Mandalorian culture has been a rather interesting topic of discussion for quite a while now, pretty much since Boba Fett first walked onto people’s screens, and the idea was seeded that he came from a culture of warriors dressed in similar armor. It’s been teased, fleshed out, then rolled back and retconned and fleshed out again several times, from the pre-prequel era in Boba’s early Expanded Universe exploits, through the prequels with Jango Fett’s backstory and Karen Traviss’s books, then in The Clone Wars, and now in Rebels.

Back in TCW, most of the slate was wiped clean, with the idea that Mandalore had been taken over by a largely pacifistic faction and their warrior culture was frowned upon and shunned. The few warriors who stuck around were labeled terrorists, siding with the Death Watch. Then Obi-Wan got involved, Darth Maul arrived, and things started to go downhill very quickly. By the end of what we’ve seen (with the fabled “Siege of Mandalore” being largely unknown) Mandalore has been torn to shreds by civil war, with Duchess Satine and her faction being all but wiped out and two factions of the Death Watch battling for control of the capital.

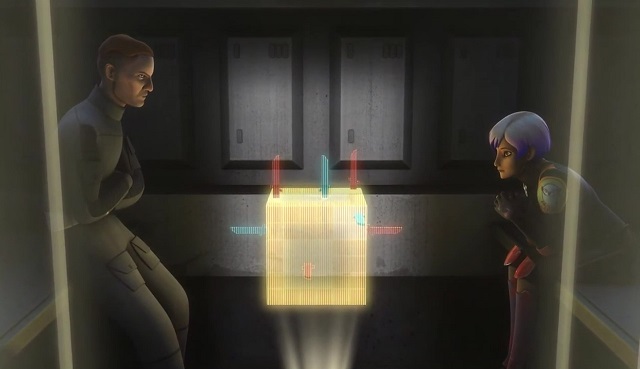

Since then, Rebels has been trickling out the details about what Mandalore is like in bits and pieces. Sabine mentioned in the first season that she had attended the Imperial Academy there, and in the second season we were introduced to Fenn Rau and his Protectors, a faction of soldiers acting as police of a hyperspace lane. They value honor, respect the strong, and strike an alliance with the Rebels while still nominally serving the Empire in an attempt to maintain their independence from either faction. We also got our first clues of exactly who Sabine Wren is, in that her family is said to be loyal to clan Vizsla, the same clan as the leaders of the Death Watch. Read More

![Star-Wars-Propaganda-Poster-Set_Page_06[1]](http://eleven-thirtyeight.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Star-Wars-Propaganda-Poster-Set_Page_061-337x450.jpg) Today we conclude our week of Star Wars Propaganda coverage with the second part of our interview with author Pablo Hidalgo. This piece is a continuation of

Today we conclude our week of Star Wars Propaganda coverage with the second part of our interview with author Pablo Hidalgo. This piece is a continuation of ![Star-Wars-Propaganda-Poster-Set_Page_05[1]](http://eleven-thirtyeight.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Star-Wars-Propaganda-Poster-Set_Page_051-338x450.jpg) On Wednesday, I

On Wednesday, I ![Star_Wars_Propaganda_New_Cover[1]](http://eleven-thirtyeight.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Star_Wars_Propaganda_New_Cover1-337x450.jpg) (Programming note: this piece is the first of three about Star Wars Propaganda. On Friday and next Monday, I’ll be posting a two-part interview with the author, Pablo Hidalgo.)

(Programming note: this piece is the first of three about Star Wars Propaganda. On Friday and next Monday, I’ll be posting a two-part interview with the author, Pablo Hidalgo.)