The Latin phrase mutatis mutandis loosely means “with only the necessary changes made” and that basically sums up the approach given to James Luceno’s characterization of the Galactic Empire in his novel, Tarkin. We won’t be reviewing the book per se – our editor has already done that – and we won’t be talking about the handling of Legends Expanded Universe material in this book (though mutatis mutandis also well describes it, especially given Luceno’s penchant for using EU) because ETE will be discussing the current EU/NEU state of play at a later date. Instead, we’ll take a look at the Galactic Empire and what Tarkin means for the Empire, especially next to portrayals in Edge of the Galaxy and A New Dawn.

So what’s the Empire like, in Tarkin? Truthfully, it’s the same as it always was. There are some changes to the ruling structure that we’ll get into, but the changes are essentially in name only and don’t materially change anything from the old EU structure of the Empire. There is some hinting that the anti-female and anti-alien policies are gone, but they’re not stated outright and it’s only really there by reading between the lines. What has changed is that the inconsistencies between the trilogies have been papered over – in the olden days we might have called them retcons, but the truth is that these changes are actually fairly minimal. Tarkin, like A New Dawn, presents an Empire that seems very consistent with the Legends EU in all but a few respects. This is a good thing – the Empire was generally very well characterized in the EU, at least structurally and philosophically. There were a few areas here and there that needed working, and the NEU has by and large taken care of those. The larger issues with the Empire had to do with the strength of villains as antagonists, which was sometimes flagging in the “Warlord of the Week” period of the EU: but whatever the weaknesses of the primary story in Tarkin, the man’s a good villain. But we’ll get to Tarkin the man a little later.

The Empire’s Peculiar Institutions

There are some people who are considerably bothered by the new sexually egalitarian Empire, whether because they don’t like seeing the Empire have positive social values or because they want to see the old EU upheld. There are also many who disagree, and think it’s about time that there were female Imperial officers, stormtroopers, and others who weren’t subject to odious discrimination. There are fewer still who think the same thing about the Empire’s anti-alienism, however. To many, this is a sine qua non of the Imperial system and is as integral to the Empire’s evil as the Jedi Purge or the destruction of Alderaan. But while the status of anti-alienism as official Imperial policy has changed, it’s not as big of a change as some might fear.

A friend of ours once wrote an excellent article on the EU’s handling of Imperial discrimination, slavery, and atrocities. He thoroughly documented the nature of Imperial sexism and anti-alienism and came to the conclusion that the examples of high-ranking females in the Empire led to an inconsistency that suggested discrimination against females was the result of the chauvinistic tendencies of individual leaders rather than Imperial policy, while the more limited examples of high-ranking aliens and consistent evidence of genocidal and slave-holding practices made anti-alienism a very official part of the Imperial régime. This pattern was generally true – Admiral Daala claimed that her promotion was rare and due to exceptional talent, but the presence of high-ranking females in supplemental material made her claims ring untrue. We’ve already written about how the use of sexism in the EU seemed more like an excuse not to use strong female characters, and we’ve received indications from authors such as John Jackson Miller and Jason Fry that Imperial sexism is a dead letter – what’s interesting is that Imperial anti-alienism has changed too, approaching the “unofficial discrimination” status that used to characterize Imperial misogyny in the old EU.

Under the EU, the Empire was anti-alien because Palpatine hated aliens – and secondarily, because he wished to exploit divisions in society to encourage his hold on power and to feed on hate. This approach was undermined by Palpatine’s consistent usage of alien underlings in the prequels, with the result that Mas Amedda becomes the highest ranking civilian official in the Empire in Tarkin (amusingly enough, the ci-devant Grand Vizier, Sate Pestage, was a notorious alien-hater). The Inquisitor in Rebels forms another prominent example of an alien Imperial in the new canon, and the trend seems clear enough. But Tarkin leaves avenues for traces of the old anti-alien Empire left over in people’s personal preferences. Tarkin himself is uncomfortable with aliens, and did not see many during his early days in the Outer Rim. The Core is more cosmopolitan – and while it may be a stretch to say that this means it is necessarily more tolerant, as there is plenty of discrimination in such places – and aliens are a far more common sight among its denizens.

With the prominent role Tarkin ends up assuming in the Empire, his policies become the face of the Empire to many people. He becomes an architect of a policy that outlives him, and as a result I think it’s fair to imagine that many aliens in the NEU were discriminated against and enslaved just like they were in the EU of yore. A lot of people took the change in the Empire’s anti-alien policies as whitewashing the Empire – but it’s not. If anything, there’s something to be said about a system that tacitly allows for such abuses to take place without any redress or correction. The Nazi metaphors of the Empire’s anti-alienism were an important part of the EU’s characterization of the Empire, but one so unquestionably evil that it allowed for very limited engagement with the subject matter. Anti-alienism that is not official, but widespread and overlooked can be addressed in manners that are far more interesting – but it remains to see if the EU will follow that approach.

The Emperor’s “Top Men”

While the Empire’s discrimination may have undergone some changes in the new continuity, Tarkin’s depiction of the Empire’s command structure features slighter changes. Here, we actually feel that fewer changes are better and thankfully the novel granted our wish.

When the EU became Legends, our biggest concern was that it would be a complete reboot of the EU and in particular, the EU’s portrayal of the Empire (or at least, the parts where it was actually done well). We thought it presaged an oversimplification of the Empire and heavy-handed references to contemporary politics instead of portraying the Empire using a mix of different historical influences. As we’ve discussed with sexism, oversimplification of evil reduces the Empire’s capacity as a villain: it’s a structure rather than just an individual, and as much as Sith Lords and stormtroopers may personify the Empire to many, making it a simple matter of evil wizards and faceless Nazis makes it hard for the Empire to become a really compelling evil. As we always try to remind people: the most sinister aspect of the Empire is that people bought into it. Like the fascists and Nazis, it was popular before it was hated: it is a seductive sort of evil, an evil created by the dark side of humanity rather than of the Force.

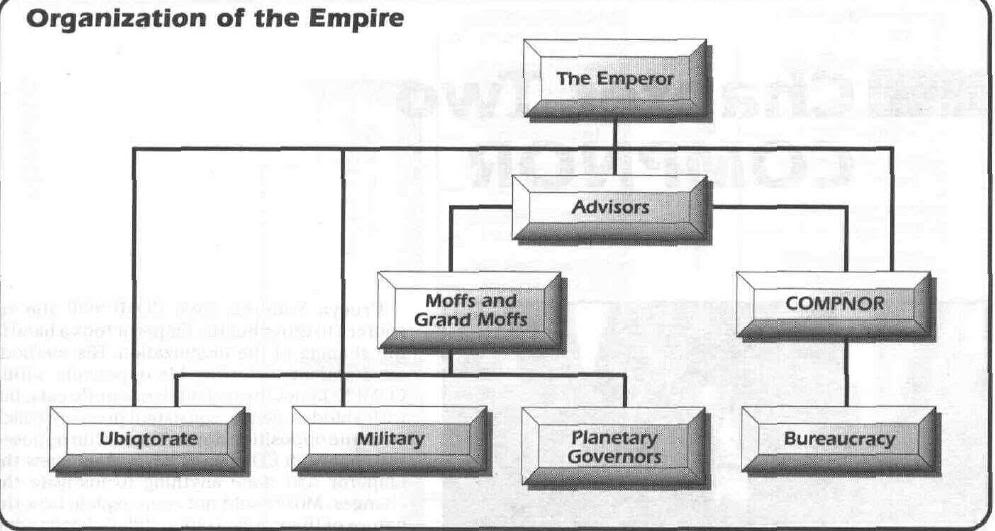

We won’t go on an extended discussion of the hierarchy of the Empire right now, since that could take its own article, but here’s one if you’re interested. The general idea is that it was complicated, both because the EU needed to account for changes between the films as well as inconsistencies in the novels. The EU had a handy explanation for it: the Emperor didn’t want anybody to have a secure power base and know exactly where they stood, that way people would be too busy playing power games against each other instead of trying to supplant him. Luceno’s novel captures the chaos and change in the Imperial command structure even though he’s no longer burdened by inconsistencies in the lore, but because he felt it best described the transition of the Empire from the Old Republic.

Tarkin’s Empire features the Emperor on top, while Vader’s next to him but with a somewhat unclear position vis-à-vis the formal hierarchy. The Imperial Advisors – some of whom form the Imperial Ruling Council – are the ones who actually run the show, since – like in the EU – the Emperor can’t be bothered with secular matters. The costumers who worked on Return of the Jedi drew inspiration from Catholic cardinals when they designed their elaborate vestments and miters, while the writers from West End Games described a Court that resembled the intrigues of the Chinese mandarins, Persian satraps, and Versailles all in one. In Tarkin, the Advisors – prominent among them Ars Dangor, an obscure RPG character whose importance we ceaselessly mentioned at TheForce.Net’s Literature forum especially in connection to his heretofore absence from Luceno’s intrigue-heavy novels – hold meetings with representatives of military intelligence, the “Joint Chiefs,” and others in order to decide on matters of policy. Military intelligence plays power games against the Imperial Security Bureau, while Tarkin himself – merely a Moff answerable to the Ruling Council – nevertheless implies that he knows things that not even Grand Vizier Amedda is necessarily privy to. These intrigues may bore some and excite others, but they remind us that the Empire is ultimately an institution driven by the lust for power: and that the individuals who sit in mirrored halls and polished drawing rooms are still as ruthless with lives as those who carry the guns.

As for those who do carry the guns, the military has its own complexities. The military chain of command as seen in the novel is still muddled and mixed, reflecting its origins in the Republic. By the end of the novel – and certainly by the time of A New Dawn, much later – things change. There are rivalries within the military as well, and a theme of Tarkin’s flashback scenes is his constant need to prove himself (a backwater lord, essentially) next to the proud aristocracy of the Core Worlds. He despises them and what they stand for – because his interests lie in efficiency and order – but also because they will never accept him as a peer. We could write a separate article on the man’s psyche and what influences him, but we’ll stick to his role in the Imperial hierarchy.

Tarkin begins the novel as one Moff among many, just like in the EU. Things change from there – under the EU, Tarkin was a Moff who was perhaps more charming and ruthless than the rest but one who didn’t really gain prominence until he invented the Tarkin Doctrine, at which point the indispensable Ars Dangor promoted him to Grand Moff. In Tarkin, we learn the Emperor has been interested in Tarkin from early on. They were friends when Palpatine was still a senator, and the Emperor has since kept his eye on him. He sees a sort of philosophical kinship in Tarkin, whose Rimward ruthlessness and efficiency appeal to him as an ethos for the Empire. The Emperor, Vader, and Tarkin are peas in a pod, we’re led to believe. This perhaps better explains the outsized influence Tarkin has (he is, after all, the villain of one of the three original films), but it still represents only one part of the Empire.

The Empire of Vader and Tarkin is not the Empire of the Core World nobility of the Imperial Advisors. But they are both the same Empire – and the tensions between them are what make the Empire so interesting to us. We see in the Empire both the colonial exploitation of the British Empire, the political remaking of the Roman Republic into an Empire, the intrigues of Versailles, etc. The Empire provides not only a rich set of adversaries, but also several different ideologies and philosophies for the protagonists to combat. A Han Solo might chafe against the formalities of the Imperial Court, but a Princess Leia would feel at home in them: yet both would still see Kren Blista-Vanee as a corrupt toadie of the Emperor. The Rebel Alliance consists of both rogues and nobles, and so the Imperial régime must have both its soldiers and its aristocrats. The struggle between the Rebels and the Imperials may well be one of good vs evil, but below that grand simplicity should lie complexity and nuance: that’s what makes this setting so interesting.

The Empire is still the Empire

Despite the breakdown of old certainties such as misogyny and anti-alienism in the Empire, the Empire in Tarkin and the new canon is still the Empire of old. Being less arbitrary about gender, race, or species doesn’t make the Empire less evil: it just allows the heroes of the novels to confront deeper issues and more difficult questions. It’s no longer the easy matter of overt discrimination. Tarkin doesn’t directly confront these issues. This is not necessarily a bad thing, since an evil protagonist requires the reader to come to his or her own conclusions, though a more compelling antagonist might’ve helped. Regardless, Tarkin sets the stage for future novels or TV episodes to handle the subject since it presents a Galactic Empire that is adjusted for a modern continuity and satisfyingly complex.