“When you’re directing a scene on the Millennium Falcon, it doesn’t make the scene good. Now it’s bitchin’ that it’s on the Millennium Falcon. You want a scene on the Millennium—if I could make a suggestion, direct scenes on the Millennium Falcon, cause it’s hugely helpful. But it doesn’t make the scene automatically good.”

–JJ Abrams at San Diego Comic-Con, July 2015

One of the major recurring topics of Star Wars fandom over the last few years has been the notion that this is, in some fundamental way, a movie franchise. At face value that may seem obvious, but there’s more to it than there might seem right away. For a lot of fans, especially nineties kids like myself, far more of our formative years was spent reading Star Wars books, comics, Essential Guides, and so on than watching the films. Even once the prequel trilogy was coming out, and causing occasional headaches for the Expanded Universe, there was always an understanding that the film aspect of the franchise was not just finite but distinctly limited—they were a storm we just had to weather before the EU took over again. Just like there was never going to be an Episode VII, nor would there be a III.V, or a Zero, or a Negative Twenty. The films were Anakin’s life story, and if that wasn’t the major draw for you, no big deal. If you liked harder military science fiction, Star Wars was a novel franchise about the continuing war with the Empire. If you liked Jedi melodrama, the comics of John Ostrander and Jan Duursema were your Star Wars. If you were a gamer, Star Wars was Dark Forces or X-Wing Alliance or The Force Unleashed.

And yeah, one of the coolest things about it was that all those different pocket universes intersected and fed off of each other—at least in theory—so even if you mostly kept in one or two lanes yourself you still got to feel like part of this grand tapestry of SW fandom. Things are different now, and frankly I don’t blame some people for still not being okay with that, but it is what it is. Movies are once again steering the ship, and will be for the foreseeable future no matter what part of the timeline you’re into; that doesn’t ruin Star Wars, in my opinion, but it does necessitate a degree of realignment. What role should supplemental material—which is what the books are now, supplements—play in a movies-first franchise? What role can they play best? Read More

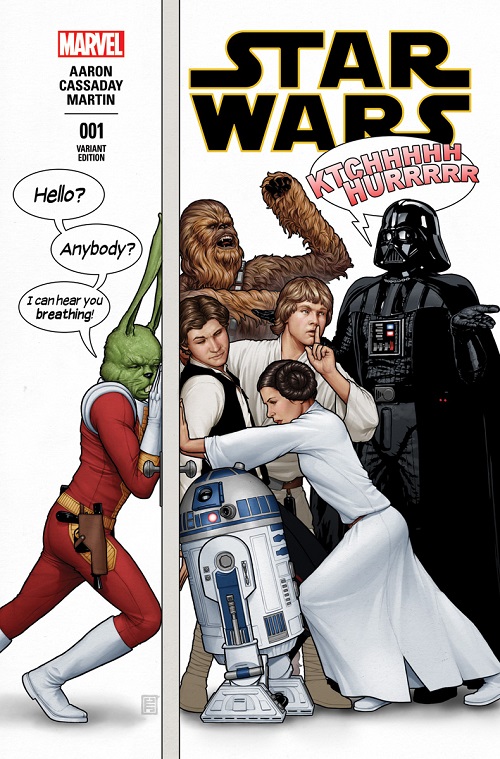

Mike: When I was first acquainting myself with the Star Wars franchise in the late nineties, the volume of Expanded Universe material I felt it necessary to catch up on was already quite daunting—most of a decade’s worth of novels and comics were already out there, and more were arriving all the time. Luckily, one huge batch of content was pretty widely regarded as not worth my time: the original 107-issue Marvel Star Wars comic series. Having run from 1977 to 1986, it was more than a decade out of print by the time I laid eyes on A New Hope, and to say the stories had fallen out of fashion during the peak of the Bantam era would be an understatement. So for a long time, I didn’t see a reason to go anywhere near them.

Mike: When I was first acquainting myself with the Star Wars franchise in the late nineties, the volume of Expanded Universe material I felt it necessary to catch up on was already quite daunting—most of a decade’s worth of novels and comics were already out there, and more were arriving all the time. Luckily, one huge batch of content was pretty widely regarded as not worth my time: the original 107-issue Marvel Star Wars comic series. Having run from 1977 to 1986, it was more than a decade out of print by the time I laid eyes on A New Hope, and to say the stories had fallen out of fashion during the peak of the Bantam era would be an understatement. So for a long time, I didn’t see a reason to go anywhere near them.