The introduction of this piece is spoiler-free. If you don’t want details of Alphabet Squadron a warning will let you know when to stop.

We think we’ve seen this story before. But we haven’t.

There are certain types of stories in Star Wars that seem to recur again and again. Stories of Imperial defectors joining the Rebellion / New Republic tend to be among the most common of them. Even since the continuity reboot of 2014, we’ve seen stories of defectors more than once. Zare Leonis, Thane Kyrell, Sinjir Rath Velus, Alexandr Kallus, and Iden Versio were all Imperial defectors. It’s a type of story we know well: a character believes in the Empire and its mission, comes to a realization or crisis of conscience (often during an atrocity), and joins the good guys with their past seemingly forgotten and behind them. The stories play out a bit differently each time and the specific details vary — but the broad strokes are the same.

Those small differences do matter. In a galaxy-wide Empire, we would figure (or hope) that it’s a common thing for people in the Emperor’s service to recognize the error of their ways and defect. The details affect how the story is told, and even why it’s told. Famously, Battlefront II’s promotional materials led us to believe that Iden Versio and her Inferno Squad were helping to establish the die-hard First Order. When the predecessor novel Inferno Squad underscored the idea that Iden and her group were Imperial loyalists, we were surprised that Battlefront II would end up being a story about defection from the Empire. Rather than being “gotcha” subversion for the sake of a twist, it invited the reader to look again at the novel and look at the seeds that had been planted; it turned out that the story was less about defection and more about the whys and the hows and the what-nexts of defection.

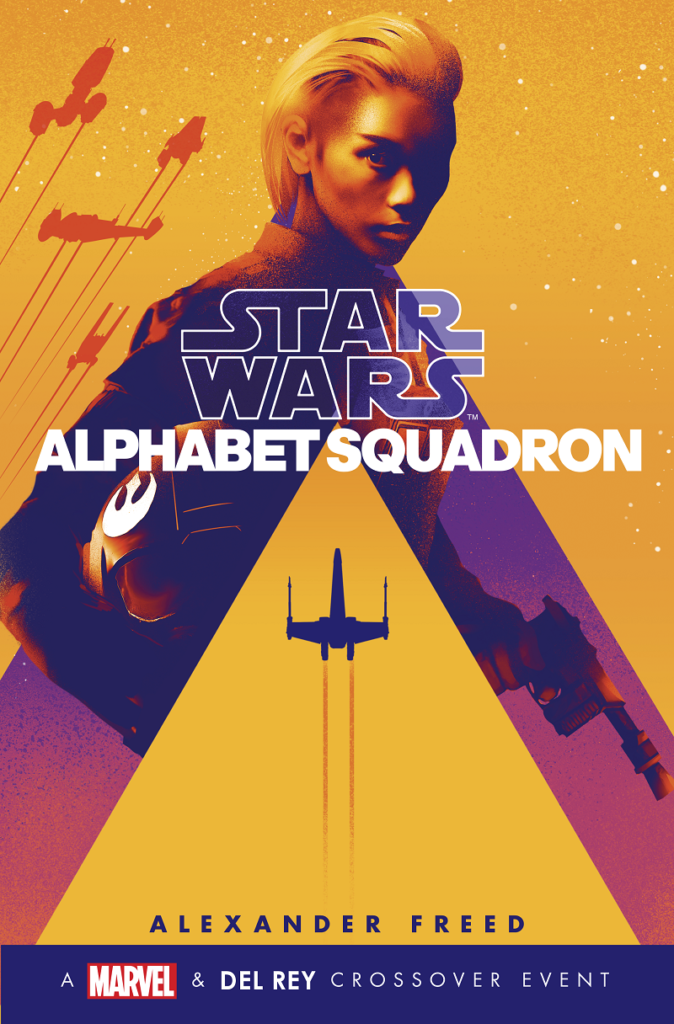

Alexander Freed’s Alphabet Squadron examines all of this — the ideas and expectations we have for Imperial defectors and the idea of subversion of expectations less for its own sake and more for telling a more interesting story. Beyond that, Freed does what Freed does best — he grounds the story in reality and causes painful realizations through the characters’ emotional journeys. Sure, defection is common — but what does that mean in a post-Endor, post-Operation Cinder galaxy where the Empire really has outstayed its welcome? And just how trusted would an Imperial defector be by those who the Empire has harmed not just once, but many times? Is there such a thing as too little, too late?

Former Imperial pilot Yrica Quell is our window into all of this — we see things from her perspective, and from outside her perspective. She’s the leader of a fighter group, but she’s not the unifying squad leader that we’re used to in pilot stories. She holds herself apart — both because of her past and because of her actions, and that what makes her interesting. Alphabet Squadron is a story about many things — but I want to dig most deeply into Yrica Quell and the topic of Imperial defectors.

Article will contain spoilers after this point! If you have not yet finished the novel and do not wish to be spoiled, come back to the rest of the article later!

Read More