I’m going to do this round a tiny bit differently—while question 9 was indeed directly submitted to me for this series (by my co-worker Peter Zappas), question 8 is more about addressing what I see as a common misconception. Both relate, either directly or indirectly, to topics that will be (or at least appear to be) raised by the forthcoming Star Wars Rebels TV series, so I thought it would be handy to pair them up in one shot.

8. Why would the Inquisitor in Rebels be an alien if the Empire is xenophobic?

This is something that comes up every so often when someone like Thrawn, or Mas Amedda, or the Pau’an Inquisitor previewed a few weeks back, is shown to be flourishing, or even vital, within Palpatine’s Empire.

While I’ll admit it’s not quite as black and white as I’d like it to be, the fact is there’s no direct evidence whatsoever that Palpatine himself had any anti-alien bias, and a lot of circumstantial evidence to suggest that he didn’t.

Ultimately, Palpatine was a Sith Lord first, a politician second. When one seriously examines his plans and worldviews as related in the books and reference material, you get the distinct impression that Palpatine viewed essentially all living beings as slaves waiting to happen. Per the last volume of The EU Explains, Palpatine’s endgame was to personally rule the galaxy for eternity, and his efforts to stamp out free will and individual autonomy and initiative were a big part of the reason that things fell apart so completely after he died. To suggest that he had special animus for nonhumans, then, is to believe that humans would’ve been in any way better off in his ideal society—when in reality all beings would have been equal in their total subservience and submission to his will.

So why the clear anti-alien bias in the Empire? Well, humans were by a wide margin the dominant race in the galaxy, and exploiting their baser prejudices was a convenient means to an end. Palpatine’s slew of nonhuman attendants in the prequels demonstrates that even if he did find other species distasteful on some level, he was perfectly happy to use them when handy—and in the case of Mas Amedda, even bring them into the fold regarding his true plans for the galaxy.

Palpatine’s real genius, after all, was in using whatever materials were available to his maximum advantage. On one side he had entrenched and influential human families in the Core like the Tarkins and the Tagges, and on the other he had overgrown corporate powers like the Trade Federation and the Techno Union, all owned and populated by aliens. The former were only too happy to help him bring the latter under heel on the assumption that that was all he really wanted—which, of course, was far from the truth.

And then there’s the Inquisitor. The Inquisitorius was conceived as something like Palpatine’s NSA; their existence was known, but their operational details—hunting down the remaining Jedi—were in the dark to almost everybody. If a Pau’an Inquisitor was forced to interact with some bigoted Admiral or Moff during the course of a mission, there’s half a chance he’d have done so without even revealing his status as an Imperial agent. And even if knowledge of a Pau’an Inquisitor somehow got into the hands of an Imperial highly-placed enough to cause Palpatine some degree of embarrassment (though that’s a vanishingly small list, especially by the time period of Rebels), like with the NSA, he’d still have plausible deniability—“Pau’an? What Pau’an? I would never!”

Further Reading: Darth Plagueis, The Dark Lord Trilogy, The Dark Empire Sourcebook

9. Are the stormtroopers in the Original Trilogy still Jango clones, or a mix of clones and recruits?

Well, for one, when the Original Trilogy was coming out, it didn’t really occur to anyone that stormtroopers might have been clones. While evidence can be found if one wants to find it (“a little short for a stormtrooper”, after all, implies a certain biological uniformity), and, hilariously, a low-rent magazine called the Star Wars Poster Monthly published an article about that very subject around the time of A New Hope‘s release, no one officially knew about it. The Marvel comics of the time even had a handful of one-off stormtrooper characters with distinct names and personalities, on the assumption that they were normal recruits similar to those seen in the Rebellion.

This assumption carried on into the “modern” EU of the nineties, with the notable exception of the Thrawn Trilogy—which addressed the subject of clone armies head-on, while not quite lining up with the picture painted by the prequels. Clone soldiers in those books were distinctly not run-of-the-mill stormtroopers; they had different Force presences from regular people, and were largely blank mental slates, if not outright unstable.

Once Attack of the Clones introduced the Grand Army of the Republic, the EU began making slow, deliberate steps toward reconciling the recruit idea (to say nothing of that “Academy” Luke was so keen on joining) with the strong implication that these were the people who eventually became stormtroopers.

For starters, you have to keep in mind the Jango clones’ accelerated aging—by Revenge of the Sith, the original batch was biologically twenty-six; by ANH, they’d have been sixty-four. Hardly fighting trim, right? AotC mentions the Kaminoans keeping Jango around, because they needed fresh samples in order to keep producing high-quality clones; once Jango died at Geonosis, that ship had sailed. So even assuming they started a fresh batch right before the Clone Wars broke out, those clones still would’ve been forty-four by ANH, and probably not fit for the front lines. That’s not to say these guys didn’t stick around (official word is that about a third of the stormtrooper corps were Fetts as of ANH), but it’s likely that they took on more and more leadership roles at time went on—or at least training positions, in the likely event of anti-clone prejudice.

Where Rebels may play into this topic is the possibility of including A) regular recruits, and B) other clone templates. Offhand statements from George Lucas suggest that in his view, once the war was over and the clones were needed less for active combat and more for general peacekeeping, the process of selecting clone templates became politicized, with individuals being selected less for their aptitude and more for knowing the right people. The EU has gotten into this a little bit, but only in the immediate aftermath of RotS, so what exactly things were like fourteen years later (when the show starts) is hard to say. What we can say is that this circumstance, combined with the decreasing effectiveness of the Jango clones and the introduction of the first genuine recuits to the stormtrooper ranks, serves to make the overall lousiness of the Original Trilogy stormies a lot more understandable.

Further reading: Order 66, In His Image, When the Desert Wind Turns: The Stormtrooper’s Tale, the Thrawn Trilogy

Palpatine was and how thrilled they should all be that Hethrir is bringing evil back. The twins aren’t buying it, of course, and soon enough they lead an exodus with the help of a friendly dragon (no, really).

Palpatine was and how thrilled they should all be that Hethrir is bringing evil back. The twins aren’t buying it, of course, and soon enough they lead an exodus with the help of a friendly dragon (no, really). The year was 1995.

The year was 1995.

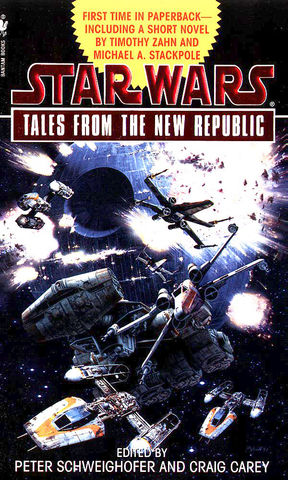

thus, New Republic ended up being their first and only printing after all. Darkknell, of course, was a follow-up to Stackpole and Zahn’s Side Trip, which was published in both the Adventure Journal and Tales from the Empire, so it remains possible that it too was simply a leftover rather than a piece specifically meant for the collection; again, I couldn’t say.

thus, New Republic ended up being their first and only printing after all. Darkknell, of course, was a follow-up to Stackpole and Zahn’s Side Trip, which was published in both the Adventure Journal and Tales from the Empire, so it remains possible that it too was simply a leftover rather than a piece specifically meant for the collection; again, I couldn’t say. Meanwhile, if there was one question I heard people ask Del Rey in those early days more often than “when are you doing more anthologies?”, it was “when are you doing more X-Wing books?” And sure enough, last year we got Aaron Allston’s Mercy Kill.

Meanwhile, if there was one question I heard people ask Del Rey in those early days more often than “when are you doing more anthologies?”, it was “when are you doing more X-Wing books?” And sure enough, last year we got Aaron Allston’s Mercy Kill.