C’mon—for a split second there, you thought I was gonna talk about the movie Avatar, didn’t you?

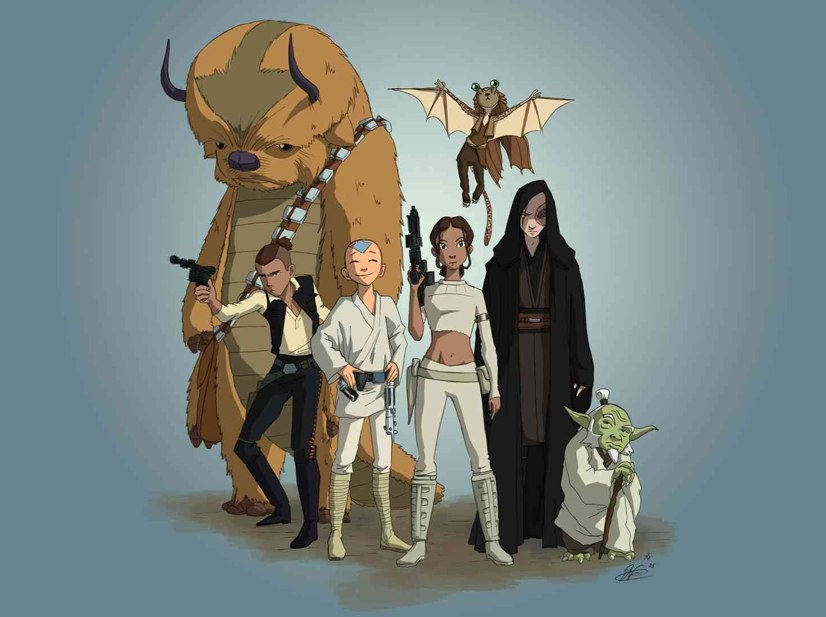

No, today is all about the other Avatar—the cartoon one, what with all the bending and such—and the lessons it could teach future (and current) Star Wars creators.

The Avatar franchise is primarily composed of two major Nickelodeon animated series—Avatar: The Last Airbender (henceforth ATLA) and The Legend of Korra (henceforth LoK). ATLA told the story of Aang, a long-forgotten magical totemic force who’s been frozen for one hundred years and wakes up to find the world he’s supposed to protect has moved on without him, and is now under the thumb of the expansionist Fire Nation.

“Magic” is a loose term here, because all supernatural abilities in this universe are rooted in one of four natural elements—earth, fire, water, and air. To “bend” an element is a learned skill rooted in one’s natural temperament, but each has been taken up as the banner of a different nation, and the practicing thereof has become strongly segregated. Once the Fire Nation has been, well, let’s just say dealt with, at the end of ATLA, LoK picks up years later, and tells the story of a new, and much different Avatar (the only being capable of mastering all four elements, who is eternally reincarnated much like the Dalai Lama) alongside the remnants of ATLA’s cast.

Of course, this Avatar spawned a movie, as well—but the less said about that, the better.

Lesson #1: White is not the default

When Lando Calrissian showed up in The Empire Strikes Back, people no doubt marveled at George Lucas’ bold storytelling choice—a black man, old friends with a white main character? And his race never even comes up? Such a thing was scarcely done in those days. Even still, if you go back and read the Marvel Star Wars comic series of the time, you’ll notice that while the authors just loved using Lando, very few of them bothered to make even one other human character, Rebel, Imperial, or scoundrel, a person of color. I mean, Lando was enough, right?

Things have certainly improved in the thirty years hence, but as followers of my ongoing diversity conversation at TheForce.net can tell you, not nearly as much as you’d think—for example, in the New Jedi Order novel series, a sprawling nineteen-book saga that rivals the Original Trilogy itself in scope, about one out of every three main characters is a straight, white, human man. And that’s in an entire galaxy of species!

Meanwhile, in Avatar, the presence of white people is so muted as to be entirely debatable. Aang himself can easily come across as white to the casual viewer, as can the bulk of the remaining airbenders we see (which, given the title, is not many). The same goes for members of the Fire Nation, including ATLA’s main antagonist Prince Zuko. Where this becomes tricky is in the two series’ heavily anime-inspired character design, and further, in their extremely Asian-inspired cultural design. I’m sure others could put this more elegantly than I can, but in the broadest possible strokes, airbenders are inspired by Tibetans, and firebenders are inspired by the Japanese—both groups whose skin tones could be mistaken for white in the absence of distinguishing features.

Meanwhile, in Avatar, the presence of white people is so muted as to be entirely debatable. Aang himself can easily come across as white to the casual viewer, as can the bulk of the remaining airbenders we see (which, given the title, is not many). The same goes for members of the Fire Nation, including ATLA’s main antagonist Prince Zuko. Where this becomes tricky is in the two series’ heavily anime-inspired character design, and further, in their extremely Asian-inspired cultural design. I’m sure others could put this more elegantly than I can, but in the broadest possible strokes, airbenders are inspired by Tibetans, and firebenders are inspired by the Japanese—both groups whose skin tones could be mistaken for white in the absence of distinguishing features.

In any event, all this is to say that the extent to which the light-skinned characters are “white” or “Asian” is open to the interpretation of the viewer. And meanwhile, the Earth and Water Kingdoms are largely (though not exclusively) composed of darker-skinned characters—the former inspired by “mainland” Chinese heritage and the latter by the Inuit and Eskimo peoples. As such, there’s something for everybody; not only are people of almost all colors accounted for (though I have to admit, you’d be hard-pressed to find a character who could pass for, say, Nigerian), but the world of Avatar is distinctly everybody’s—since each nation is a hodgepodge culture to some extent, it’s impossible to graft any larger statements about one real-life nation or another onto the narrative, and best of all, several of the protagonists—notably water tribe members Katara and Sokka, and later Korra herself—are such an ambiguous shade of brown that pretty much any race could claim them if they really wanted to.

Other big Avatar fans might disagree with me on this, but I don’t think the strength of the franchise’s inclusivity is its overwhelming Asian-ness, but rather its overwhelming everything-ness.

Lesson #2: Everybody can contribute

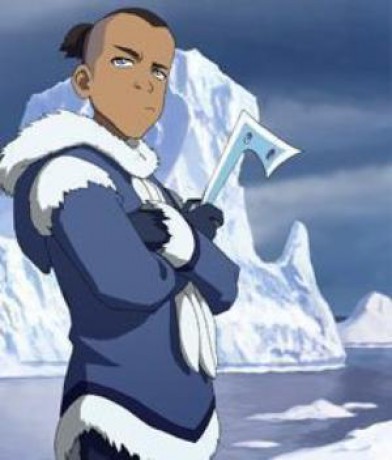

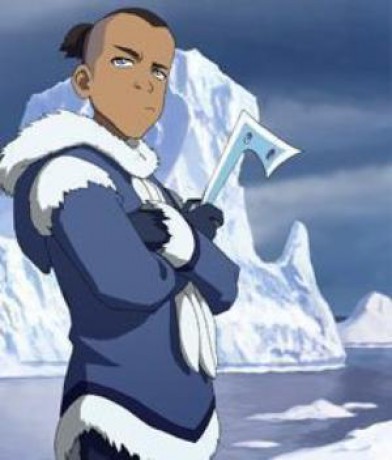

Of course, just because one is born into, say, the Water Tribe, doesn’t mean they’re a waterbender. My personal favorite character in the entire franchise is Sokka, brother to waterbender Katara and practitioner of the ancient and deadly art of…boomerang.

It’s never made totally clear why some people aren’t benders—this subject actually gets way more interesting in LoK, by which point the Fire and Earth Kingdoms have founded the wholly-integrated Republic City; where a firebender and an earthbender can and will have children of both types, or even nonbenders altogether.

It’s never made totally clear why some people aren’t benders—this subject actually gets way more interesting in LoK, by which point the Fire and Earth Kingdoms have founded the wholly-integrated Republic City; where a firebender and an earthbender can and will have children of both types, or even nonbenders altogether.

In Star Wars, two Jedi—or even one Jedi and a muggle—will almost always, like 98% of the time, give birth to Jedi children. Not only does this diminish the franchise’s “everybody can make a difference” message more and more with every birth, but it turns Force-users into some kind of bland, amorphous super-race.

Sokka, meanwhile, is with every breath the Han Solo of ATLA. No destiny is so epic, so spiritual relevation so profound, that Sokka won’t roll his eyes at it and wonder aloud when they’re getting something to eat.

But just like Han Solo, he’ll still buckle up in the end and launch himself into the cause of the week alongside his magical friends—and often he’ll even be the brains of the operation, as he’s only too happy to tell you. At first, LoK seemed poised to sidestep the nonbender type with its already-noteworthy introduction of Bolin and Mako, two brothers of two different bending types, but by the end of the first season they had given us Asami, Mako’s nonbending girlfriend, who held her own in battle thanks to another innovation of the LoK era—technological know-how.

Star Wars shouldn’t need to learn how to use the Han Solo character type; Star Wars invented it. But all too often—both in the prequels and in far more of the Expanded Universe than is excusable, it has proven itself willing to ignore the valuable lesson of the crafty smuggler.

Lesson #3: Don’t be afraid to move on

And speaking of Korra, if there’s one truly critical thing ATLA has over Star Wars, it’s that it knew when to quit. The original series knew the exact bounds of the story it wanted to tell from day one, and mercifully, the creators got the chance to complete that story without compromise or dilution. But once that story was over…the series ended.

And time passed.

And for a few years, there was nothing. But when ATLA’s popularity finally gave them a chance to continue the story, they didn’t give us a half-hearted Continuing Adventures of Aang and Friends—they jumped seventy years ahead.

Given that the Avatar, the magical pivot around which this universe turns, has to die for a new one to appear, they wisely realized that Aang’s story was done. And while he no doubt had many years of continuing adventures ahead of him, they were beside the point; to squeeze another conflict anywhere near ATLA’s level of import into Aang’s life would at best be a retread with an older and wearier cast of characters, and at worst, would be downright mean.

So they jumped, and jumped far. Aang has grandchildren now, and only a few of his generation remain. But not only does that give us a new Avatar in the kickass waterbending woman of color Korra, but it also provides a totally new context in which to tell a story—while still far-flung, the nations have begun to merge, and that merging has given way to astounding leaps in technology. While the world of ATLA could have been plucked wholesale from the middle ages, by LoK things have jumped straight through to the Industrial Revolution—which also carries with it a handy message about integration, if you ask me.

Story-wise, Korra’s problems are out of Aang’s wildest dreams—major-league sports competitions, killer mechs (no, really), and an antagonist leading an anti-bender revolution (remember #2?). The second season premieres in a couple weeks, and while the first season was pretty self-contained by design and largely resolved its story, I have no doubt that where they’re going from here will be totally unheard-of.

As for Star Wars, well…we’ve got Episode VII. People may roll their eyes at EU fans once we find out that Force lightning made Luke sterile and Han and Leia’s kids are named Steve and Linda, but the fact is, when it comes to the time period following Return of the Jedi, we’ve seen it all—reborn Palpatine, rogue warlords, Sith armies, extragalactic invaders? Done, done, done and done. As excited as I am at the prospect of spinoff movies about Rogue Squadron and young Han Solo and the Knights of the Old Republic, I have a hard time meeting Episode VII with anything more than muted apprehension—not because it’ll erase the EU, but because I’ve seen it all before.

But then, maybe they’ll take a page from Avatar and surprise me.

Meanwhile, in Avatar, the presence of white people is so muted as to be entirely debatable. Aang himself can easily come across as white to the casual viewer, as can the bulk of the remaining airbenders we see (which, given the title, is not many). The same goes for members of the Fire Nation, including ATLA’s main antagonist Prince Zuko. Where this becomes tricky is in the two series’ heavily anime-inspired character design, and further, in their extremely Asian-inspired cultural design. I’m sure others could put this more elegantly than I can, but in the broadest possible strokes, airbenders are inspired by Tibetans, and firebenders are inspired by the Japanese—both groups whose skin tones could be mistaken for white in the absence of distinguishing features.

Meanwhile, in Avatar, the presence of white people is so muted as to be entirely debatable. Aang himself can easily come across as white to the casual viewer, as can the bulk of the remaining airbenders we see (which, given the title, is not many). The same goes for members of the Fire Nation, including ATLA’s main antagonist Prince Zuko. Where this becomes tricky is in the two series’ heavily anime-inspired character design, and further, in their extremely Asian-inspired cultural design. I’m sure others could put this more elegantly than I can, but in the broadest possible strokes, airbenders are inspired by Tibetans, and firebenders are inspired by the Japanese—both groups whose skin tones could be mistaken for white in the absence of distinguishing features. It’s never made totally clear why some people aren’t benders—this subject actually gets way more interesting in LoK, by which point the Fire and Earth Kingdoms have founded the wholly-integrated Republic City; where a firebender and an earthbender can and will have children of both types, or even nonbenders altogether.

It’s never made totally clear why some people aren’t benders—this subject actually gets way more interesting in LoK, by which point the Fire and Earth Kingdoms have founded the wholly-integrated Republic City; where a firebender and an earthbender can and will have children of both types, or even nonbenders altogether.

Star Wars is no stranger to “genre” storytelling, and John Jackson Miller’s Kenobi,

Star Wars is no stranger to “genre” storytelling, and John Jackson Miller’s Kenobi,