radicals (Gerrera’s forces). We don’t know if there’s any equivalent to the Corellian Treaty, or if the Alliance pre-Yavin is looser than it used to be, but all hints point towards the latter. The Alliance, once unrealistic in its portrayal of white-clad nobles leading the harmonious forces of a united resistance front, is now as mired in conflict as its real-world counterparts were and still are.

After all, Star Wars is a wonderful crucible of influences that manages to raise its head above what could be seen as mere pastiche. The spaghetti westerns of Sergio Leone, the samurai movies of Akira Kurosawa, the Michael Anderson heroics of fighter aces… all of them have their place in the Galaxy Far Far Away. But we should never forget that Star Wars also draws from the real world, from the history of war, of politics, and of conflict. That’s probably what makes it such a universal story. Despite the Force, despite hyperspace, despite cloning, the stories told are fundamentally human. Star Wars is at its best when it draws from history and, like the Jedi did ten years ago, Saw Gerrera seems more than ready to help us look again into what we can become when war is all we have.

Isn’t every war story fundamentally an anti-war story?

François Truffaut allegedly said exactly the opposite, that there is no such thing as an anti-war movie. According to this school of thought, even movies like Platoon or Paths of Glory or even Apocalypse Now end up glorifying armed conflict one way or the other, be it via showing war as a manly adventure, be it via focusing on honor and camaraderie between soldiers. See, for example, how the horribly abusive Sgt. Hartman from Full Metal Jacket has become a well-loved character, his frequent abuse often quoted without any hints of irony.

I don’t fully agree with this (maybe apocryphal) Truffaut quote, but I don’t think all war movies are necessarily anti-war, either. War is often portrayed as the ultimate adventure, as the vanquishing of evil, as the triumph of civilization against barbarism. There’s no anti-bellicism to be found there.

A truly anti-war war movie would leave people the way Requiem for a Dream leaves people thinking about drugs. It’s not impossible, but few would even want to try because it’s such a rough viewing experience.

Nice article. Saw Gerrera and his kind of rebels make sense during the early rebellion years. I can see later on Saw’s style of rebels becoming more unpopular and unnecessary as the Rebellion grows and becomes more organized as a military and governing body. But I like that they are adding this element to the early rebels, emphasizes the desperate times in the galaxy. And I’m really glad they got Whitaker for the role.

Think Saw has a copy of Che’s motorcycle diaries in his pocket? lol

Ha. I wouldn’t be surprised. I like to think of Cham Syndulla as a close equivalent to Che Guevara (I mean, even the names are painfully similar). Maybe he wrote “The Speederbike Diaries” about his youth travelling through Ryloth? Saw could have found a copy 😛

‘The Speederbike Diaries’ I like it, could make for a good comic series.

Great article David!